still life with emotional contagion

I had the privilege of being asked to speak at dConstruct, this year. Many thanks to Jeremy and all the organizers for the invitation. This is what I said keeping in mind that what you read here is never entirely what I said at the time and often what I meant to say or should have said. If you want to hear exactly what I said there's a handy audio recording of the talk (along with recordings of everyone else's talks too). There's also a really nice episode of the BBC's Click radio program on the subject of and interviewing some of the people who spoke this year.

...

Maybe I am just a bad person but I think if you asked people what it means to live with the Network

in 2014 the answer is something approaching dread and resignation. If we have made the Network like oxygen then it's hard not to consider the air around us to have been made somehow suspect if not outright hostile. To wonder whether the Network itself has not been a kind of bait-and-switch.

So, that's a question I want to poke at today. I want to try and understand whether this feeling is justified or whether it is part of an attempt to shape a larger narrative in the service of someone else's motive.

A couple years ago Anil Dash wrote an essay titled The Web We Lost

and later revisited it as a talk titled How We Lost the Web

. In both he offers a pretty damning critique of people building and working on the web, and in particular a self-identified open web

, in the late nineties and early aughts. He points out that people behaved in such a way that when asked to choose between themselves and Mark Zuckerberg everyone else chose the latter. It is a good and necessary piece of introspection but when Anil talks about a web that was lost I can't help but wondering: Did we really?

I am going to start with three short stories that may seem like non-sequiturs at first but hold on to them throughout the rest of the talk because they are all variations on the same set of questions and concerns.

