We Were Otaku Before It Was Cool

I gave the opening keynote at the Access conference, in Montreal, last week. I stayed for the rest of the conference and had a lovely time, seeing some old friends and meeting new ones. Props to Ed and Amy for doing an amazing job organizing the whole thing, and for sweating the details like wrangling a 29-dozen bagel run for people on Sunday morning.

If you look carefully at this talk (by which I mean: past the Roombas) I think it's interesting the places where it starts to overlap with the talk about motive during the New Aesthetic panel earlier this month. That wasn't a thing I spent any time dwelling on. It's just a thing. This is what I said:

A couple of quick historical notes before we get started:

First, this is apparently what the Unitarians, one of whom was my great-grandmother, were up to in 1891. Second, in 2012 you can no longer find corn doilies

or at least not easily.

The community craft site Etsy does not list any such items (which is kind of shocking when you consider all the other things they sell) and, when asked, Google helpfully suggests that you may have more luck searching for corn dollies.

Hello!

It is my pleasure and my privilege to be here today and to be given the opportunity to do the opening keynote. It is especially nice for me to be back in Montreal because, although I've been away now for almost eight years first in San Francisco and now New York, this is still home.

Montreal is, as the expression goes in French chez moi

.

This is a photo of one of my favourite pieces of local graffiti, taken in 2003. There's a condo now in the place of that parking lot which means in theory the painting is still there waiting to be discovered, to be restored even, by some possible Future Us.

I was chatting with a friend the other day and he asked me what the thesis of this talk was. On some levels I don't have one. On some levels it may be too soon for thesis statements. What I want to do here, instead, is work through a series of ideas that argue in a general direction. I want argue that something is happening.

Something that, to a greater or lesser degree, we may not need to address today or even tomorrow. But, in the way the day-after-tomorrow always gets here sooner than expected, we should probably start thinking about today.

I am here for the entire conference so to the extent that you agree or disagree with me – and especially if you disagree – please come find me for a chat.

Otaku.

I learned about the idea of otaku in the first (or second) issue of Wired magazine, in that near-distant past when we still found out about the rest of the world from little packages of media defined by regular intervals of space and time.

The term is Japanese and refers to those subcultures that obsessively collect things, typically low-brow pop-culture subjects. Despite being considered a pejorative, by some, the term has been all-purposed to denote any kind of serious but still amateur collector.

While I was looking up exact definitions of the term I came across this passage from William Gibson's novel Idoru:

The otaku, the passionate obsessive, the information age's embodiment of the connoisseur, more concerned with the accumulation of data than of objects, seems a natural crossover figure in today's interface of British and Japanese cultures. I see it in the eyes of the Portobello dealers, and in the eyes of the Japanese collectors: a perfectly calm train-spotter frenzy, murderous and sublime. Understanding otaku -hood, I think, is one of the keys to understanding the culture of the web. There is something profoundly post-national about it, extra-geographic. We are all curators, in the post-modern world, whether we want to be or not.

With that in mind I'm going to start this presentation by telling three short stories, one from each of the last three years.

This is a screenshot from Flickr. It's a gallery of, as the name suggests, President Obama fist-bumping people.

Galleries at Flickr were a thing that we introduced in 2009 as a way to encourage the membership to start thinking about how to represent the breadth of not only the sheer number of photos available on the site but also their individual experiences with them.

By the time we launched Galleries there were already five billion photos and somehow people thought we were going through the pile every day curating photos for the "explore" section.

There were only two rules for Galleries: A single gallery could have no more 18 photos and none of them could be photos that you, as the gallery creator, had taken. That was it. The goal was to focus people not on any specific theme or topic but on the act of choosing.

I did a paper about Galleries, in 2010, talking about the larger trend of people not only discovering but starting to flex what I called a curatorial muscle.

I talked about how there was a still nascent but very confusing smushing up of the roles and distinctions happening between traditional critics, experts (or curators) and docents. This felt like a similar blurring that had been going on for a while between art and craft and design.

