the elephant in the room: build it or buy it?

These are my slides from the Bring Your Own Device and In-Hand Interactives: How Covid-19 Forced Innovation in Our Interactives session at the MCN 2020 (virtual) conference. I was paired to present alongside David Zlatic from the Cincinatti Museum Center. I didn't know David before this event and we spent the months leading up to our session getting to one another and talking through the issues and our experiences with them. Whether or not our session was a success it was a delight getting to know David in the process. This is what I said.

I'd like to start with a riddle.

But no one can do anything about it.

Is it really there?

I'm starting with this riddle because the question of how digital initiatives are funded, whether they are budgeted as one-time capital expenses or ongoing operational expenses, is where most museum-related technology discussions end up. This is especially true of discussions about whether to "build or buy".

I mention this because I think it is the root cause of so many of our challenges trying to do anything labeled "digital" in the sector. A lot of what I am about to say crashes up against some uncomfortable and unpleasant realities about the way the sector operates. I am not going to answer the op-ex versus cap-ex problem today but I also think it's important to admit it is real and present.

My own feeling is that, in practice, capital projects are strung together for years on end to the point where they are functionally indistinguishable from daily operations.

They are capital expenses in name only.

The day-to-day reality is that they are essentially operational expenses but with the luxury and caché of larger budgets and none of the responsibility or hassle of actually operating anything or of managing the people necessary to do so.

This bothers me because it's money that could be better spent by hiring people, and then being able to afford to keep them around, to build and nurture the kinds of digital initiatives that the sector says it needs and wants.

It is sometimes said that technology is the connective tissue that binds people. For example we are all able to gather here today because of tools like Zoom and Slack. At the same time people are the connective tissue that bind technologies.

What I mean is that there is a limit to what software can do on its own. At some point, in order to meet the specific demands of a project, someone needs to sit down and write the software that tells all the other software and complex systems what to do. These are the people the cap-ex / op-ex dilemma tells us we can't afford.

If you believe that to be an intractable problem then the rest of what I am about to say will probably sound like someone shouting at the sky.

I believe we can't afford to not tackle the staffing problem because some amount of in-house development is the only way we will make our digital initiatives sustainable beyond any single capital fund-raising cycle.

But there is also a need to change the way we do that in-house, and in-sector, development.

Historically, one of the things that has characterized software projects built to be used by more than a single institution is that they are overly broad. They try to do too much and account for too many customizations necessary to account for too many different institutions. They are too much of everything and not enough of anything.

We need more small, focused tools that don't try to be all things to all people, all the time.

As a very practical first step to finding a way out of the build-versus-buy hole we've dug for ourselves we need to develop a new practice for the way we build the tools we use internally so that they might be split in to smaller pieces that can be shared by as many people as possible externally.

But first... 2020.

One of the things that's happened this year is that the long bet the museum sector has made around touchable surfaces as the principal interaction model for visitors in our galleries is facing an existential crisis. Until there is some resolution to COVID-19 all the touchable surfaces we've invested in are untouchable.

This has led a number of institutions to revisit strategies centered around the idea that visitors will "bring their own device", namely their phones. That's understandable but it doesn't answer the question: How then does a person's device interact with your museum?

If the goal is for a museum to interact with and trigger an individual's device, one it doesn't control, how precisely does that conversation get started, nevermind what happens on that device afterwards? This is the part where we have to stop thinking about what might be possible, in some hypothetical future-world, and instead focus on what's actually within our reach today.

Here's a list of available technologies in 2020 that can be found on most people's devices for triggering different kinds of interactions beyond touch, ranked roughly in order of complexity and sophistication. With the exception of barcodes, which I guarantee you are more complicated than you think, each item in this list is an incredibly ambitious and nuanced ecosystem in its own right.

Ideally, we'd like to be able to have access to all of these things in a web browser so we don't have the burden of supporting multiple platforms or older devices or the hassle of publishing things to an "app store".

But that's not likely to happen any time soon.

