Study for Roger

, 2012

Did I mention that I made a big pixelated Predator drone for the New Aesthetic panel at SXSW, this year? It pretty much defined the first three days I was in Austin since it's all I thought about and there wasn't a single moment during that time when the whole thing wasn't about to go completely off the rails.

The morning after we arrived I took a cab out to North Austin to visit the nice people at Polyplastics with whom I'd been having long conversations about foam for, by then, three weeks. Bill and everyone else there were insanely helpful and always accomodating of my endless chicken-and-egg questions. Since we didn't really know what was even possible it was often hard to know we were even asking for.

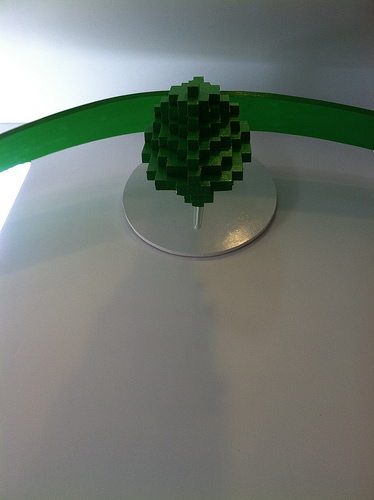

This is where Roger was born:

A little while later I stood by the side of the road in the rain, waiting for the number 3 bus to take me back to the house, with a stack of eight five t by 1 by 12 sheets of MC3800; MC3800 is apparently used as the padding in rear car bumpers. And then spent the next three days assembling a big and goofy pixeldrone

out of foam, bourbon and a small orchestra of inappropriate tools.

None of the lines are as clean as I'd like and there's a gaping seam in the head which tells you where I managed to get my measurements all wrong. And it's floppy. Really floppy. I have a whole new appreciation for people who design airplanes and why everyone is so panty and excited about laser cutters.

But it was worth doing if only to walk it down the stairs of the Driskil Hotel afterwards, with all its balloons riding high, in to the lobby and through the breakfast crowd out in to the street. And then, yeah, we went swimming with it.

The next day I cut it in half and stuck the head and the wings in a big green bag and took it home with me on the plane. And then what? What do you do with something like a 5 by 10 t pixeldrone? Maybe I should have consulted with Myles first but, in the end, I mounted the head and covered the whole thing with green chroma key paint.

Then I named it Roger

and stuck it to the wall.

Why drones? Again, this is really all I'm going to say about it for the time being.

Why green screen? I'm going to punt on that, for now, and just point you to the end of a talk I did at Museums and the Web last April. Beyond that I've been more concerned with simply getting Roger dressed, so to speak, than I have with working out anything like a coherent reason why for anyone but myself. It seemed like a good idea. We'll see if it ages well.

And Roger

was just a lucky gift that life presented to me the other day.

So, there it is. Having already once covered it in papier mache and then painted it only to tear it all off the next day, I may still paint it once more to remove the spray gloss I applied yesterday. First I think I'll just live with it for a few days... and then re-paint it. Like I said, it's a study

.

The gloss cuts my eyes everytime I look at it now but, honestly, I need to step the fuck away from this thing for a little while.

I'm don't know if this is art

or just me putting a bow around a thing I did and making an extravagant prop for dinner conversations. I say it's a study because the uneven lines and the duct tape holding the wings together (that's where I had to cut them open to pull out the wooden doweling rods that had snapped off and gotten stuck inside...) are just proof of what happened and not necessarily what I had in mind. I will probably do this again.

Now, though, it is a captial-T thing with history

because it was present in the room when we did the panel.

I'm not really too fussed about it but it does raise an interesting question: Whether I am simply telling you about the work or actually showing it. Since this is the only place most of you reading this blog post would ever see it, anyway, does it really matter whether or not it's in the public meatspace? I'd probably still say yes

if forced to choose (if only because I'd like to kick Joseph Beuys in the teeth) but that doesn't mean the ground isn't shifting. We may not have jetpacks but we're not short on the constant need for adjusting our expectations.

