Everyone is Design Eagle

Way back on July 22nd of 2015 Mike invited me to speak to the Fellows at Code for America about developing and launching the Pen as part of re-opening the Cooper Hewitt and about the experience of doing it inside of Government Club. It's been a busy fall and early winter so I've only poked at fleshing out my slides and notes as time has permitted.

This is, more or less, what I said. There's not a lot about working in Government Club per se. One day Seb might tell the story of trying to push through the contracting side of things but really, we were incredibly fortunte to have people inside the machine

— on both the technical and legal side of things — who believed in the project and helped clear a path for all the remaining work which bordered on insane.

In the end, it took about ten months from the time I did this talk to the time I could say this blog post was finished. During that period I did an entirely other talk that focused on different details but many of the same themes that follow below.

There is no way that I am going to cover everything that's happened at the Cooper Hewitt over the course of a single hour. We could spend all afternoon talking about the last three years that have culminated with the re-opening of the museum, in December, and the launch of the Pen three months later. Instead, I'm going to focus on only tiny slice of the overall project today. I've put together an appendix with a reading list of pieces written some by me but mostly by my colleagues to help give you an idea of the scale and scope of the overall project.

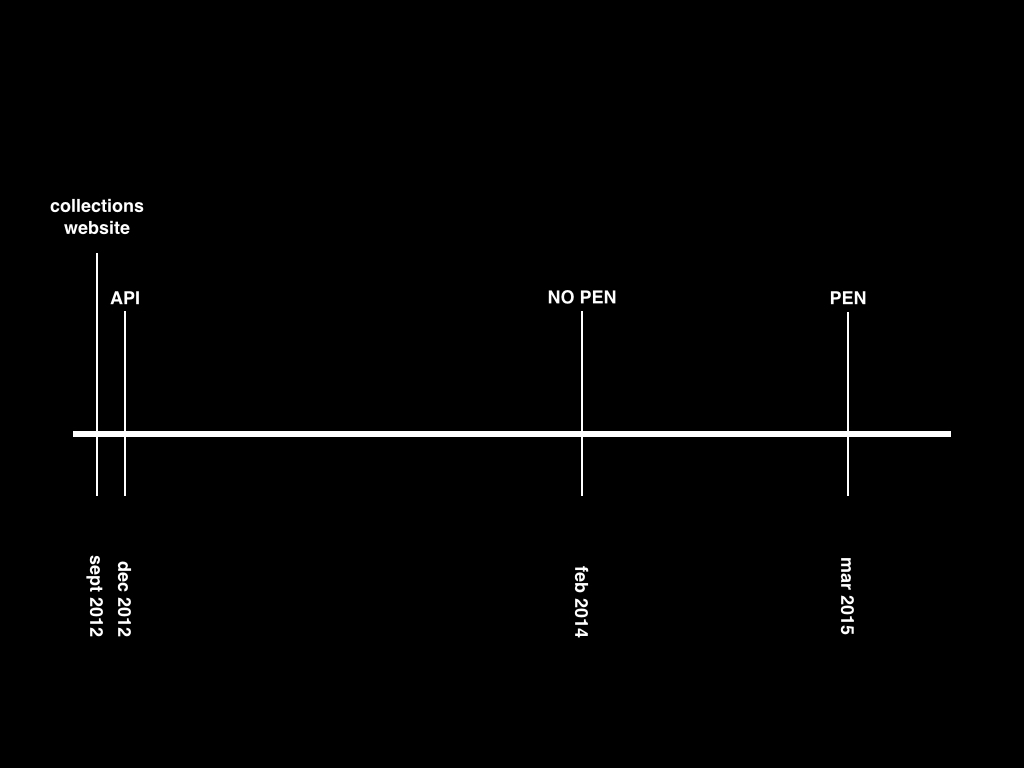

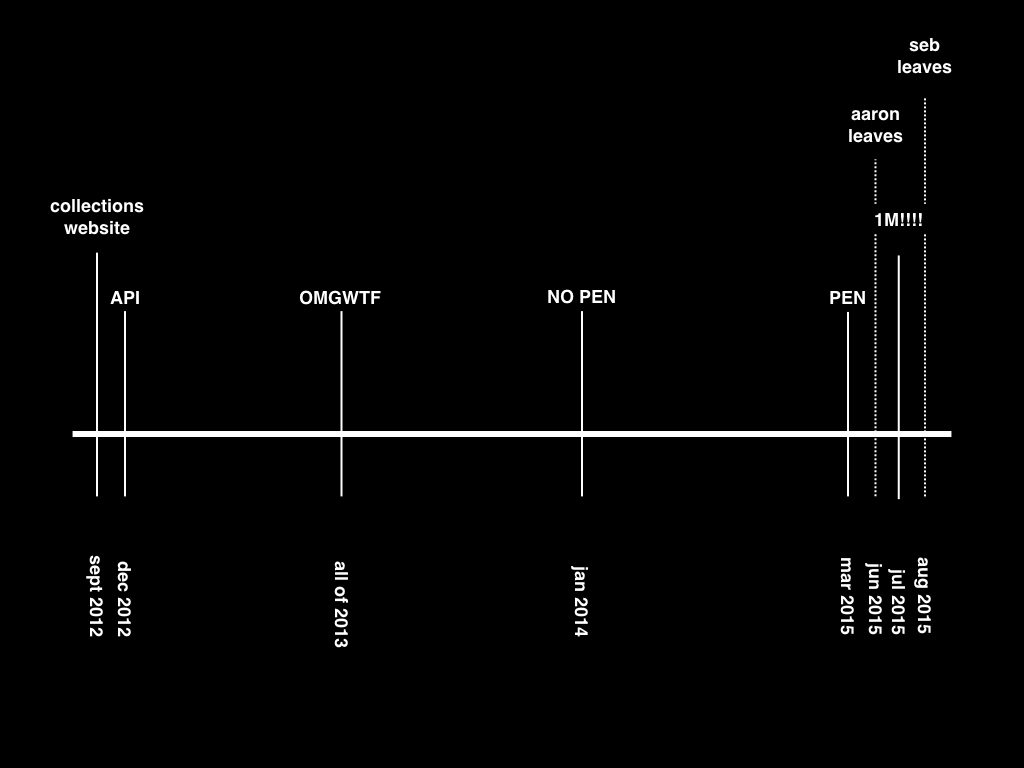

I'd like to start with an abbreviated timeline. This is no way representative of the entirety of the project but it's a good way to highlight some aspects of the way we worked that allowed us to complete the project at all.

I started at the museum in July of 2012. In September of that year we re-launched the collections website under the banner of a public alpha.

