be the diorama you want to take a selfie with

Last week I had the pleasure of delivery the opening keynote for the Conference on Mobile Position Awareness Systems and Solutions (COMPASS), organized by Claire Pillsbury, at the Exploratorium in San Francisco.

This talk felt like a bit of tightrope walk and I was very conscious of not wanting it to fall in to a series of cascading tangential rabbit holes, which would have been easy. I made an effort to keep things curt and direct so much so that my sense of how long the delivery would take was completely off-base and the talk was over sooner than I expected.

If I ever have the chance to do this talk again there are a few places that would benefit from a longer discussion and I've tried to update the text where necessary. In the end people seemed to enjoy the talk and it seems to have had its intended effect to serve as a lingering (but friendly) echo throughout the rest of the conference proceedings.

To be honest I was so concerned with the pacing of this

talk that when the conference organizers didn't do the usual

introduction with credentials (So and so worked

at...

) I completely forgot to fill in those

blanks myself.

I think I got up on stage and said something like: Hi,

my name is Aaron. I know some of you in the audience. These

days I work at the SFO Museum...

as if that explained much of

anything. For the benefit of my future-self or if you are

reading this weblog for the first time this is what I should

have said:

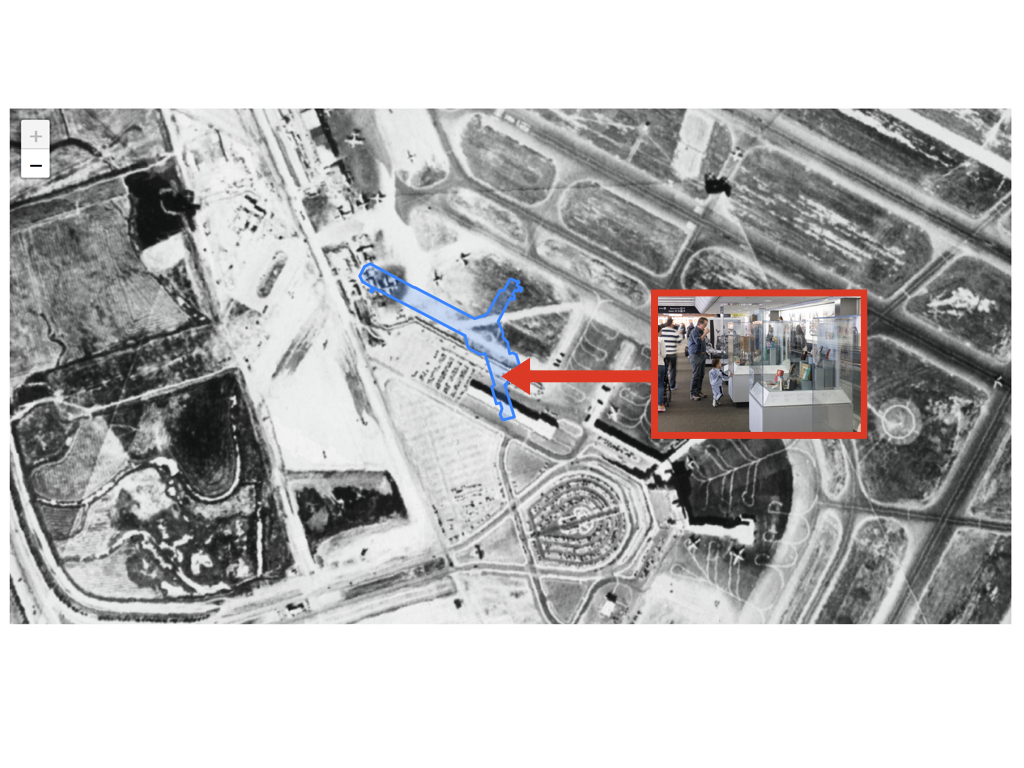

Hi, my name is Aaron. I am the Head of Internet Typing at

the San Francisco International Airport Museum. As silly as a

title like that may sound (and I actually have an even more

vague and opaque official title for HR purposes) it is the

best way to describe my role at the museum. I am charged with

wrangling this crazy little thing we call the internet

in the service of a nearly forty-year old museum with a

permanent collection of over 100, 000 objects that has

produced 1,200 exhibitions across 50 gallery spaces. My job is

to make all of these things visible, legible and approachable

in an environment where few people expect to find a museum (an

airport). In the past I have been part of the teams at Flickr,

Stamen Design and Mapzen where the common thread has been maps

and location. I was also intimately involved with re-opening

the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum in 2014 and

launching the Pen which has a little something to do with

indoor location in museums. Thank you, to the organizers, for

inviting me speak and thank you, in the audience, for coming to listen.