If anyone is interested in actually putting it on display somewhere drop me a line since that would be fun, I think. Maybe I will start a Kickstarter project to build the thing for real: Proper big with hard lines and sharp edges and electric green car paint that makes you play porno music in your head. That would also be fun.

wanderdrone

A few weeks ago I went over to Ben's place for dinner. Often when you visit Ben you'll find his laptop plugged in to a projector and spraying the far wall with the idle wandering of Google Earth. It's a lovely display and that night we spent quite a lot of time first in the mountain ranges of Pakistan and then the province-sized industrial parks of China. The trick is to very gently flick your fingers to spin

the globe

in a way that it builds up enough momentum to keep moving without going so fast that nothing registers.

I had no idea until that night that the federal authorities in China are mandating that certain factories paint their roofs a specific shade of blue so that they can be read

from space by satellites. It makes perfect sense but is still all kinds of wacky and sort of makes you appreciate everything Mike Kuniavsky and crew have been beating on about with their BlinkMs that much more. I suspect, in the long-term though, just giving someone a paint roller and minimum wage is probably a more secure strategy when you stop and think about the bad craziness you could get up to by hacking a smart

roof and spoon-feeding crap to the space robots...

It's also all a nice reminder of just how big the Earth is. We are so used to airplanes and the Internet and other magic port-holes through geography that it's easy to neglect the scale of it all.

Someone asked whether it was possible to do the same momentum trick with the iPad version of Google Earth but it's not. Honestly, if the iPad version of Google Earth had momentum

none of what's about to follow would have happened.

Ever since that evening I've been thinking about building a plain-vanilla tiled/slippy wandermap

of my own. Nothing fancy, just a simple thing that was native to the web and could work on all these extra screens we're collecting as time goes by. For some definition of works

the thing I've made will run, albeit slowly, on my Kindle's web browser which has become a good sort of baseline for web applications.

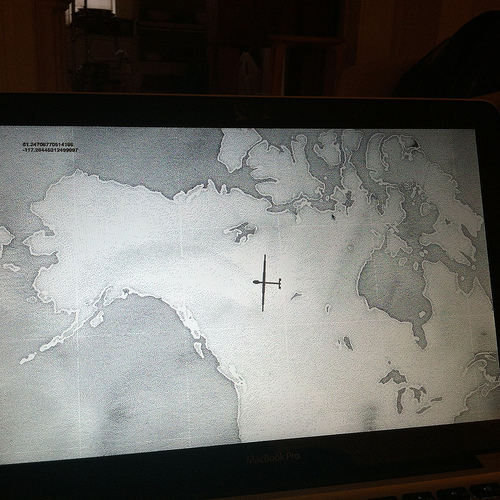

Here's an early version using the dithered

satellite tiles you may know and love from things like the woedb and building=yes.

It really doesn't do very much. It wanders around. In a straight line. In one of eight directions. Every once in a while it picks a new direction. Occcassionally it zooms in or out of the map. But it's a lovely way to browse a map, almost like we used to when atlases were rare and special and we would linger over them just for the pure joy of investigating a place and slowly breathing it in.

The wandermap will work with any tiled map source but for now I'm enjoying a (water)dithered version of Stamen's new watercolor maps. It might seem a little perverse to strip all those colours out the source imagery but long before we became enamoured with pixelation we fell in love with half-tones for all the same reasons.

And then I put a bird on it.

Both the wandermap and the wanderdrone

owe a debt of imagination (and a few drinks) to James Bridle's A Ship Adrift and the more recent shadow drones (made with Einar Sneve Martinussen) as well as Michal Migurski's work on the Mondo Window website last year. It would be lovely to do wandermap in the style of the three-quarter bird's eye Mondo Window maps but since this was a late-night weekend project I decided to do the dumb and simple version first.

I'm not going to go over the thing with the drones again since I think I mostly covered that in the #sxaesthetic talk.

Every problem is met using the poor man's solution because I am that special combination of too stupid or too lazy to bother with the Real Math necessary to make it elegant. It's a bit clunky in places (and sometimes the tiles are missing or left in the render-mines on a first fly-over) but basically it works and there is time enough to dig in to the code that Tom MacWright's been writing for Easey and Tom Carden did to make Airport City fly

after the current version has been left to bake in the sun for a while.

Speaking of Airport City if you look carefully at the code (for the wanderdrone) you'll see that there are hooks for pairing the waterdithered tiles with road and aeroway tiles from the first project. It looks great in places but it sort of spotty overall so it's been disabled for now and I may use this as the excuse to revisit that thread again.