I came back to this a year later when I was asked to be on a panel about art and cartography. The question of useful versus simply pretty maps is perennial in cartographic circles and it reminded me of the arts versus crafts debate I had grown up with in art school.

I studied painting in the mid-90s at a time when the debate was especially vicious. It was mostly a lot of name calling and questioning of motive between the "fine" artists and the people practicing craft. The designers were mostly relegated to the status that cartographers are afforded today: Everyone knows there is both a skill and an aesthetic to their work but no one is willing to call it captial-A art.

I think part of the reason that the debate was so brutal in the 90s is that we could all feel the ground shifting under us but no one could understand how or why. Fast-forward to today and it's pretty clear what was going on:

The economics around production and distribution that have, until now, buttressed the distinctions between art and craft and design have all but bottomed out today.

We live in a world where design studios are routinely criticized for producing "art" pieces devoid of any functional purpose. Where artists are designing products for luxury brands. Where craftspeople are finding success and audiences on the internet and, in may cases, raking in money hand over fist.

The reason I mentioned this is that we have often used the cost of something as a proxy for its value. Where the cost might be concrete dollars and cents or, especially in the case of cartography, the more abstract cost of time and attention. Why would anyone spend ten years of their life making a thing unless they were serious and earnest in their endeavour?

Which really means why would they forfeit ten years of the chance to do something else, which is itself another way of saying time is money.

The problem, today, isn't so much with that equation but with the counter-equation: That things (or at least maps) can be evaluated by the ease with which they were created.

Not all maps are equal in their craft or their consequence but the technology stack around map-making has moved so far and so fast in the last few years that you can, in fact, make a very good map easily.

As a result one measure of confidence in our ability to judge things has gotten completely messed up and we are still trying to find new bearings.

This is increasingly happening with robotics, too.

This is the shortest of the stories because I am still trying to make sense of the experience I had, earlier this year, sitting in during an informal conversation between a robotics engineer and a group of new media artists and watching them try to figure out where robots are supposed to fit into the cultural spectrum.

Engineers it turns out are the new folk art.

I am telling you all these things because I want to use these stories to set up an idea that, to my surprise, has proven to be a really good way to pick a fight with people in the cultural heritage world.

That the distinction between museums and archives (and by extension libraries) is collapsing in most people's minds. Assuming it ever existed, in the first place.

When I say the distinction I mean both the roles themselves and their relationship to one another. And when I say collapsing I don't mean to imply a catastrophic end of days but rather a kind of simultaneous "passing-through" of any one field through all the others. A smushing together.

Consider Rhizome's ArtBase which calls itself an online archive of digital art. I've lived in Quebec long enough to see my share of province wide power outages so I know that electricity is the weak link in all of this but: To the extent that ArtBase is always on

and searchable it's no longer clear to me whether it's an archive, an index or a showcase.

Or, as we continue to digitize all the things, all of those things. At the same time.

Here's part of the reason why I think this is happening.

This is a photograph of a warehouse equipped with robots from Kiva Systems. Kiva was purchased by Amazon last year. A year or two before that Amazon purchased the online shoe retailer Zappos as much for their expertise in warehousing – in the art of space-fitting a gazillion boxes of shoes – as for their customer base.

These warehousing systems, and the robots that work in them, are amazing pieces of technology. They are terrifying in their own way because by virtue of their robot-ness they allow for an efficiency of storage and retrieval in ways that aren't possible for humans and our puny meat-y limbs.

It is a system that humans, unaided by robots and sensors and algorithms, simply don't understand. I have friends who've visited some of the warehouses and they report that there are lasers on the ceilings whose purpose is simply to direct humans to move items from one shelf to another.

Which seems sort of grim and, well, in-human on the face of it. That is the conventional thinking until you actually buy something from Amazon and have that thing show up the next day.

There are some very real costs associated with this bit of magic that may dictate its longterm viability but, all things being equal, I have never met anyone who wants to go back.