In December of that same year we launched a public API for the collections website. It didn't actually take us three months to build out the API scaffolding and dispatch mechanism. It took us three months to decide that it was the right time to focus on that work.

By the end of 2012 it was becoming apparent that part of our work, on the Digital team, was to be able not so much to anticipate the needs of our contractors based on meetings and design proposals but to have an opinion about how those needs would be addressed.

This was not always obvious and made for some difficult conversations. There were moments during the re-opening when we had to say to almost every one of the contractors that their particular piece was only one part of a much larger project.

If you are going to say things

like to people then you also need to be able to articulate

the what and the why of that larger project

and so the API was as much of a tool to help the

museum answer those questions as it was

a service

for our contractors.

In March of this year (2015) we launched the Pen. The Pen is a custom-designed and custom-built interactive stylus with a built-in NFC antenna that allows visitors to collect objects while in the museum and to revisit them later both at the museum and later still on the web.

The Pen actually launched three months after the museum re-opened, in December of 2014.

The thing that you need to understand about the Pen was that at the beginning of February 2014 there was no Pen. There was nothing. There was the idea of the Pen and everything we believed that such a device might make possible. At the time there was what can only be described as a Hail Mary pass, still hanging in the air and which no one expected to land before March, to determine whether the Pen was even possible. Not possible as-in could we get it done in time but possible as-in could it be at all.

Which is to say: By the time we got to the end of 2013 this is what that year looked like in retrospect.