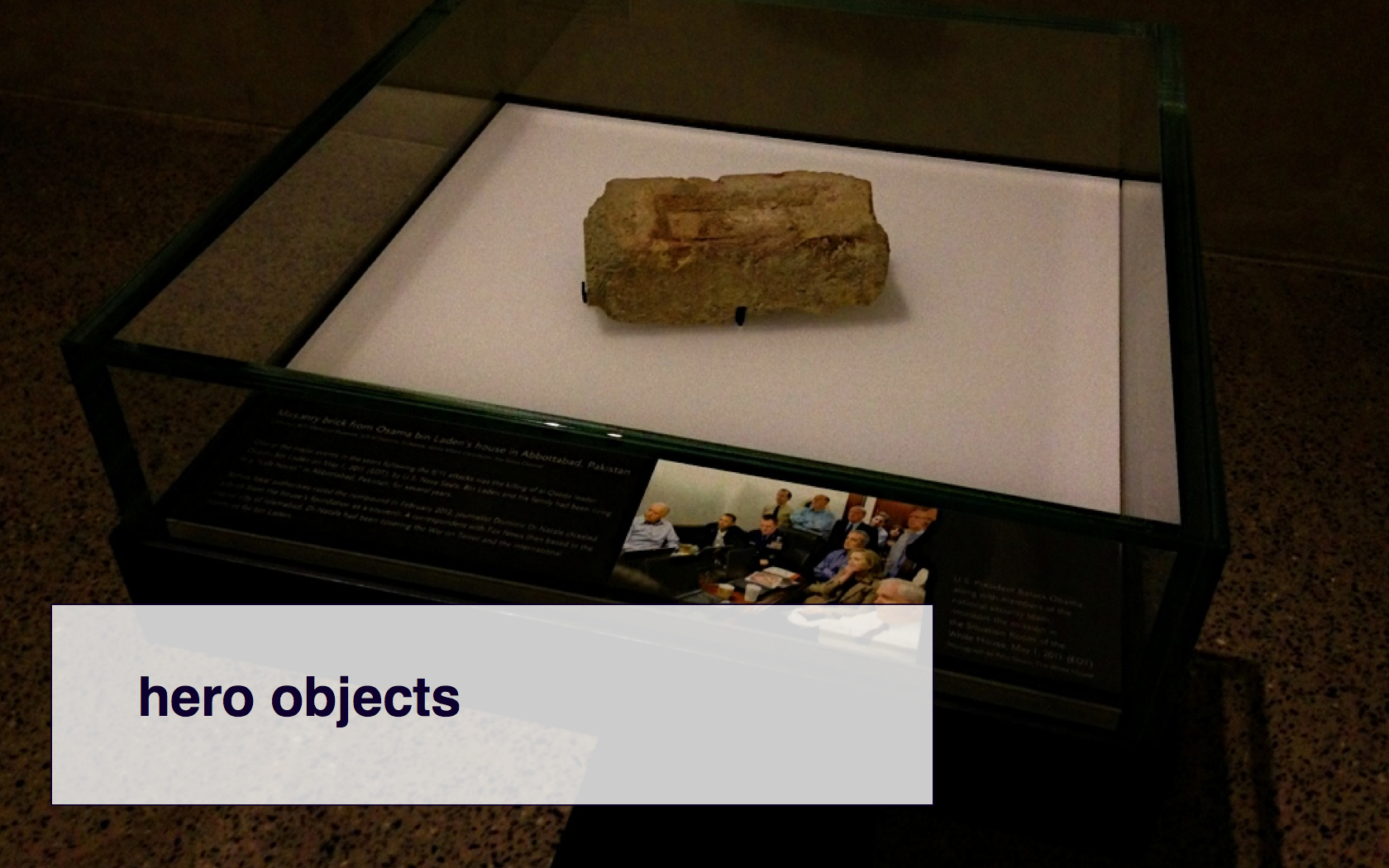

This is a brick. It's not just any brick, though. It's a brick that is on display in the basement of the South Tower of the 9/11 Memorial, formerly the World Trade Center, in New York City.

It's a brick from Osama bin Laden's compound in Abbottabad Pakistan, where he was killed by American special forces in 2011. If you look closely you can see that the display case also has a photo – yes, that photo – of the US President and some of his advisors and cabinet members anxiously watching a live video of the event from the situation room in Washington DC.

I am still at a loss for words to describe this image except to stay that it seems like the most potent example of a hero object

– a proxy device for a larger history and set of shared cues and signals – that I've seen in recent memory. Not the brick itself but the decision to place – or contextualize

as we like to say in the museum business – the brick in this space feels like the encapsulation of every single what-the-fuck moment that has occurred in the last 13 years. From the realization that the planes hitting the World Trade Center were doing so deliberately, to the realization that America was about to devote all its energy and turn all its attention to the question of revenge, to the realization that those orange jumpsuits are now being used as a semiotic media device to... well, it hasn't stopped yet.

But maybe you had to be there to feel this way. In fifty years that brick may not hold any more charge to an eight-year old of the future than a sixteenth-century waterwheel does to an eight-year old today. I honesty don't know what an eight-year old, past or present, is supposed to take away from that brick except maybe a lesson in the construction of triumphal narrative book-ending and possibly schadenfreude.

We could spend all day talking about the 9/11 Memorial and its multiple personalities as a museum, as a mausoleum (literally), as a borderline atrocity exhibition sculpture park and as a genuinely important catalog, or registry, of the principals who intersected with the event: The individuals trapped in the towers, the first responders; the workers involved in the cleanup; the families. Or we could focus on the relationship between abstraction and historical detail – by no means unique to the 9/11 Memorial – and the question of how to convey the meaning and impact of an historical event, over time.

It's a complicated space. Above all it is a luxury – perhaps an indulgence – that New York City and the United States has allowed itself but more than anything I left thinking: Would that every tragedy be afforded the same degree of remembering.

A couple of years ago while attending a conference in the Netherlands I heard the following story. I heard the story more than once but since then I have not been able to confirm the facts or the institution in question so you should take what I say with a commensurate grain of salt.

The story goes that as a consequence of the 30% across-the-board funding cuts to cultural heritage organizations, from the European Union, that one institution had been forced to de-accession something on the order of 30, 000 objects. To make matters worse the institution was not only forced to de-accession the objects but, presumably because of staffing and resource issues, were not in a position to find anyone to acquire the objects in kind. So they binned them. They literally tossed 30, 000 objects that had previously been deemed important enough to keep in a museum or archive in to the garbage.