Short of promoting a particular noxious smoke and mirrors around the idea of "artisanal warehousing" this is the future because it makes possible a kind of expectation around access and delivery.

It's access and delivery to things like books and cat litter today but if we can make it work for those sorts of generally trivial things I am pretty sure we're going to start expecting it for the important stuff.

For a while now I've been threatening to do a talk titled: Can we please put the Impressionists in the basement for 100 years. At least.

Needless to say these are also fighting words in some quarters.

The argument isn't so much about whether or not I like the work of the Impressionists or whether or not I dispute their importance. It has nothing to do with the Impressionists, really.

They are just a convenient short-hand for a class of works, or objects, that are taking up space both physically and intellectually. They are by virtue of our inability, or unwillingness, to figure out a more effective means dealing with their inertia – of their storage and retrieval – crowding out the rest of our collections.

Which begs the question of why we're keeping all that other stuff at all. I will come back to that point in a couple minutes.

The mechanics of how you show, of how you demonstrate, the breadth and complexity of a collection is real work. Hard work. All you have to do is look at the Explore pages on Flickr, to see what I mean. And the number of institutions who can afford the sort of investment that Amazon is making in automating its warehouses is probably close to zero.

The next day Mike Kastellec gave a talk about the work they are doing building out the new Hunt Library at the North Carolina State University, including their automated book delivery system (aka the BookBot) so maybe not as close to zero as I thought, which is encouraging.

But if not laser-guided robots, then what? Everyone gushes over those time-lapse photos of a Roomba trying to find its way around a room.

What is the like that

for our collections?

Deep breath.

This is the part where I am probably going to get in trouble, at work, so I will deny ever having said any of this out loud or in public.

Some of you may already know that the Smithsonian recently launched a national re-branding campaign in the US. We're doing a big ad blitz under the motto: Seriously Amazing.

I want to emphasize that I very much chose to work at the Cooper-Hewitt, and by extension the Smithsonian. I believe in the mandate of the institution and that it is publicly funded and that what those things represent are important. In short, I drank the KoolAid.

But I have a couple problems with the rebranding.

First, I'm not really sure how anyone hoping to reach the so-called young people of today can not be even peripherally aware of meme culture and somehow miss the part where they are walking in to a minefield of LOLCAT jokes like this one.

Second, we are bucketing our audience in to kinds of aspirational typecasting usually reserved for buddy movies – things like the "new" and the "hip" and the "mommy blogger" and so on – instead of simply talking about what we collect and why.

Or this. This is a real photo.

We could have run nothing but this photo, never mind the funny-haha text. That's just a piece of ancient internet meme history I added for kicks. If we'd run this, with the Smithsonian logo at the bottom of the photos, on buses and billboards I bet we'd have generated more excitement than anything the current or past ad campaigns have.

And all we'd be doing is showing people what they've trusted us to keep safe.

I'm not sure whether I'm looking at an archive, here, or a museum or a library (albeit one with very feather-y index cards) and honestly I don't care. Because everything about this photo is pure gold.

The Smithsonian has 18, 000 light fixtures. The Cooper-Hewitt alone has 5, 000 buttons and a frightening number of matchsafes. The zoo at the Smithsonian has pandas. Real live ones. We have a lot of dead parrots, apparently. The list goes on. For a while. And people love us for it. People love us for it because by preserving these things we keep open a narrative space in which to consider the meaning of things.

We are the time keepers. We could have simply published posters that said: We were Otaku before it was cool.

This is not one of ours. It's a photo of an installation piece shown last year in Amsterdam. It's meant to be all the photos uploaded to Flickr in a single day. It's meant to convey the breadth of stories and motive of use behind all the tiny glimpses of life we capture in photographs.

This is my friend James Bridle visiting the exhibition. That's James being happy. I've never seen the installation in real life but every time I see this photo it makes me happy too.