Most of these technologies are still entirely dependent on, or often handicapped by, vendor platforms in order to operate and all of them demand significant amounts of time and expertise to configure. There are some exceptions but, by and large, these are technologies that are still only available to so-called "native" applications. This can be a discouraging realization.

What, then, can we learn from the Digimarc experience that David has described?

Briefly, the Cincinatti Museum Center migrated all of their existing in-gallery interactive experiences to a mobile website and used Digimarc codes embedded in wall labels and signage throughout the museum to open those experiences on a visitor's phone.

The first is that I think Cincinatti's decision, in this case, to use a vendor solution was the right one. It made sense given the institutional capacities and constraints. The second is that it points to something the sector needs. It is also something that the sector can and should develop for itself.

Consider what Digimarc does: It embeds an identifier in a photograph that triggers an action or an interaction. In 2020, this is actually the kind of thing that we could build by and for ourselves. We don't even need to embed anything in a image so much as simply be able to recognize an image and associate it with an identifier.

Importantly we don't need to do this for all the possible images in the world only for the images that we want to include in our wall labels or our signage. We don't need to see all things we only need for certain things to be minimally viably recognizable. This is well within the capacity of a handful of institutions to develop and everyone else to use and improve.

Just as importantly, I am not suggesting that we write software to replicate Cincinatti's in-gallery experience.

I am talking about the ground-level functionality of using an image as a trigger for subsequent interactions, to bridge a physical space with its online counterpart that a visitor interacts with on their device.

I was part of the team at the Cooper Hewitt that designed and launched The Pen. The Pen was an interactive stylus with an embedded NFC reader that allowed people to collect objects on display by tapping their pen to a wall label which contained an NFC tag with that object's ID embedded in it.

At its core the Pen was about making every object in the museum addressable and of broadcasting that address in order that a variety of applications might do something with it. That was the ground-level functionality from which everything else was derived.

We invested a lot of time and money in the Pen but it was always possible to implement the same functionality using the Cooper Hewitt's API and an Android device, which have supported reading NFC tags since well before the Pen was launched.

We invested in the Pen partly because it wasn't possible to scan NFC tags on iPhones in 2015 but principally because its design promoted particular kinds of behaviours we wanted to encourage in the galleries. Specifically, we wanted people to understand that they had license to interact with the museum and to have a "heads up" visit, and not spend all their time looking down at their phones.

But we also went to great lengths to ensure that the underlying functionality of the Pen, that each object was addressable and broadcast its address over NFC, remained open and untethered from our own very opinionated application of that functionality.

Like a lot of museum interactives the Pen was promptly removed from the floor in March of this year as a precautionary measure to prevent the spread of COVID-19,