What strikes me about this story is less the decision, unfortunate as it is, to discard all those objects but rather the opportunity not seen or acted upon: Why not offer the public the chance to safe guard those objects until such a time the museum might be able to reclaim its custodial duties. Which may be never but it's the sort of thing that could be accomplished with little more than a spreadsheet listing the accession number of the object in question and contact information for the person who has taken that object in to their care.

Remember: All the objects are already set to go to landfill so any attempt at preservation is forward motion. Even if 5% of the participants were to drop off the face of the planet and another 5% were to destroy their objects that still means you've managed to save 27, 000 objects. Not to mention fostering a sense of ownership and participation in the act of preserving cultural heritage.

Update: According to Marrije Schaake it turns out the institution in question was able to save all those works in the end.

It's worth considering that archivists – as a professional class – have only ever known – in an historical time-scale – war and looting and pillaging and general strife. Which means they have done a more than pretty good job of it when seen in that light. Despite occasional losses or lapses of professional or ethical judgement along the way they have kept most of the things safe under some pretty dire circumstances.

So it's not hard to imagine that they – and again I'm speaking of the entire professional class in the abstract – might express some doubts about the long-term viability of something most of us can't even conceptualize: electricity. And given their experience they would be forgiven for holding that opinion. That is something to think about whenever we talk about digital preservation.

Okay, now I am going to commit the cardinal sin of technology-related conference talks so I am going to try to both do it in spades and make it fun.

I am going to quote William Gibson. Not only am I going to quote William Gibson I am going to quote the single most quoted passage he has written. The passage that has been quoted so many time that, like the city of Florence which has been photographed so many times, it no longer exists.

Then, I am going to quote William Gibson, again.

You are under no obligation but since Jeremy is recording the audio of this talk for posterity I'd like to invite to read along with me, at the top of your lungs.

I know, right?

No, really...