This was James Bridle's reaction, about 5 minutes later when he discovered that there were actually hollow forms over which the photos had been placed.

James eventually wrote the curator of the piece who wrote back saying:

In the installation I'm trying to give a representation of the amount that is uploaded every day on Flickr. On October 6th I downloaded for 24 hours the images tagged as 'IMG' and in weight higher than 900K. This resulted in 950.000 downloaded images. I wanted to show the photographs as a sea of images, therefore I had to create the 'hollow mountains' in the installation. But the volume represents these 950.000 images. I'm sorry if I have disappointed you with this, but hope this mail will clear things up a little bit.

Really.

This is a patch that the Government Digital Services team, in London, made for themselves to celebrate the successful launch of the new gov.uk site the other day. It's a remarkable piece of work, both in its ambition and its execution.

What I especially love are those three words at the bottom: Trust. Users. Delivery.

I know some of the people on the design end of GDS and one of them, I forget who, used a lovely expression to describe their work. They said: There is no design, there is only reckoning.

I tell these two stories because I want to emphasize something: That we are afforded the luxury of taking care of this stuff but we betray people's trust at a very real cost.

This is another photo from a member of the GDS team, taken as they began work on the redesign. That, right there, is your buddy movie. This sort of thing gives me hope.

We are held to a higher standard and a different social contract than we make with the mundane realities of survival that fill our lives. I believe that comes the responsibility not only to have confidence of our collections but the trust that people will figure it out. Just maybe not on our terms.

Speaking of which, did I mention that the museum I work at is closed until 2014? That puts us in a awkward position when talking about some of these things but at the same time forces us to really think about how people access and interact with our collections.

My job is to help figure out what it means to make the museum native to the internet and then to actually build it.