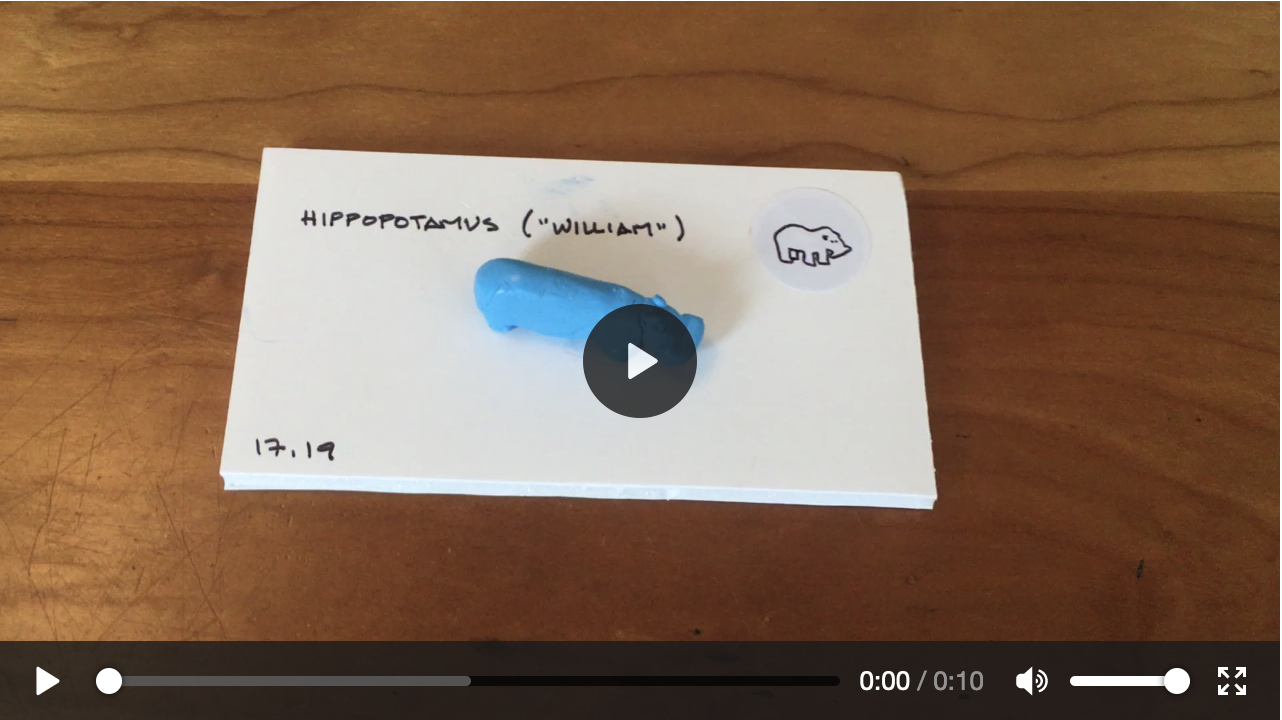

Around the same time I got my hands on an NFC-enabled iOS device (they finally exist now) and decided to see whether it would be possible to implement something like the Pen as an iOS application. Here's what that looks like, complete with spelling mistakes because I filmed this demo before finishing my first cup of coffee.

Once I got an iOS application working for the Cooper Hewitt collection I decided to see if I could use it with another museum's collection. This is a video of me using my "bring your own Pen" device to collect objects from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Met doesn't have NFC tags embedded in their wall labels so this might seem like a purely academic exercise but it does prove the point that this an interaction model which is not bound to any single institution or experience.

I mentioned that all of this has been possible to do with Android devices since the end of 2010. It's also possible to program Android devices to act as though they are dynamic NFC tags. This is a short video showing an application that publishes a new NFC tag containing the current date and time every second, being read by an iPhone.

The Met doesn't have NFC tags embedded in their wall labels. Most museums don't either. SFO Museum, where I work, places most of its wall labels on slanted rails six inches behind glass. Even if we wanted to put NFC tags in our labels no one would be able to read them because they would be too far away.

So as I've been thinking about this idea of minimal viable addressability I started to think about other ways that an object might broadcast its presence.

This video show two phones, each running the "bring your own pen" application. The phone on the left is configured to display a random object from a variety of museum collections and broadcast that object's identifier as a Bluetooth Low Energy advertisement. The phone on the right is configured to read tags and collect objects, as usual, but instead of trying to read NFC tags it looks for and reads Bluetooth Low Energy advertisements.

None of this is really about specific technologies, like Bluetooth or NFC. It's about thinking of ways that things are addressable. It's also not about what happens with those identifiers. As you can see this application doesn't do very much. It is about identifying and packaging the technical plumbing necessary to enable the basic interactions, the first steps, that we need to do everything else.

Before COVID-19 SFO Museum was working on its own touch-based interactive application, to be deployed in the terminals.