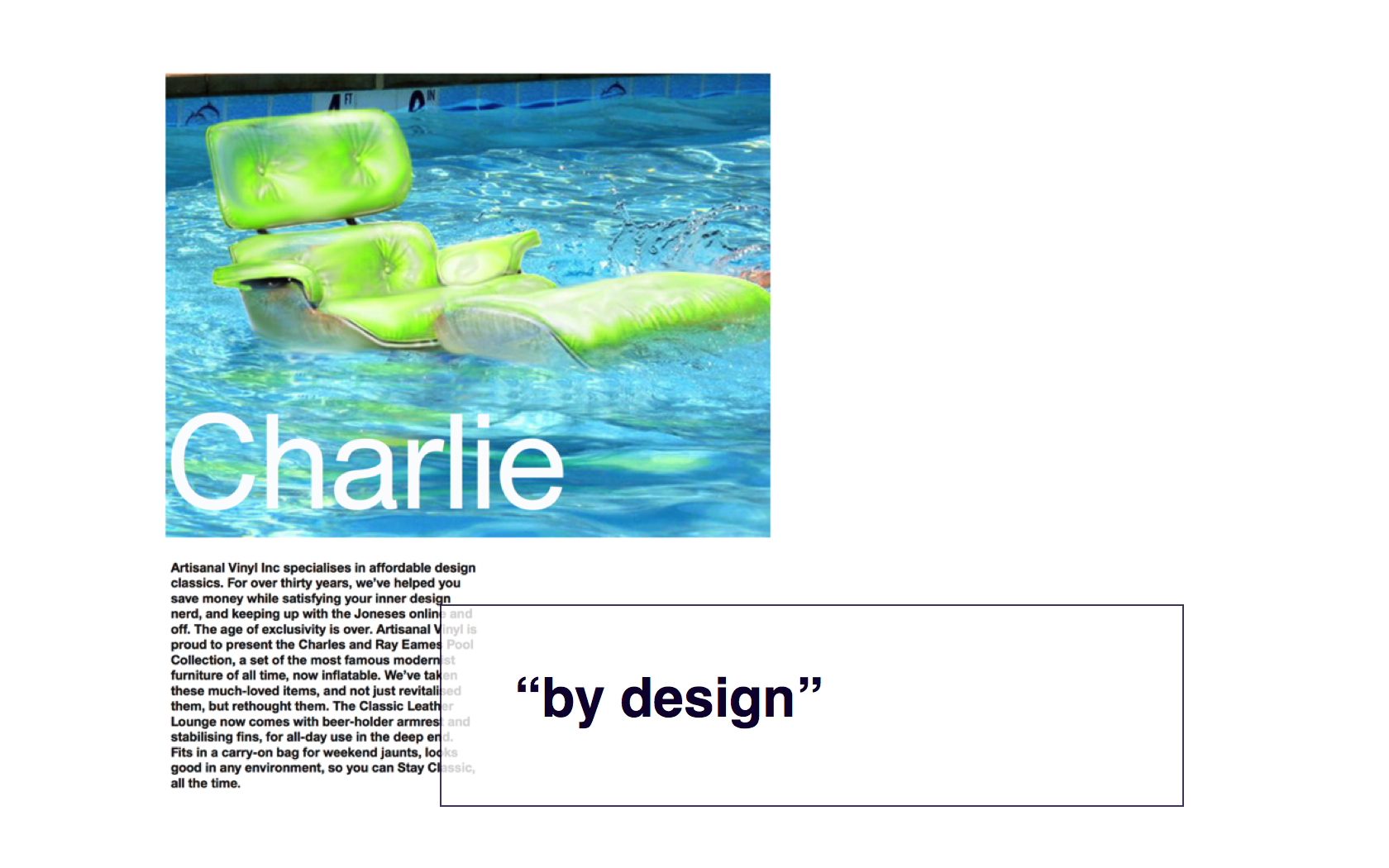

What interests me about those two quotes is that they are essentially saying the same thing, but you rarely see them paired together. These two passages seem to me to be two sides of the same coin separated by a vantage point that is usually measured in economic means. They are interesting to me as someone who works in a design museum because the pairing of those two ideas nicely sums up one of the characteristics, or even dilemmas, most design museums have had building their collections.

That is: We have a fondness for and a bad habit of focusing on, sometimes exclusively, a kind of shiny and glossy future that has arrived only for the few who can afford those concept pieces and limited edition runs which are themselves often little more than proxy objects that trade an association with and access to high-end manufacturing technologies for merit and value.

They are, no doubt, beautiful objects but the rationale for collecting them tends to fall apart when measured against the question of function in service of an audience.

It is my position that a design museum should be spending a lot more time collecting and studying those objects that you might associate with the second quote: Those objects where the street

cobbles together to create a solution out of necessity and ingenuity absent the ability to simply burn the problem away with money.

In the Cooper Hewitt's defense we try to do some of this with Cynthia Smith's Design for the Other 90% series which is pretty much what it says on the tin. We should all of in the Business

do more of it, though.

What both of the quotes share is the awareness of opportunity and an intention to exploit it.

In economics opportunities are sometimes called efficiencies

which, as I'll try to demonstrate, has always struck me as a bit of a misnomer. Sometimes they are referred to as production functions

which might only have a charm if you're a computer programmer or a math nerd. I prefer the more colourful but no more benign seeing in to the future

.

They all speak of opportunity as the ability to influence circumstances a direction of one's choosing. It says nothing of a guaranteed outcome. Nor does it suggest that opportunity is or need be universally visible. As often as not opportunity is only seen as opportunity in so far as it can remain a closely guarded secret deployed opposite someone else's ignorance.

High-speed trading remains the poster child for this phenomena precisely because the worst part of all the havoc that the practice has wrought on the financial markets is that, until we legislate otherwise, the traders involved haven't actually done anything wrong. They are simply those people who took the time to carefully read the mechanics, literally, of how high-speed trading works and saw an advantage – an opportunity – inherent in the system that no one else had noticed and then proceeded to exploit it.

And opportunity may not be seen even when it is hiding in plain sight. I often cite OpenStreetMap (OSM) as an example of this because it feels like an instance of pure crystalized opportunity that still remains too abstract for people to wrap their heads around it.