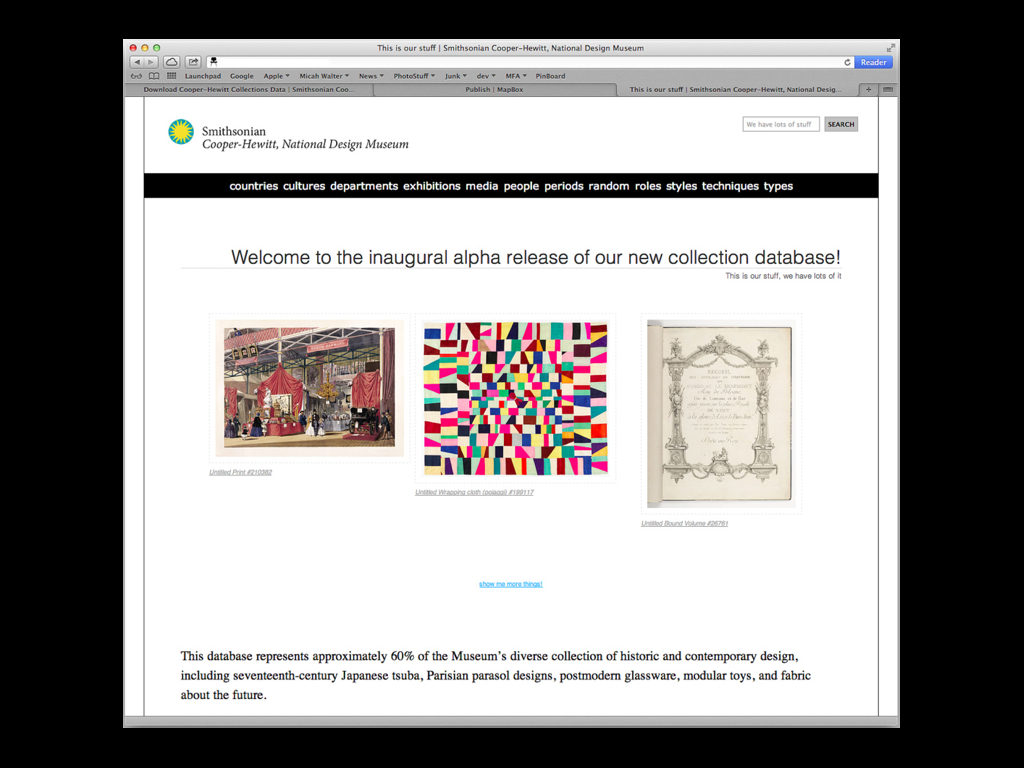

We've just released a public alpha of our new collections system. We have replaced the traditional eMuseum system, used by so many museums, with custom software and we are building interfaces and indexes to tailored to our needs and not the abstract pony-soup of so many packaged solutions.

We are trying to generate concordances between the people, and eventually the objects, that we know about and the people that other museums like MoMA or the V&A know about. We are actively figuring out what it means to hold hands with Wikipedia. We are thinking about pointers, about things that the rest of the Internet can use as stable fenceposts and reliable markers.

This is just the alpha. There’s a lot of work left to do.

The larger existential questions I've been discussing are not the ones we are asking the people interested in our collection to spend their days and nights thinking about but they are the things that I am considering as we move forward.

They are a kind of soundtrack music to the day-to-day effort of building a catalog that serves both scholars and casual visitors, equally. Looking forward we are trying to imagine what it means for the network itself to access our collection. We are trying to create a tool that does not presume, or dictate, a uniformity of motive.

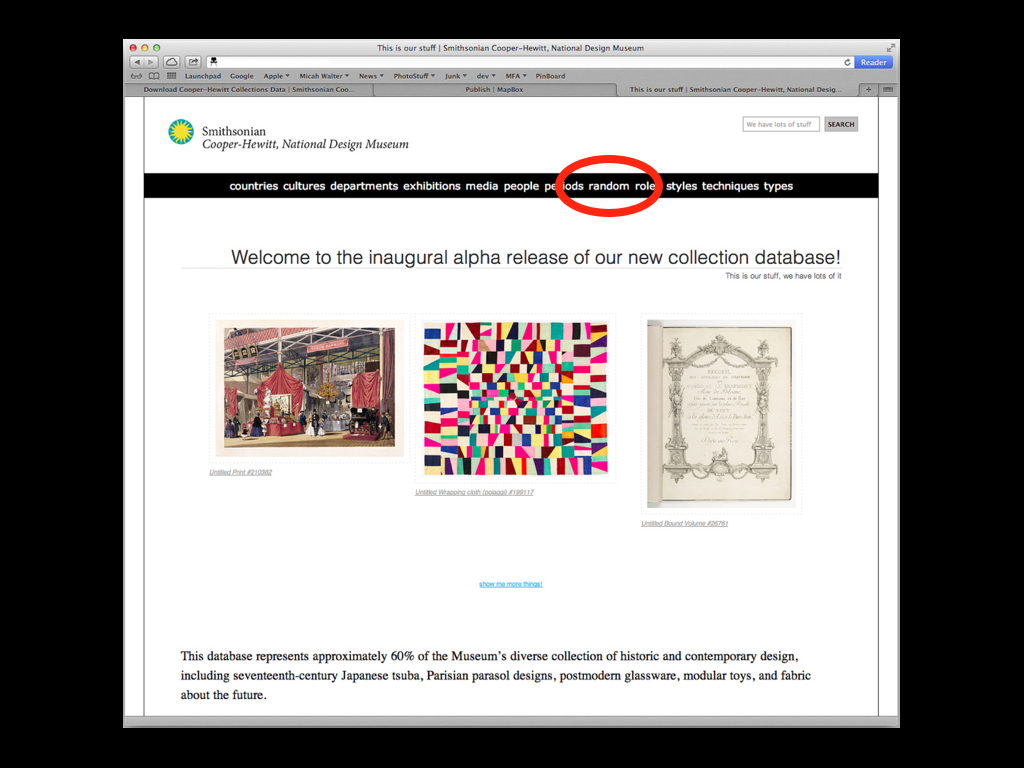

Aside from all the stuff like persistent and stable identifiers and making almost everything a first-class resource on the web – of imaging every facet of our collection as URLs – one of the simpler things we've done is to add a random button.