A few years ago before I started working at SFO I did a talk where I argued that the museum sector could learn a lot, at least from an operations perspective, from airports. I am not going to revisit that discussion today except to say that when it comes to the future of indoor positioning and locative technologies museums would continue to benefit from looking at what's going on in airports.

These days I have daily exposure to a long list of airplane and travel industry trade publications. If you look past the hyperbole it is possible to see the near-future of consumer-grade location and tracking technologies being deployed to a mass audience.

I am going to skip the laundry list of examples and

just mention that if Apple's Pay with your face

ad

campaign has ever left you feeling uneasy you might want to

buckle up because it's probably going to get a lot weirder

before it doesn't.

Airports can be distinguished from museums by the volume of traffic they service and the security demands placed on them. This means they enjoy larger technolgy budgets and, generally, fewer questions about consent so it's not always an apples-to-apples comparison.

Still, an aiport remains a useful space to watch technologies being introduced and normalized (or not) and can serve as a guide for museums.

Today I would like to use the opportunity of standing up here delivering the opening keynote not so much to discuss the specifics of indoor technologies (we have the next two days for that) but rather to use these technologies that enable the work we do as a lens back on to that work itself.

I would like to ask some questions, awkward questions even, that do not have ready or easy answers. I want to ask these questions with the hope that even left unanswered they may serve as a useful foil for the rest of the conference.

What I mean to say is that using Disney as a frame of

reference when discussing what is possible in the museum space

in 2018 is an unhelpful distraction. Saying But Disney does

it...

has become the trickle-down economic theory of

technology development in the museum sector.

It also does a real disservice to the genuinely hard work these companies have done and continue to accomplish. Google and Disney exist in universes of their own creation, complete with air that we don't breathe, but it is important to recognize that they have (mostly) earned it.

It is important to recognize that there is a network effect in each of their individual efforts and that those efforts play themselves out over multiple projects often spanning years and many failures. The museum sector, both individually and collectively, remains unable or unwilling to make those kinds of investments or to take equivalent risks and the results are predictably un-Disney-esque.

I wish the museum sector would endeavour to create Disney-scale infrastructures and tooling in service of cultural heritage. Until it does though maybe we can just admit that talking about Disney does nothing to address the needs and concerns we face on a day-to-day basis?

A few years ago my former colleague Seb Chan and I were speaking to a Large Museum about their digital initiatives. After we left Seb commented that the last thing they, or any museum, needed was another in-gallery recording booth for telling personal stories. Not because the stories aren't interesting or important but because a museum is often the wrong place to tell them.

People may not be comfortable telling the stories in a public space or, as often as not, people don't feel a story they know is theirs to tell. Museums would be better off, Seb suggested, in setting up phone lines and answering machines and letting people call in at some later date.

In another universe we would have built this and I hope one day someone does because it's a genius idea. If you'll permit me to gloss over the not-insubstantial implementation details what excites me about this scenario is that in all these phone calls and stories I see a radio station.

Not a metaphorical radio station but an actual broadcast channel run and managed and, yes, curated by the museum. I see a radio station as a means to encourage community participation and as a way to celebrate and foster a multipilicity of views about, and the nuance that surrounds, a subject.

I see it as a way for the museum to exist meaningfully beyond the walls of the building.

Shameless plug: If you are flying out of SFO on your way home and happen to be flying out of Terminal 3 there is an entire exhibition of radios on display right now. If you are flying international out of Boarding Area G there is a post-security connector to Terminal 3 so you can get to the exhibition that way too.

Another, simpler, take on the idea of the radio station can be seen in some of the work that Shelley Bernstein has done with wearable computers at the Barnes Foundation. This image shows work they did to prototype a watch-based application that will show you stuff nearby, include some sort descriptive text and an image and offer to let you save that object. Personally, I don't actually care about the images and I've never been convinced that low-cost watch-scale hardware could show you more than a handful of images before needing to be rebooted.