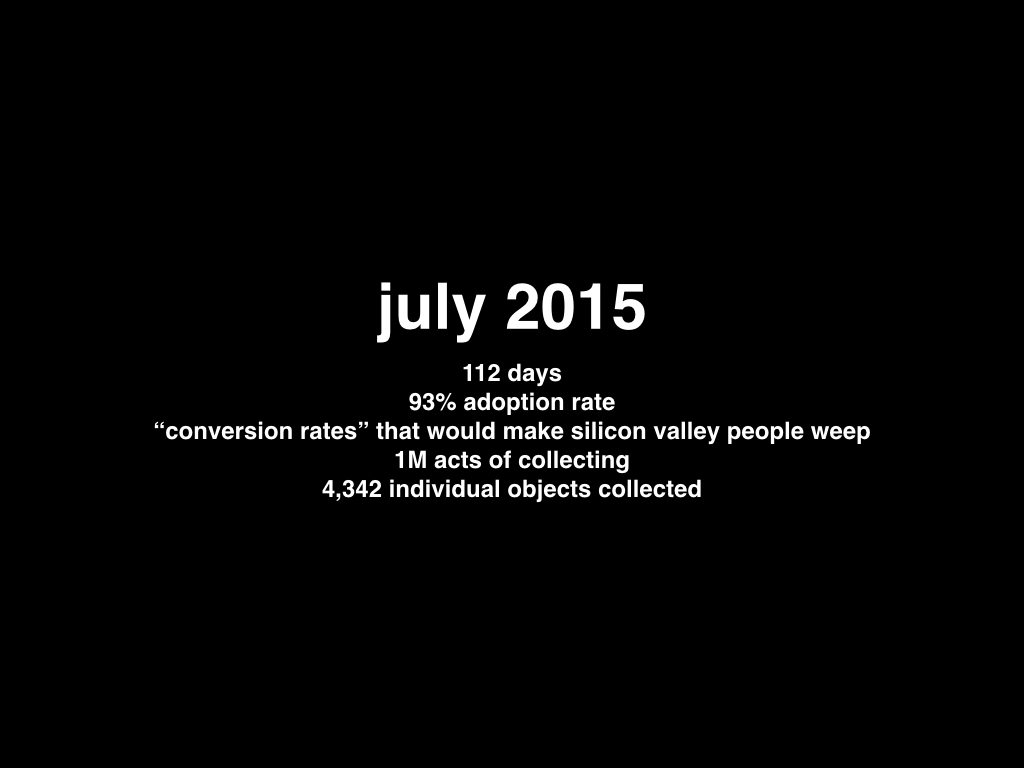

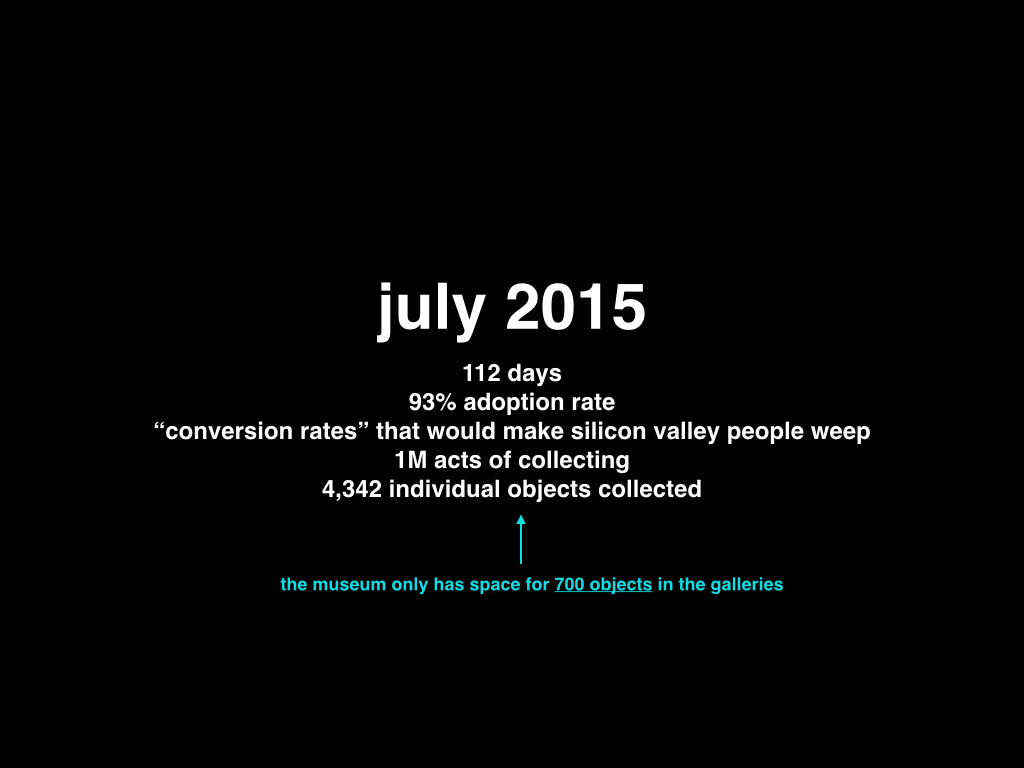

But in the end we did launch the Pen and to everyone's delight and amazement in the first 112 days visitors collected objects with the Pen a million times.

And then finally, in relatively short order, I left the museum in June and next month Seb Chan will also leave the museum.

I include these dates not because Seb and I are so awesome that it's worth noting our departure but because our leaving is, in my mind, an important measure and success of the work we've done. I'll come back to reasons why at the end of the talk.

That is a lot to happen in just three years. But it's important to point out that for some people at the museum the project had been going on for a much longer time.

For some people this was only the tail-end of a nearly ten-year project that began with fund-raising starting as far back as 2006 and started getting crazy when the museum officially closed its doors in 2011.