OSM is in many ways the realization of a particularly wooly-eyed happy-happy dream a lot of people had of the Network and the web, in particular:

- It is built bottom-up by a community of passionate users

- It is a source of high-quality, and constantly improving, free and open data

- It comes with a large suite of open source tools for doing stuff with all that data, that is increasingly find new uses in entirely other projects

- It has a convenient sticking-it-to-the-Man back-story (sorry Ordinance Survey)

- It's just sitting there, patiently waiting to be used when you're ready

And finally, they're maps – those singular tokens representing an expression of history and control that used to be firmly in the hands of a small and not always well-intentioned elite. OSM provides all the raw material to challenge that system.

OSM still has a steep learning curve but you might think that given everything I've just described a lot more people than have would have seized on the opportunities that being able to create, to dictate, their own maps would afford. It just hasn't happened yet because, and there is no subtext or judgement in what I'm about to say, it's still a shape foreign to most eyes.

On the other hand some people get paid to sit around all day doing nothing but look for opportunities and avenues to exploit them in pretty much anything they can get their hands on. It's not just the intelligence services of the world but they enjoy that privilege on a scale no one else does. In turn, we bestow on them the fruits of our own imaginations in the ways we consider how they might seize on the opporunity, independent the reality, such a privilege presents them.

Have a think about that the next time you read an article about the documents leaked by Edward Snowden and any other still-unnamed whistle blowers.

The other professional class who enjoy this status are the so-called cool-hunters

whose job is to look for patterns in the mist. To frame those patterns as understanding and by extension opportunity and ultimately influence.

I once had a painting studio, back in the days before the Internet, which shared a balcony with a guy whose job was to read stacks of magazines about politics and policy journals and synthesize all that information in to reports. I have no idea what happened to those reports but he would sit on the balcony all day, exercising the influence of his opinion, from a comfy chair which made it seem like a pretty good job.

It's important to remember that many of the earliest descriptions and articulations of weblogging, by people who had a vested interest in the story they were telling, are almost exactly like the job I've just described only distributed and hyper-specialized and without the bottleneck of someone else's financial burden or approval to publish.

And let’s be honest: That is something which has worked out pretty well, to varying degrees, for most of the people in this room or who would like to be in this room. The many different shades of weblogs, which really just means the web, quickly became vehicles with which to use personal brand as a kind of non-state actor for influence.

Seen in the cold harsh reality of something like this photo, though, it is easy to understand that what we have dubbed clickbait

as the ultimate commodification and realization, possibly even democratization, of cool-hunting.

This is where it starts to get murky. It gets murky because I could be wrong about this and even if I am right there is not necessarily the convenient satisfaction of a conspiracy at play. What I am trying to describe may just be a confluence of opportunities.

But there is definitely something in the air in the way people talk about what success looks like and how its measured and how it compares to other successes; things are measured in “kill time” with the assumption that there is only one chance to exact influence.

If the shelf-life of a success is measured in its fall-off rate for orchestrated clicks

or views or the rate at which an action yields more followers

then there is only the next thing. There is only now or, rather, even if there is a past there is no time valued enough to consider it.

The question I’ve been asking myself is whether by our focus if not our action we start to warp the underlining architecture – the conceptual architecture as much or more than the technical one – of the Network. Specifically those properties of the Network that made us fall in love with in the first place.

I can't decide if its a question of transience being normalized or permanence being denormalized but when the measure and mechanics of success dictate that we return to a model that we tried before and no one particularly liked – namely television – I can't help but wonder what we're doing. And why.

We are living through a rhetoric of ephemerality that seems to have two principal characteristics:

The first is that I think it benefits – in the otherwise benign and opportunistic manner that we grant private enterprise – a particular business model so there is cause from some quarters to champion it. If nothing else operating a broadcast pipe that does not have to concern itself with the messy issues of access and retrieval makes running a business that much easier. This is the phenomenom I sometimes describe as engineering decisions being passed off as philosophy

.