What I like about this project is that it points not just to the potential of a future idea but the actual mechanics. These are sub-100$ Android watches which is a big deal because it means that the cost of hardware, which is equal parts a well-designed and robust enclosure as it is electronics or software, becomes a realistic line item in a museum budget.

I definitely don't care that it's a watch. What I like about the form-factor though is that (having removed the wrist strap) it's something you can carry around in your hand or on a lanyard and that can be operated with nothing more than your thumb.

Basically there are two problems that you need to answer when you're working with indoor location in a museum. The first is: Where am I? This is or can be a mostly solved, or solved-enough problem, using techniques like wifi-triangulation. The second more urgent problem is always the same: Now what?

Museums tend to see this as an opportunity to get in front of people and demand all of their attention. What if instead of demanding that visitors constantly context switch between the physical and screen-based spaces the device (the watch) simply allowed you to signal interest in or awareness of an object, offering a minimal amount of feedback.

That a touch-based watch, costing less than 100$, gets you more than half way there is important because there is still a non-trivial amount of engineering making that idea in to a tangible reality you can hand out to visitors. This might sound like a simplified (and way cheaper) version of the Cooper Hewitt Pen and depending on how you framed it to people it could be.

What I imagine is more like a smushing-up of

the Pen and the Brooklyn Museum's Ask

Brooklyn app (and its back-of-house infrastructure and

processes) and SFMoMA's location-aware audio guide application. Specifically something that you carry

around and whether it's through active or passive signaling

generates an audio guide

or a podcast

or a radio program

that you can listen to after you've left the museum. Something

with a narrative that you can listen to while you make dinner,

for example.

Dave Patten, from the Science Museum,

discussed their

experimental Museum Egg

project on the second

day of the conference. While not exactly what I've just

described it is close

enough in spirit and execution that it's not a stretch to imagine. Its size and case design aren't the most elegant

but with the caveat that both miniaturization and enclosures are tasks guaranteed to

make you sad it remains an exciting project.

What both of these imaginary projects share is the goal of giving visitors a reason to come back to the museum. These projects assume that you will miss something the first time through an exhibition. You might miss something because you didn't know to look, you couldn't be bothered to wait or because your kid ran in to another room and then life took over.

They are premised on the idea that in many ways the contemporary museum experience can be as stressful and distracting as it may be enlightening. They are premised on the idea that in many ways museums are bad at being museums.

These projects try to imagine a way to talk about our collections with visitors outside and beyond the museum rather than talking at them in the moment. This is after all the novel change that the internet has made possible.

Now for the awkward questions.

The first question, and the reason I started with all these stories of museums operating outside the building is simply this: Do we believe that most people will ever visit an exhibit, never mind the museum itself, twice?

I recognize that's a fairly provocative statement but I think it's important to admit that it's not a given anymore. It's especially not a given for museums whose audience is predominately tourism-based. Some small number of those visitors will grace a museum's doors twice but the rest of us are just boxes to tick on their selfie check-list.

What does this say about our collections and our work when one of the central tenets of cultural heritage, of the humanities really, is the value and a celebration of prolonged and repeated consideration of a work or a subject?

Are we exacerbating the situation with technology? Are we using all the fancy technology we have at our disposal to create single-use spaces that will never be graced by the same person twice? Are these spaces the disposable coffee cups of cultural heritage?

Or does the technology simply demonstrate that the only common language we have for discussing our work, as museums, with most visitors is spectacle? That is a nice way of asking: Does anyone really understand what museums are trying to say, or why?

Do we celebrate the experiential museum because it's the only place where most people's lives and the language of scholars intersect? Is this mediated and emotionalized half-language the only shared understanding we have left?

It would certainly help explain the success of projects like the Color Factory or the Ice Cream Museum or any of the other amusement parks dressed up as museums that have opened their doors in recent years. Why should we be surprised by their success if their basic outline is everything I've described in the last two slides? They are spectacular one-offs with no shortage of technology supporting and manufacturing a guaranteed experience that typically manifests itself as a collection of selfies.

I find myself wondering though whether in these selfies, and other ephemera like it, we are seeing visitors grasping at straws for something like the contemplative moments we used to say define museums. They are, by and large, profoundly isolated moments but they are something tangible that exists beyond the visit itself.

They afford a revisitation of things beyond first impressions.