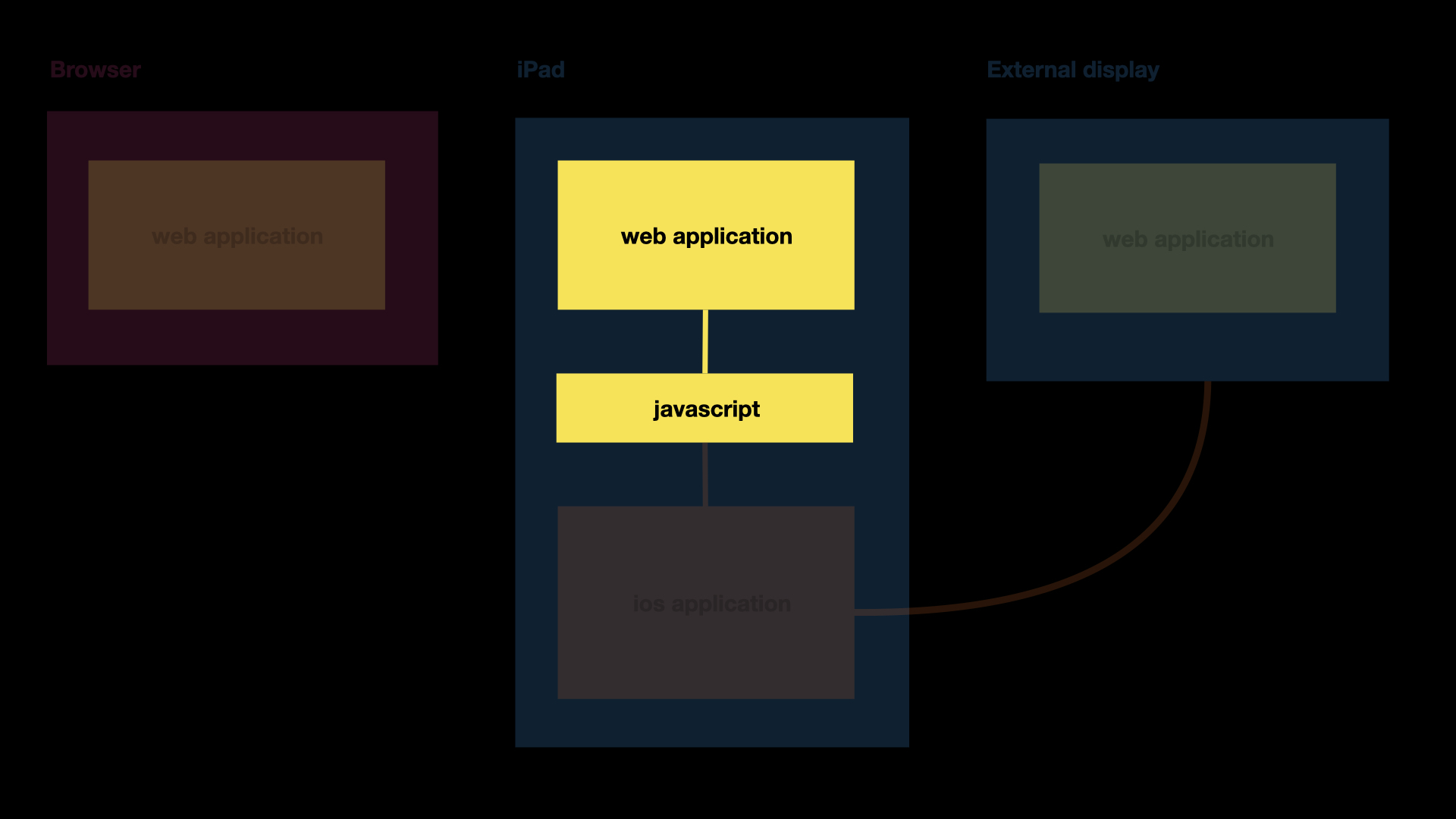

It's a plain-vanilla web application that is run inside of a native iOS application running on an iPad and mirrored to an external monitor. This is a pretty common pattern for a lot of applications so we're not doing anything revolutionary here.

We opted to wrap the web application in an iOS application, rather than using a cross-platform framework like Cordova or Electron, because there are still a few things that can only be done natively. In our case: Displaying, and syncing, different content from the same application on two different screens.

Here's a simplified view of what that looks like. Do you notice the yellow box marked "javascript" in the middle? I'll come back to that in a moment.

There are two important reasons for developing the application itself using web technologies. The first is the ease and speed of development and being able to test things in a web browser. The second is that we know that whatever else happens in Apple's ecosystem our application will still work in a web browser. In fact the guts of this application are already part of our website.