But we didn't just close the museum. We closed the museum in order to do a major historic restoration of Andrew Carnegie's mansion, where the collection is display. This meant both tearing the entire place down to studs and posts and cleaning all the wood paneling with Q-tips but also converting the former offices in to sixty percent more gallery space. Which in turn meant moving the entirety of the permanent collection offsite in order to convert the previous storage facilities, located next door in the townhouses Carnegie built for his daughters, in to office space. If that weren't enough we also planned to re-open with seven to ten new exhibitions launching at the same time, a goal to dramatically increase visitorship and this crazy idea to create an entirely new digital

department inside the museum with a mandate to imagine what it means for a museum to be genuinely part of the Internet and vice versa.

And then in August 2012, the museum's Director Bill Moggridge died. It would be another nine months before a new permanent Director was chosen during which time we all had to carry on trying to understand a vision that I doubt even Bill had fully articulated all the while not necessarily knowing whether it would be a direction a new Director would want to continue pursuing. It all worked out in the end but it's difficult to overstate the impact these kinds of uncertainties can have on a project like ours, especially in the early stages.

Sometime during all of this, I saw an interview between Kevin Slavin and Jack Schulze, still then a Principal at BERG Design in London. At one point, I think while they were talking about the long and difficult effort to turn the studio's Little Printer from an idea in to a prototype in to a genuine commercial project that people could buy with cash dollars, Schulze said: Sometimes you have to create belief.

What I took him to mean is that sometimes the work of creating a novel thing is as much about making people believe that such a thing might even be capable of existing as much as the work of finally crafting it in to being. I scribbled that quote on a note and stuck it to my monitor where it stayed for the duration of my time at the Cooper Hewitt.

There was this one slide.

In the summer of 2012 the museum gave its exhibition designers license to try and imagine what an interactive museum experience for visitors might be outside of just another mobile device or "app". They came back the idea of giving every visitor an interactive pen. The pen would be a device that would give visitors permission, both literally and metaphorically, to actively engage with, to do something in the museum. The pen would be a device that visitors used to browse, to create and to manipulate objects on multi-user interactive tables throughout the museum. They could just as easily have used their fingers but the pen would make concrete the idea that design was about process and doing and that, as importantly, a design museum was too.

The pen would also be a device that would allow visitors to collect

objects on display, or related objects from the collection, and store them in a virtual scrapbook for later retrieval.

It was design fiction in the purest sense. It was just enough of tomorrow — so nearly possible but just out of reach — to reel the museum back to today — the tyranny of realistic expectations or at least budget — in order for everyone to settle on yesterday — work that could be largely completed on-time and on-budget from an existing stack of software components and strategies. Which sounds a lot harsher than it really is.

This is how all client-services work and it is how these companies stay in business and there is nothing inherently wrong with the practice.

The probem for the exhibition designers was that what this design fiction suggested — the ability to provide meaningful and reliable recall for a museum visit — turned out to be something the museum really really wanted. The problem with clients who really really want something is that you need to be able to really really convince them that something is really really too hard.

In the end the whole project turned out to be really really hard but I think the fact that the museum was so dogged in pursuing the idea is a testament to how really really good the idea was in the first place.

This is a video (100MB) the digital team made, early on in the process, to try and help the rest of the museum understand the potential of what was being proposed. This was really important because there was no prior art

or experiences that we could point to and compare this project to.

There's a thirteen thousand word paper about that so I am not going to talk about those details, here today.

Instead, I want to dig in to the details of just one aspect of the Pen that doesn't get a lot of attention because it seems a bit unromantic but without which the whole project would have failed.

Simply getting the Pen manufactured and out the door was hard enough but remember this was only a slice of the overall problem we needed to solve. Early on, we made a series of decisions about the Pen:

- Every visitor would be offered a Pen when they purchased a ticket.

- Visitors would not be asked to give up a credit card or a piece of ID in exchange for the Pen.

Easy, right?