Anyway, here is the wanderdrone. It wanders around. Looking for Myles.

http://www.aaronland.info/wanderdrone/

Speaking of dithering, I finally got around to bundling up all the code that generates those tiles as a proper Tilestache provider. It lives on Github in the tilestache-atkinstache repository. Soon, I will tweak the code so that it can generate tiles with transparent backgrounds.

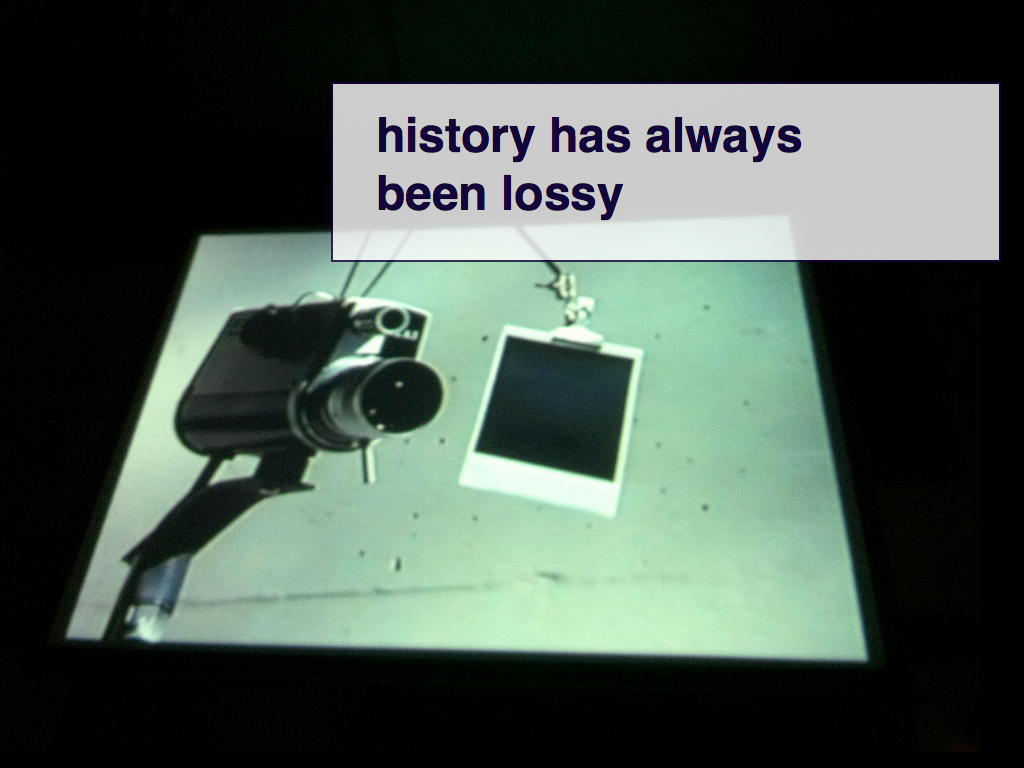

The New Aesthetic

I had the pleasure and the privilege of participating in James Bridle's panel about the New Aesthetic at this year's South By South West conference, alongside Joanne McNeil, Ben Terrett and the un-fucking-stoppable Russell Davies. They've all written up their talks which I've added below including James' closing commentary.

I spent the first three days of the conference making a drone. Out of foam. And then I said this or at least tried to. I got a little flustered in the rush of it all and dropped a few things on the floor. Bruce Sterling said some nice things about the panel afterwards. That was lovely.

The opening of Thomas Pynchon's "Gravity's Rainbow" is set in London at the end of World War 2. It is during the time just after Germany had deployed its new supersonic missile, the V2, and was targeting it at the British capitol.

Traveling faster than the speed of sound, Londoners only heard the whistle of the missile if they were lucky enough to survive the initial blast. Everyone is understandably creeped out not knowing, in Pynchon's words "what may come out of the sky".

During the seige of Stalingrad the Russians made a point of not letting the Germans sleep, causing them to be constantly on edge and hyper-aware of everything.

In the novel this inability of those people, trapped in London, to reconcile the advent of a technology whose consequences have no recourse (that's a fancy way of saying: you're dead) with its complete lack of presence or warning signs begins to take on a life of its own. At least with long range rifles and snipers there was the crack of the shot, even if there was no chance of escape.