The second is that I think it is understood though perhaps not articulated as a coping mechanism. In a world where we are told that the intelligence services are tapping the physical cables that make up the Network and that they really do want to write down everything you do in your permanent record or that, as has happened in Australia, all of that information may and probably will be used against you in a court of law it's tempting to imagine that there is such a thing as ephemerality.

Which is problematic because it replaces what is fundamentally a social question – one of means (how data is collected) and admissibility (whether information collected in a manner contrary to the social norm is acceptable) – with a technical solution that from a practical-like-how-does-it-work perspective is fantasy.

Why is this important? One articulation of why can be found in Anab Jain's Valley of the Meatpuppets in which she writes:

Go now, and read the entire thing. I'll wait...

Or put another way: Recall has always been a power dynamic.

You see this throughout history: In the right to assembly; In the question of access to basic literacy; The entire notion of a public library; The restrictions around intellectual property; Paywalls and the rights to broadcast or re-broadcast. Whether it's been through malice or negligence or simple circumstance the ability to not only see in to the future but see in to the past has not been an opportunity open to all.

More recently work around memory reconsolidation

which, through the use of protein inhibitors, has allowed researchers to seemingly erase individual memories in lab rats. This is all work that's being done to help remediate conditions like PTSD and other traumas but if it is found to be successful in humans you can be sure that it will become political.

This is what makes the Network and the web in particular so important:

The web gave us the ability to return to a thing outside the shared (or master) narrative at a time of one's own choosing. Of shifting time in the service of one's own interest or in the service of simply coming to an understanding of one's own interests.

It lowered the barrier to speak to the future and to listen to the past. Not because we know why or can quantify its return in advance but because we believe what is most important is simply the ability to do so.

Access and access at the time of your own choosing is a subtle but important distinction and if we are talking about the opportunity of the Network itself, it is this.

Imagine a world in which access to an exchange of culture required we all have to gather around our computers at the same time in order to read Maciej's latest blog post. Some of us can and if you asked I would tell you it sucked.

When television was the only opporunity we had to gather together outside of and to imagine a world larger than our immediate surroundings we managed to craft genuinely meaningful experiences from it. It would be wrong to suggest otherwise but it would equally wrong to ignore how quickly we opted for the alternative modes – opportunities – that the web provided.

I think that should tell us something and that it is perhaps a quality of the Network being overlooked and perhaps being lost entirely as we devote more and more time and infrastructure in an effort to going viral.

Because we are not all, or will not always be, the kinds of people seeking an audience of many. What the web made possible – at a scale never seen before – was the ability for a individual to discover their so-called community of five

. In time. It was the ability for one person to project their voice and for it to echo out across the Network long enough for someone else to find it. It gave us the ability to warm up to an idea, to return to it.

That access to recall is what makes the Network special to me. That is the opporunity which has been granted to us which we would be wrong to confuse with success or even discoverability. We all suffer from degrees of not-in-my-lifetime-itis but that is a kind of deviant behaviour we have already perfected so maybe we should not apply its metrics to the Network, for everyone's benefit.

As has been mentioned I work at a museum. As part of the museum's re-opening in December we are building, from scratch, a custom NFC-enabled stylus which we will give to every vistor upon entry. The stylus (or pen) will allow you to manipulate objects on interactive tables as well as to sketch and design your own creations. That is, literally, what the pointy end of the stylus is for.

The other end is used to touch an object label and record the ID of the object associated with it. That's it. Objects are stored on the pen as you wander around the museum and are then transferred back to the museum during or at the end of your visit and are available for retrieval via a unique shortcode assigned to every visit.

If you buy a ticket online and we know who you are then all the items you've collected or created should already be accessible via your museum account waiting for you by the time you get home or even by the time you get your phone out on the way to the subway. (If you don't already have an account then the visit is considered anonymous

and that's just fine, too.)

The use of the pen to collect objects has a couple of objectives:

- To simply do what people have always wanted to be able to in museums and been forced to accomplish themselves: To remember what you saw during your visit. People take pictures of wall labels, I think, not because they really want to but because there is no other mechanism for recall.