To make explicit a kind of literal random access memory to our collection.

The random button is scoped only those objects with one or more photos. That's really important for us and for any institution that hasn't finished digitizing their collection.

Most of our collection is still nothing more than tombstone data often with incomplete descriptive data. That's fine. That's our history and we've proven that we can get things done despite those shortcomings but we live and breathe this stuff in a way that most people don't. It's unfair to demand that people suffer those details as a precondition to using our collection.

It turns out, we have a lot of weird stuff. My colleague Micah Walter has started a Pinterest board titled Random Button full of all the wonderful stuff he's found poking around our site.

We are, all of us, burdened by stories of success and growth that resemble the curve of a hockey stick. We should all aspire to that but it is important to remember that it doesn't always happen that way and that patience (and by extension confidence) in an endeavour is as important as making a splashy debut.

Sometimes it takes people a while to see or realize the consequence of an opportunity, for the simple reason that we all lead busy lives. We need to not simply provide access and delivery but to ensure that we do it in a way that lends itself to people adapting it to their individual lives. There are many ways. A random button is just one.

Again: There is no design, only reckoning.

Because this is what 2012 looks like for museums.

It is most definitely not about Twitter but about the fact that some random person out there on the Internet is building a record of understanding about Roombas that may well rival anything we will ever do ourselves.

Beyond that, we are being forced to accept the fact that our collections are becoming alive. Or at least they are assuming the plausible illusion of being alive.

We are having to deal with the fact that someone else might be breathing life in to our collections for us or, frankly, despite us. We are having to deal with the fact that it might not even be a person doing it.

I mentioned we are rethinking the collection in terms of URLs.

This is one of the things that it makes possible. We're not doing anything yet with these photos of Roombas on Flickr, (machine) tagged with the object ID for the Roomba in our collection, but we'd like to.

As an organization we encourage visitors to take photos of our stuff. By making the the individual items in our collections first class objects on the network we give people a way to address them. We give them a way in the words of my colleague Seb Chan to connect theirs to ours

. And vice versa.

And in the way that only Australians seem to get away with saying things like that...

The Cooper-Hewitt is a design museum. We are a museum that traffics in things that are mass-produced, that are out there in the real world collecting stories and having experiences in the mess of history's past and the present's unevenly distributed future. We are dealing with things that, ultimately, are most interesting in their reckoning.

One name for this phenomenon is fan fiction. I like to think of fan fiction as another kind of random access for collections. Like Galleries try to be for Flickr.

Herge's Adventures of Tintin are now considered masterpieces of their genre and proper culture. It’s worth noting though that while they are many things one of them is very much a mostly benign fan fiction riffing off entire cultures. Take a moment to review the catalog of Tintin's journeys and tell me I'm wrong.

If there are any Canadians of a certain age in the audience they might, like I did, be looking at this book cover and wondering when Herge wrote a story about the Meech Lake accord.

And yes, occasionally things like this will happen although I happen to think all the furor over this painting exposes a pretty glaring double standard.

When this story first surfaced, initial reports suggested that an otherwise insignificant painting had been defaced but then those reports suddenly morphed into shock and outrage when it was discovered that it was actually someone failing in a pretty spectacular fashion at restoring – of faithfully mimicking – the original work of art.

The only thing that changed between those two reports was an awareness of intent.

So we can certainly criticize Cecilia Giménez's lackluster representational skills but it's not like this was really an affront to all of cultural heritage. This was just someone seeing the tree fall in the forest, for once.

In the same way that the Mona Lisa might as well be a photocopy for all that anyone can see it underneath all that protective glass and its carefully guarded buffer zone the Ecce Homo has become a proxy for a whole set of debates about the role and value of cultural artifacts and our relationship with them.