One character is sent out to map the blast areas and ends up using the exercise as an opportunity to map attractive women while his co-workers imagine that the map must contain some pattern, almost religious in its meaning, through which they might find an understanding of a sky turned so angry.

Gravity's Rainbow is historical fiction, a big plushy bear of a story wrapped around the skeleton of historical fact.

Sixty-seven years later it is a not inaccurate way to describe to circumstances of those people who live day to day with the threat of modern unmanned drones.

If you think this pixelated foam replica of a drone is weird and goofy you should know that James and I spent a good amount of time investigating what it would take to have a lifesize inflatable balloon replica of a Predator drone made. Like the kind of thing you'd see in the Macy's Day parade.

It's not very expensive. You can have one made for about 6,000 dollars. 8,000 dollars if you want it made with shiny, reflective material. And about 1200 cubic feet of helium to float the thing. As you can see we didn't end up having it made. For a few reasons:

First of all the only way that we'd be able to fit it in this room, with its 60 t wingspan, would be sideways which always seemed a bit ass-y just on aesthetic grounds.

Second, there was some question whether the ceilings were high enough for a giant balloon and whether or not it would go crashing in to all these nice chandeliers.

A lifesize balloon drone, though, remains a hard idea to let go off once you've decided it's worth doing.

I love the idea of walking around SXSW trailing a balloon drone in tow, like walking a friendly and sort of clumsy Great Dane, but anything that big and with that much surface area on which to "catch wind" is going to require a small army of people to keep the thing from floating away or crashing into buildings.

And even if we had those people at our disposal I am not really confident that the thing would fit down many of Austin's streets. The city probably has rules about these kinds of things, whether or not they let the town fill up with hipster nerds and music crazies for two weeks of every year. And a balloon with a 60 t wing span is a hard thing to ask the cops to turn a blind eye to.

Maybe we could have just taken it down to the bridge and flown it at sunset. Freak the bats out a little or left it tethered somewhere along the river bank hovering there for everyone to see.

But that's the thing about a life-size replica of a drone: I don't think anyone would find it ironic or subversive or even a little bit funny. Balloon or not I am pretty sure that people would hate it, instantly, and be unnerved by it in a very primal way.

I live in San Francisco's Mission District which takes re-appropriation and sarcasm as a matter of pride but if I were to anchor this in my back yard or from the top of Dolores Park I expect that I would pilloried publicly, dragged in to court for creating a public nuisance and be the root cause of a lot of people buying crossbows, or pellet guns, with which to shoot the thing down.

At this point we are so over-saturated by images and stories of drones that our lizard-brains take over. Images are defensible. The physical reality of a drone though – its presence and scale – is not.

Aside from the very real military function of a drone I don't actually think that it's drones per se that we find problematic.

Drones are simply the current best shorthand, a manifestation, to talk about a condition of contemporary society that everyone is increasingly becoming hyper-aware of.

An awareness not only that all our actions are being monitored silently (typically in an otherwise benign fashion by way of the digital trails we leave) or not (in the case of systems like CCTV installations) but that they have become the triggers to actions for which there is no warning.

Imagine your credit card's fraud detection system gone berserk. And then imagine that process, to borrow an especially loathesome expression, "weaponized".

I have a layman's understanding of the military so what I am about to say is a bit of reading of tea leaves but it is interesting to consider that the currently strategy of the US military is entirely based around its ability to see at a distance, and out of reach.

The drones we've been told about fly higher than commercial airliners long past an altitude where you can see cars on the road. We only ever see grainy down-sampled video feeds from these devices but the robot eyes of a military camera, we're told, operate in a world of infinite Anselm Adams -esque precision and depth of field.

The natural extension of that strategy is, apparently, to simply place these cameras higher and higher in the sky where their tactical advantage is not simply that they can see further than anyone else's cameras but that they are physically beyond the reach of anyone else's ability to shoot them down.

The military recently shelved plans to deploy blimps designed to hover up around the stratosphere but presumably that's because the operational details haven't been worked out and not because it's a crazy idea. It's no crazier than drones were when everyone looked at them sideways in 2002. It's not a crazy idea because the air force has had an unmanned space ship in actual outer space flying around the planet doing who knows what, for three months longer than it's initial six month flight schedule.