- To get out of the way; to be intensely quiet and polite. The pen will likely enjoy a certain amount of time in the spotlight but my hope is that it will be successful enough that, when that attention fades, it might simply be taken for granted. To be a necessary technology in the service of memory, that dissolves in to normalcy, rather than being something you need to pay attention to or have an

experience

with. - To give people the confidence to believe that they don't necessarily need to do anything with the things they collect in the moment. To have the confidence to believe that we will keep the things they collect during their visit safe for a time when they will once again be relevant to them. For a person to see the history of one visit in association with all their other visits.

The pen itself is a fairly sophisticated piece of technology because it turns out that taking the conceptually simple act of bookmarking

objects in real-life and making it simple in hardware and software is still actually hard. We are not doing this simply for the sake of the challenge but because it provides a way for the museum itself to live with the Network. In these ways we are trying to assert patience. We are, after all, a museum and our only purpose is to play the long game.

I totally didn't say that last paragraph on stage. I should have, though. Instead I talked a little bit about oh yeah, that which is a photo-sharing website which lets you upload a photo and then doesn't let you see it for a year. I talked about it as an experiment in a kind of enforced patience with the Network. I also talked about it an exercise in trying to build a tool that could operate without the adult supervision of my time or money (or much of it, anyway) such that it not be subject to the anxieties of being immediately successful. This, it seems to me, is the work ahead of us. It is not about oh yeah, that or any particular class of applications but about understanding why we are doing this at all and building things to those ends.

If you haven't read Thomas Piketty's Capital in the 21st Century I would recommend you do. One of the things that makes the book so powerful is that Piketty has been able to shape an argument through the rigorous use of historical data across a number of countries. The data is incomplete in historical terms: The data for the UK is only available from about the 1840s onwards, for the US data becomes available in the 1920s and so on. The one country where the data is available in a comprehensive manner is France. Because they went to the trouble of collecting it. One of the first acts of the state following the French Revolution was to perform an audit of and to continue collecting reliable estimations of wealth and property.

It is that diligence in record-keeping which made it possible for Piketty to illustrate his point in fact rather than intuition. On the web we have been given a similar opportunity to project our stories outwards in the future; to demonstrate a richer past to the present that will follow this one. It is unlikely that it will or even should yield the same fact-based analysis as Piketty's book. That is not the point. The point is that if we subscribe to a point world view that values a multiplicity of stories and understands that history is nuanced across experience and which recognizes that the ability to look backwards as much as forwards is where opportunity lies then we would do well to remember that many of those aspirations are afforded by the Network and in particular the web.

Those qualities are not inherent in the Network no more than access to opportunity guarantees success. They require care and consideration and if it seems like the Network has turned a bit poison we might do well to recognize that maybe we have also been negligent in our expectations, both of the Network and of ourselves.

Damn... you can almost see me exploding in to a TED-sized supernova of emotive jazz-hands at this point. As above, I did not in fact say this while on stage. I tried to say something like it, though, because I think it's true.

One refrain I hear a lot these days is that it's all gotten too hard

. That the effort required to create something on the Network and effort to ensure its longevity has morphed in to something far beyonds the means of the individual. I am always struck by these comments not because I think we ought to be leveraging-the-fuck out of the latest, greatest advances in application framework or hosting solutions but for the simple reason that:

We managed to build a lot of cool shit on the back of 56Kb modems. We built a lot of cool shit – including entire communities – on top of a technical infrastructure that is a pale shadow of what we have available to us today. We know how to do this.

It is important to remember that the strength of the web is in its simplicity but in that simplicity – a Network of patient documents – is the opportunity far fewer of us enjoyed before it existed. The opportunity to project one's voice and to posit an argument which might have even a little more weight, or permanance, in the universe than shouting in the wind which is all most people have ever enjoyed. The opportunity to be part of an historical dialog because having an opinion is not de-facto over-sharing

.

It is important to remember that the Network has given us the opportunity of a different measure of success.

About a month after dConstruct I did another talk, as part of Eyebeam's LittleNets exhibition, titled this is my brick / there are many like it but this one is mine. The two talks can be taken separately but at the same time they part of the same larger conversation.

This blog post is full of links.

#dconstruct