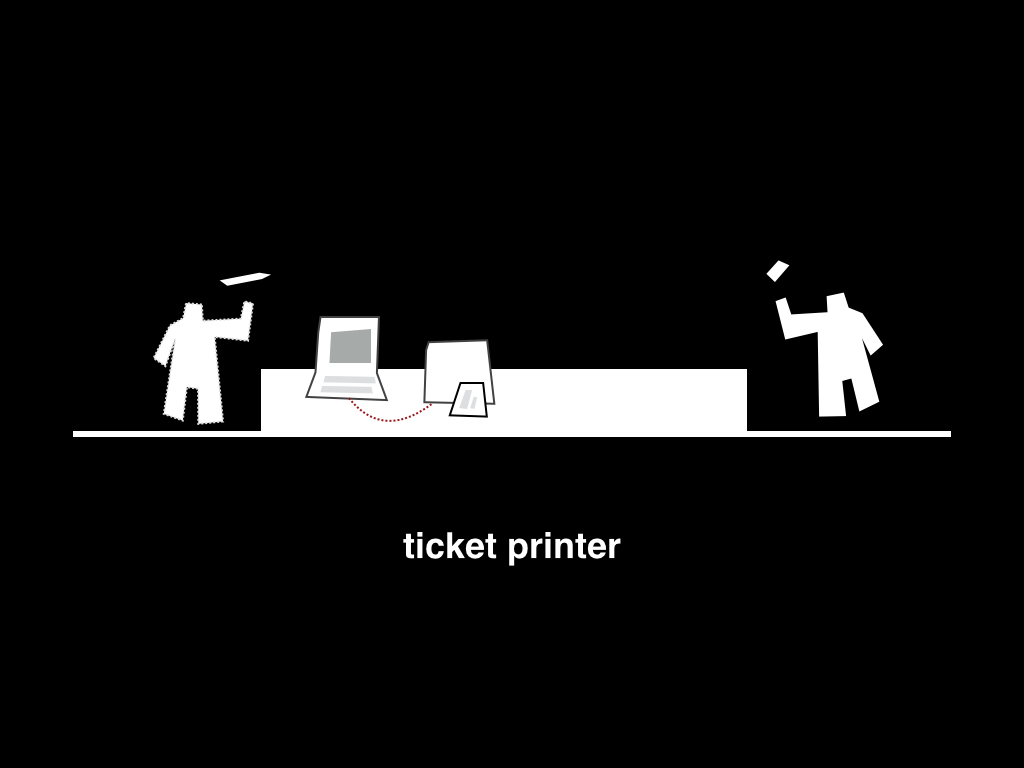

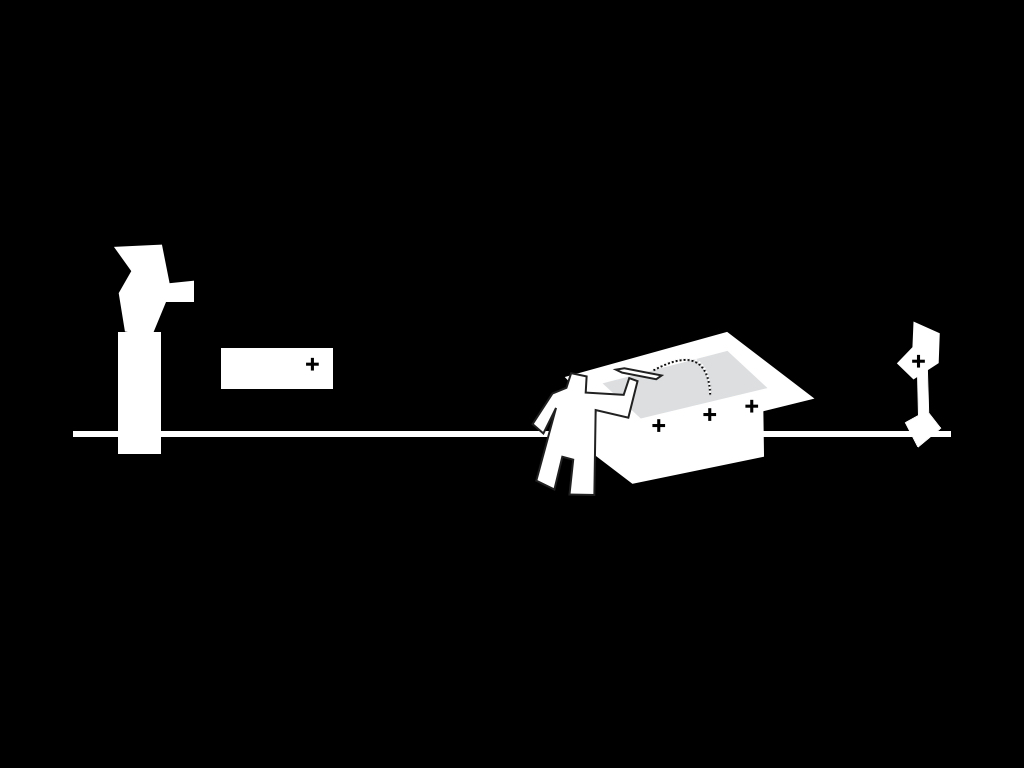

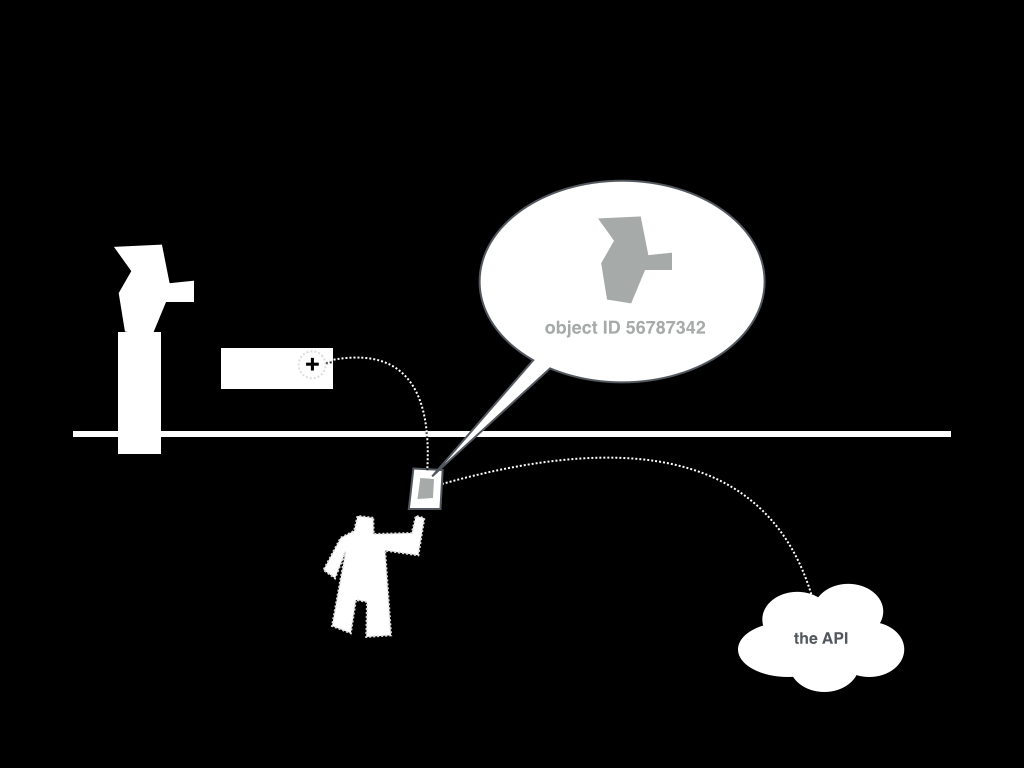

Let's imagine this is the visitor services desk where you purchase, or validate, your ticket to enter the museum. On the left is museum staff, holding a Pen. On the right is a visitor, holding a ticket. In between is a desk and a computer running the ticketing software. So far, so good.

Next to the computer running the ticketing software is a specialized printer for printing the tickets.

Next to the specialized printer for printing the tickets is a barcode reader. There's a barcode reader so that the museum staff can scan a specially crafted barcode on each ticket that encodes the unique ID for that ticket.

There's a barcode reader next to the specialized printer for printing tickets because it (the barcode reader) is plugged in to a tablet computer running a web application.

The web application is communicating wirelessly

with another piece of hardware, called

the registration station

, that's also sitting

on the desk. The registration station has an NFC

antenna plugged in to it. After a ticket is scanned

by the barcode reader the web application will send

the value of the barcode to the registration station

and prompt the visitor services staff member to tap

a Pen to the antenna, at which point that ticket will

be associated with that Pen.

This set-up is the same for each of the three ticketing stations at the front desk.

You might be thinking to yourself: Hey wait a minute... didn't you just say there is a whole other computer that's connected to the Internet with USB ports sitting on the desk? It's a good question. We asked the same thing.

Aside from the fact that the ticketing software is a large and complex system that didn't lend itself to either the functionality or the speed of iteration we required there is another added burden. The ticketing system manages money and personal information both of which the Smithsonian treats as highly sensitive information so all of that happens on an entirely other network than all of the other stuff in the museum.

These so-called registration station are basically just API clients invoking private methods managing the relationships between pens and visits and tickets.

When we first started working on integrating the Pen with the normal ticketing process we hired Tellart, a design studio from Rhode Island, to build and design the hardware, the software and the user interface for the registration stations. Very quickly though we revised the terms of the contract such that the museum would manage the UI work as a web application that would communicate with the registration station using a simple messaging protocol.

This decision saved us when almost as soon as the Pen was launched we realized we needed to make substantial changes to the user interface design of the registration stations.