These boxes, which are all the same web application, are really the only SFO Museum specific parts of what we've been developing.

In iOS, there is a bridge for communicating between the web application and the native application using JavaScript. For example, the application I've been describing is also meant to run offline so we using some native iOS functionality to make that possible.

Our goal is to treat this as a fast, cheap and reusable template for building interactive installations.

I am fond of telling people that we have a developed a system for interactive displays with minimal hardware and stable costs, that works both online and offline, and that we can deploy to any four-by-four foot space at the airport.

The only question should be: What do we want the next interactive to do?

It's worth mentioning that what's interesting about this isn't so much that it's an iOS application or that it's running on an iPad. There are specific reasons why we chose these platforms but the same thing could be done with others. What's interesting to me is a model for developing sophisticated interactive applications and identifying the separation of concerns between the applications themselves and all the plumbing necessary to run them.

We're planning on open-sourcing this work sometime next week.

In 2020, the problem with deploying iPads in a public setting is that no one wants to touch them. If people can't, or won't, touch an iPad where touch is the principal means of controlling an application is there really an application anymore?

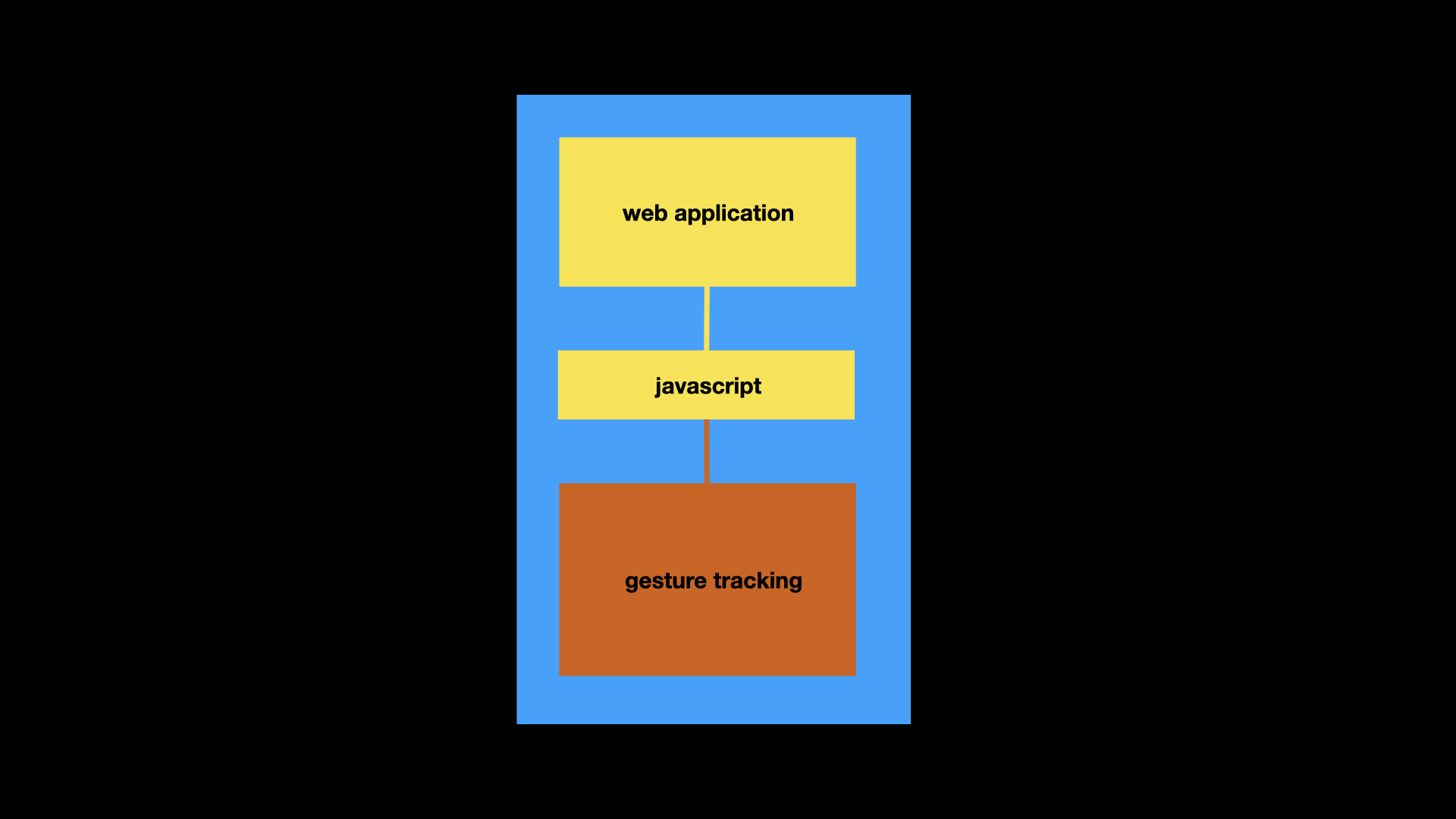

At SFO Museum we have started to experiment with gesture controls, using the built-in motion-tracking functionality that has become available since the release of iOS 14. Software systems for gesture controls have existed for a while but they are often complicated, expensive or both. What's different here is that they come preloaded in the operating system now.

The previous application I've been discussing has some pretty involved interactions so we're starting with something a lot simpler first. We are starting with a basic gallery application and working to add rudimentary next and previous gesture controls.

It's early days still, and there are lots of bugs left to fix, but we've proven that it can work.

The video I just showed is a native iOS application but our plan is to create a hybrid application, similar to the one I showed before, that will allow us to use native iOS code to track basic gesture controls and then use the Javascript bridge to relay that information back down to a bespoke web application.