Ecce Homo has, in the end, become a capital-T thing by virtue of all the attention and there are stories that the artist (can we call her that?) is asking for financial compensation commensurate with her role.

My friend Dan Catt made these postcards and you have to wonder whether he's going to get sued for image rights violations, now.

If there's anyone who's not sure what they're looking at here, it's a screenshot of the list of some of the places a person might check in to (on foursquare) near a gas station in California's Central Valley.

This kind of thing happens, literally, everywhere now. In New York City they're obsessed with the Rapture and the End of Days at the moment. Everything is in an opportunity to be -pocalypsed.

This is interesting to me because it demonstrates the ways in which people are expanding the surface area in which to think about place. They are still thinking about a physical and social geography just not one limited to administrative boundaries.

I believe strongly that at the end of the day our goal is to get people in the building. Because the real things continue to possess qualities that their digital proxies do not and can not.

But those proxies are important because they are, like the shadow places that people create online and off, a more expansive surface. They have affordances and opportunities that the delicate and precious things we collect do not.

They are the scouts we send out to imagine how we might see the past in the future.

They are how we rotate our collections. Or at least, in the absence of consumer grade robot warehouses being readily available, they are a design fiction and way of thinking about how to tackle the problem of our collections calcifying into little more than character driven franchises.

We start to do this by simply pledging to ensure that they are present and accounted for on the network but also by being willing to entertain what happens when those resources start to be re-imagined.

In that way our opportunity is not simply to be an archive or a record or a lens on past objects but also a surface with texture that can accumulate the many fictions that the present tells itself about its history.

At this point I pretty much ad-lib-ed the rest of the talk. I wasn't sure how much time I was going to have spent getting to this point in the talk. I would have been comfortable stopping here and decided that if there was time left I could get to in to some more specific examples.

I talked about the social issues involving community participation and the Built Works Registry and the notion of more-or-less relevant contributions. I talked about the fact that all this non-yet important fluff – all the stuff that seems like noise drowning out the signal right now – is actually an amazing opportunity to collect and gather and simply keep safe the stories that might help to explain the inevitable OMGWTF moments when the people who come after us look back in time. That we have an opportunity to stop knee-capping the future.

That we are in a unique position to do these things because of the social contract, the trust, we enjoy with the communities we live in.

I talked about one possible future for archiving Flickr that would see a Library of Congress style insitution (or institutions) running a copy of Parallel Flickr. First to archive the Commons but then to ask all the people who've left a comment, or tagged one of the photos, or just otherwise been involved with the project if their photos can be included in the archive. There's a little bit of hand-waving in that one since we never gave people a way to automate sending messsages to one another on Flickr. Details...

And maybe extending it out by another degree of connections. To think about considering all those other people as the context in which the Commons can be understood. To think about all those baby photos and crooked landscapes shot from moving cars as the fuzzy edges of the air that all these important

works breathe.

The important wrinkle here is that the institution running the archive would pledge to continue using Flickr as a single-sign-on provider and to honour the relationships permissions around all those photos. And that if the worse were ever to happen, and Flickr wasn't around anymore to validate a user's identity, that any photo not already public would immediately go dark

and the so-called 70-year clock would start ticking. That those photos would vanish from sight for a set amount of time to protect the innocent but with a means for eventually bringing them back in to the fold.

A quick shout-out to both George Oates and Jason Scott with whom I've long been tossing around the problem of archiving something as big and as squishly and as complex as Flickr and whose ideas and sensibilities are all over this proposal.

I talked about the fact that delivery and inclusion in our historical collections are becoming increasingly intertwined and re-inforcing one another. I didn't talk about artisanal integers but I probably should have.

I used the time as an excuse to the show something by a New York artist named Jilly Ballistic whose work I have yet to see in the flesh-y reality of the city's subway system but that I stumbled on, one day, while poking around Flickr. Because (s)he is awesome.

This blog post is full of links.

#otaku