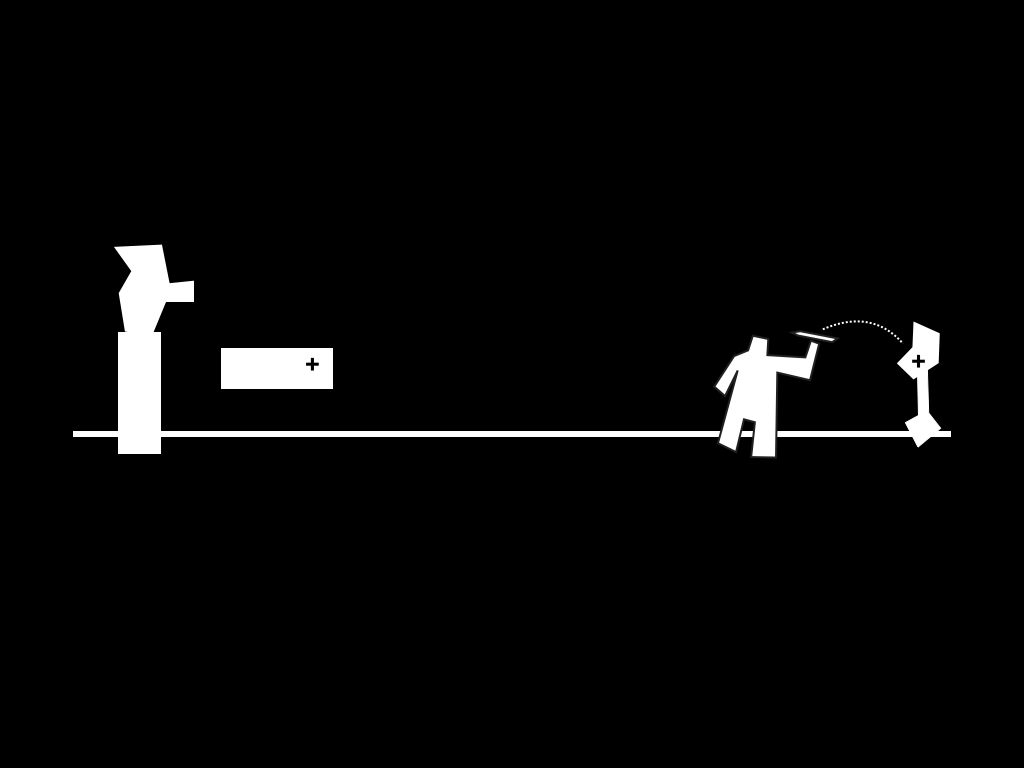

It also needs to happen in 30 seconds or less. That's the maximum amount of time that visitor services says it should take for a person to buy a ticket and get a Pen and start to poke around the museum. Anything longer and the lines at the ticket desk start to back up. Once the lines at the ticket desk start to back up then the Great Hall and the entrance to the museum starts to fill up. Remember, the museum is in an historic mansion which is bigger than my house or yours, probably, but is in nowhere nearly as large as the foyers in bigger museums like MoMA or the Tate.

Any delay in the process has an almost immediate ripple effect and it was very much a problem that the museum struggled with after the Pen was launched.