I mention all this because after World War 2 and especially during the 60s and 70s geographers and cartographers were afforded access to a level of remote-sensing and precision mapping that no one had never seen before.

This was, understandably enough, an exciting time. If you'd spent your whole career beholden to the tools and techniques of the last two thousand years and were suddenly given the god's eye view of a satellite you'd be hard pressed not to imagine the how it would change things.

But it also fostered a very particular world view, born as much out of the frustrations of the past as the potential of the new future-present: The idea that maps could finally capture a faithful reproduction of the natural world.

That there is a single reducable and objective truth which can not only be measured and recorded but that punches through and enfolds the boundaries of time and history as well.

This gave rise to a counter movement of voices generally lumped together under the umbrella of "human geographers".

We don't have time to get in to the subtleties of their intellectual argument but the short version is something along the lines of: "That's insane. And not only is it insane, it is fundamentally dangerous."

The human geographers have gone to great, if sometimes pedantic, lengths not simply to assert but to demonstrate that all maps are a series of choices and, by those choices, are a form of control.

This has been valuable and important work because it ultimately questions the idea of the ubiquitous all-seeing data eye. The idea that we can dip in to the slipstream of pure information and ... what? I'm not sure what. I've never heard a really compelling argument for drinking from what we now call the "firehose" that isn't at its core a thinly veiled god fantasy.

In some respects human geography is an intellectual discourse that isn't well-equipped for something like the Internet or the availability and reach of networked screens.

Occasionally the arguments that the human geographers have made verge on the absurb and conveniently ignore the fact that sometimes maps are simply a series of choice dictated by the realities of a finite pixel space. Or that maps are living creatures now, fattened up like a goose with new data and reborn inside a kind of Cylon resurrection ship for geography, usually just called "Google".

But maps are no different than any other firehose. The siren song of all possible voices, or places, is that of all possible choices and as a device for contextualization it's basically useless.

Maps and data visualization are pretty tightly coupled in people's minds these days and I actually think that we'll see the equivalent of the human geographers, but for data viz, in the years to come.

The biggest challenge that data visualization faces as a medium is that people have begun confusing it with actual truth or facts, rather than as an abstraction.

Humans have never not relied on abstraction as a means of survival. Words themselves are abstractions and they are one way that we don't get lost in the weeds. We celebrate the effort of abstraction.

Transposing the intellectual rigour and precision required to, say, model weather patterns on to everyday conversation is like holding yourself hostage to all of space and time.

China Meiville's book "Embassytown" does a better job of discussing this idea so I'd encourage you to read it if you haven't already.

But right now that sometimes feels like what is happening: The recorded output and eventual input of our lives is outpacing our ability to abstract it.

A former colleague of mine showed us her wedding photos over lunch one day. They were, as you might expect, only really interesting to her. She made a comment that stuck with me, though. She said:

"It's crazy. In every single picture I took every person is looking at a different camera!"

Which is not quite the same kind of "bad-crazy" hyper-awareness I talked about at the beginning but it does represent a particular flavour of that same hyper-awareness, where everything is watching itself with not enough time to make determine motive or meaning, that we're all living through right now.

I'm going to close by saying I don't think this is a dire situation. I expect we will adapt. Nor do I think it's a tipping point in to some magic pony world where we bond with our robot overlords and acheive the perfect zen of a rock garden. But it is, as James pointed out when he first started writing about the "New Aesthetic" something... new.

Instead I'm going to finish off by asking a deliberately rhetorical and wooly question. Mostly wooly because on the face of it the question itself doesn't make any sense.

The question is: Have optics rendered pixels obselete? I ask the question in part because I have a theory that media are elevated to the status of captial-A art when they are no longer commercially viable. The history of print-making is a good example of this.

Whenever the military releases satellite or drone imagery for public consumption it is always down-sampled. Pixelated. It's important to consider that down-sampling because that's the world we – those of us without security clearance and left to purchase consumer grade tools – are always going to live in a slightly blurry version of the future.

Do we then need to learn to read those grainy images the way we do paintings and is that part of the reasons we're all so obsessed with pixelating everything these days?

Or is it just a way to make the world defensible again?

Thank you.

And then we took drone

swimming. Literally, not like in this photo. But in a pool. No, really.