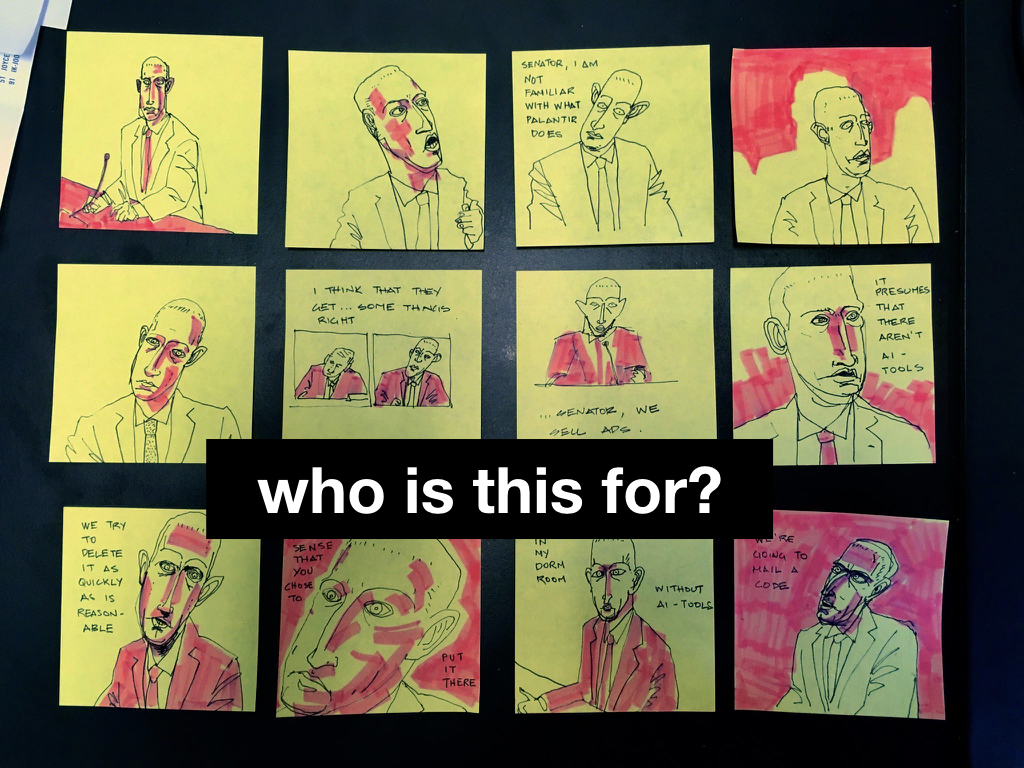

Speaking of revisiting things I want to end this talk with a short discussion about data collection. Some of you may remember that earlier this year Mark Zuckerberg was summoned Capitol Hill to address questions about Facebook's role in the 2016 elections and the general chaos that defines our lives these days.

Zuckerberg's defense can be roughly paraphrased as Gosh,

golly, gee whilikers. We had no idea that people would do bad

things with our platform.

This is an argument that is as

laughable, coming from a company that employs as many clever

people as Facebook does, as it is indefensible.

Claiming a deficit of imagination for how a technology might be abused is not, or should no longer be, an acceptable excuse in 2018.

We have long relied on technological cost and complexity doubling as a barrier against our own worst impulses, both external and internal. We are living through a moment when all of those safeguards are being shredded in front of our eyes by advances in hardware and software and the mountain of data those advances are producing.

The impulse to market, sell or otherwise leverage the data

that we as museums collect through location-based technologies

will be strong even though this has nothing, and I mean

literally nothing, to do with the business

of cultural

heritage. The impulse to develop museum exhibitions solely for

the purpose of collecting visitor data will surely follow, which

assumes someone isn't already doing it.

On the second day of the conference Jen King, Director of Consumer Privacy at Stanford's Center for Internet and Society, did an excellent talk digging deep in the nuts and bolts of these issues. Hopefully she will post her slides somewhere and when she does it should become required reading for anyone in the cultural heritage sector.

All location or positioning technology trends towards identification at the atomic or individual level. If we are going to deploy these technologies far and wide within our institutions then I want to leave you with a final question. It's a question that I think we not only need to ask ourselves but that we actually need be able to articulate an answer for: Are museums going to be more than the carrot to surveillance capitalism's stick?

This blog post is full of links.

#diorama