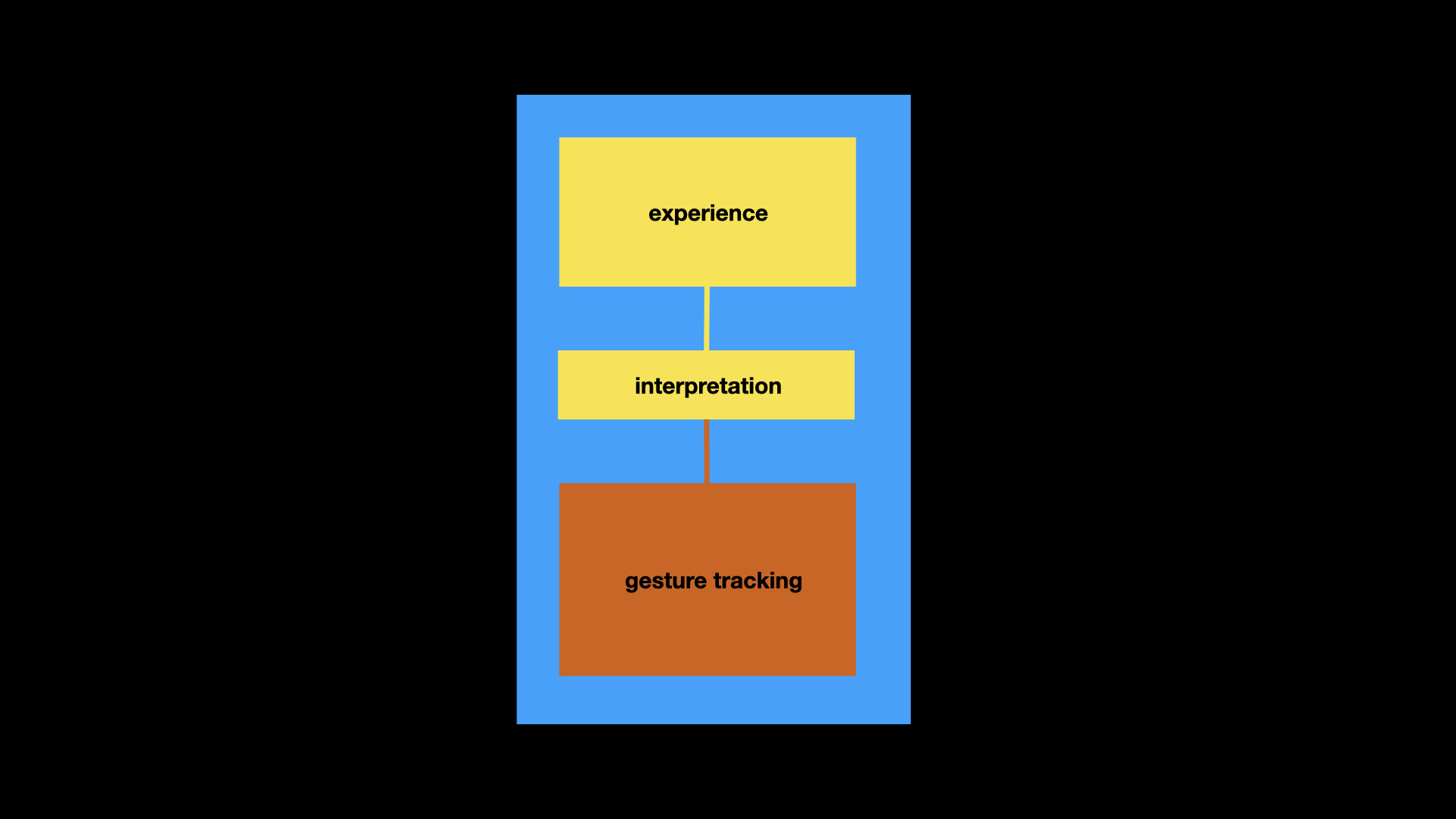

Here's another way of looking at that same model.

The point I want to make is that things like gesture controls are complicated enough, all on their own. They only become more complicated the closer you get to the implementation details and that complexity is multiplied again by the demands that each museum's unique needs and requirements place on things.

Here's another way, still, of looking at that model.

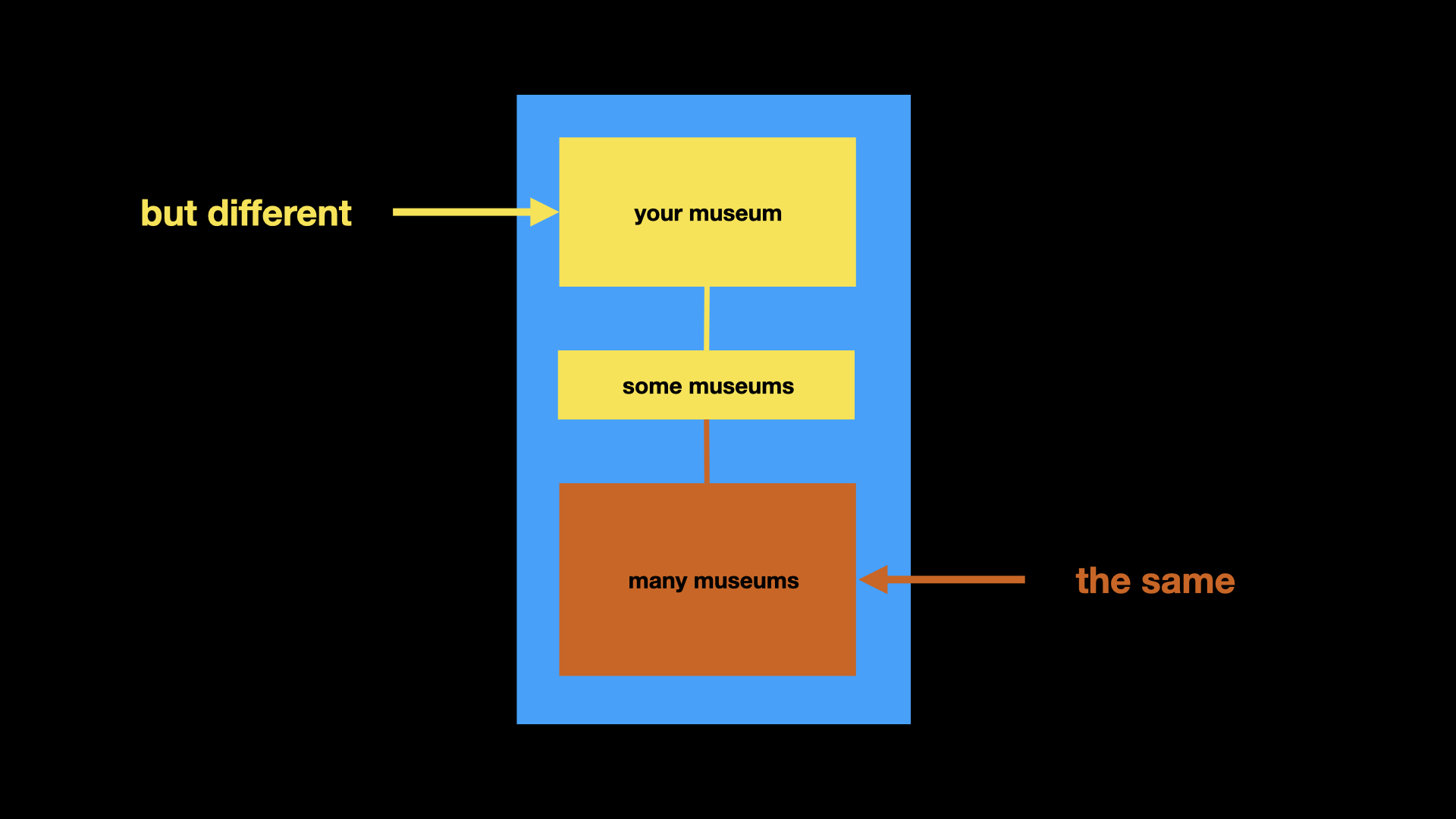

The yellow box at the top is your museum. Your museum is unlike any other museum. It is unique and that character is captured in the expression of its experiences.

The yellow box in the middle are the few places where there is actually overlap, interpretative or otherwise, between institutions.

The stuff in the orange box, in this case gesture tracking, is the common ground that we are all building on.

The things in the orange box are the standardized materials that we all use to make things possible. You and I may have very different houses but they were probably both built with two-by-fours.

Those two-by-fours are the orange box.

The argument I am trying to make is that when we, as a community, have tried to develop shared infrastructure we have spent too much effort trying to work around the yellow box at the top of this stack and not enough on the orange box on the bottom.

If we're going to try and pool our resources then we are better off focusing on the things that look like two-by-fours than our respective homes. This was already a problem before COVID-19 but it's so much worse now that our principal means of interaction – touch – is limited or entirely unavailable to us.

We are faced with the prospect of replacing that model using complicated technologies that don't enjoy the same maturity or levels of deployment and facility that touch-based interactions do. We are being asked to do these things at a moment where the time and budgets do to them are in short supply.

Throughout this talk, I've been trying to demonstrate two things:

One is actual working code implementing alternative approaches to an interaction model we can no longer take for granted. A lot of it is rough around the edges. That's not on purpose but it does serve to highlight the idea that we need to get used to sharing, evaluating and contributing to work in progress.

Second, a practice of doing the extra work to enforce strict separations of concerns in our applications so that we might better identify, extract and share common pieces of functionality where they exist. This is the crux of my argument.

No one has the time or the capacity to support the full weight of anything other than their own museum or institution. But maybe we have just enough time to grow and nurture a common kit of parts that can be re-used and adapted by and for individual organizations. It may be too soon to imagine that we can make everything easy but maybe we can start to make more things at least possible.

I recognize that many institutions don't have the staff to do any of this work yet. That is why I started with the cap-ex versus op-ex riddle. That is the larger question we need to solve, in whose shadow everything else sits.

A lot of what I've been talking about is aimed at institutions that do have technical staff. I want those of us who are able to support technical staff, whether it's one person or a dozen people, to work to improve the way we do things. I want us to do this in order to demonstrate to the rest of the sector, and in particular to the boards and directors of institutions who are skeptical of the value of in-house staff, that it is worth building things ourselves rather than always buying from someone else.

Thank you.

This blog post is full of links.

#mcn2020