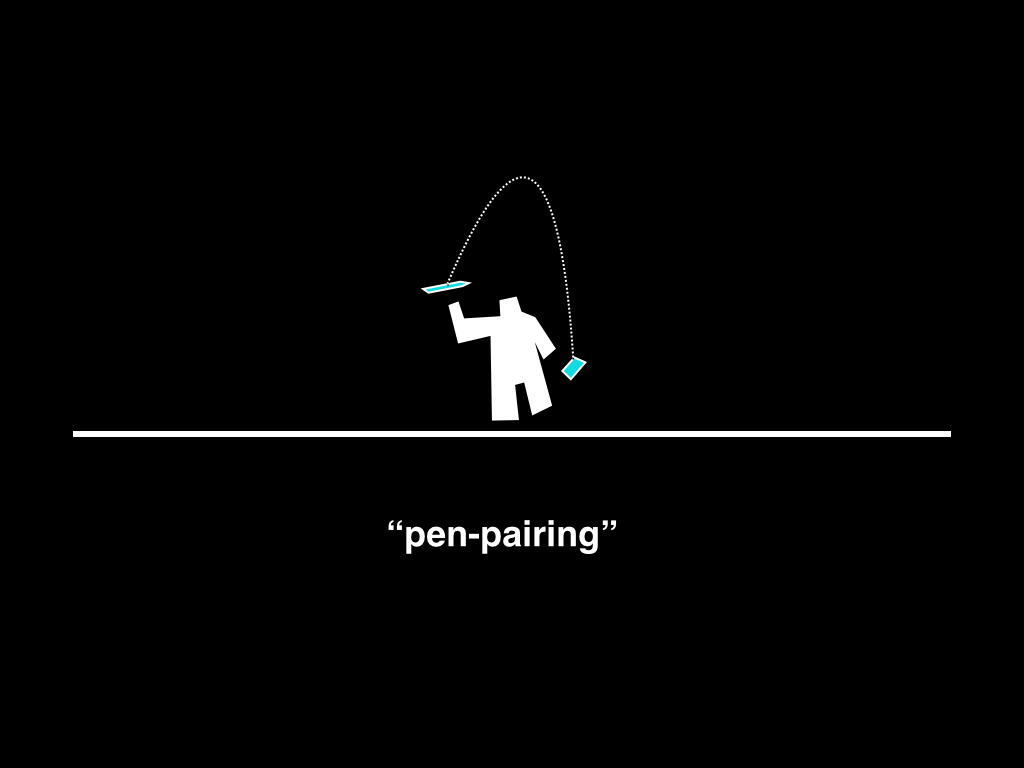

So at the end of all this you've got a visitor with a pen and a ticket which are paired

by way of a unique visit ID, printed on their ticket.

Visitors can walk through the museum collecting objects by pressing the crosshairs (or the collect

icon) on the back of their pens to the crosshairs printed on an object's wall label.

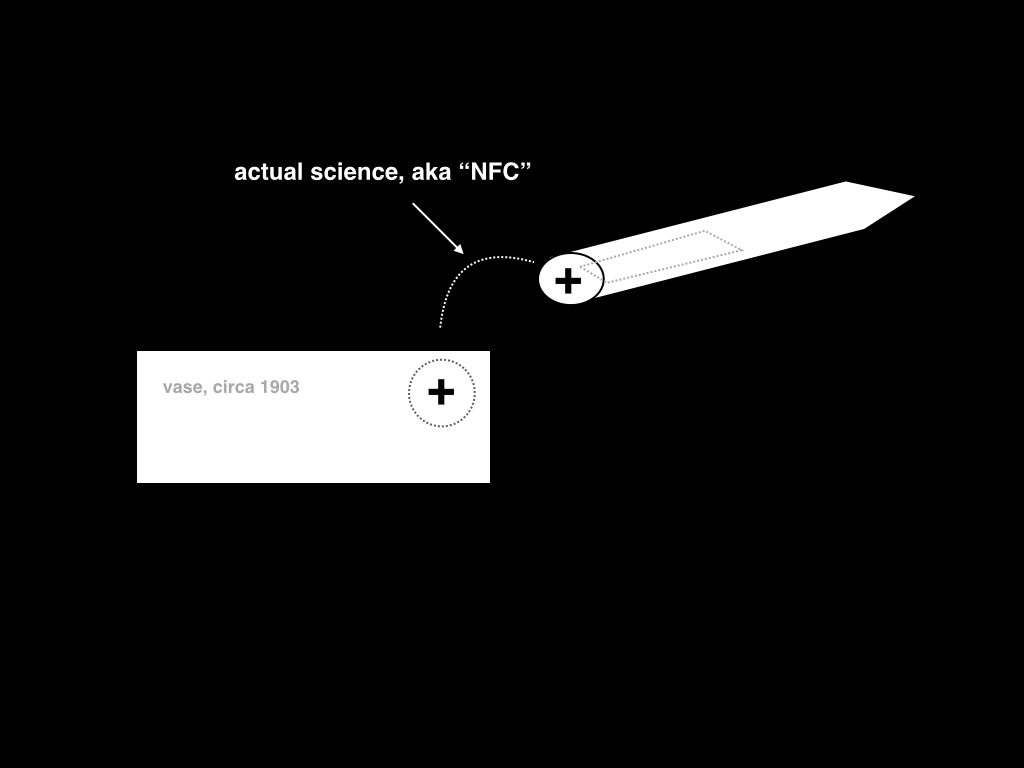

What's actually happening under the hood is something called Near Field Communications

or NFC. A passive NFC tag, on to which an object ID has been written, is embedded in the wall label and it is read by an active NFC antenna housed in the Pen.

The NFC antenna and flash drive are plain vanilla component parts so there's also a small micro-controller in the Pen that manages these interactions as well as the logic to get items off the Pen.

And when I say small I mean really really small. Designing and building the Pen was an exercise in pairing things down to the bare minimum out of necessity. In the museum's case necessity meant not having to charge or replace the batteries in the Pen more than once every three (or ideally four) weeks. Which really meant not having to charge the Pen at all since the Cooper Hewitt has a very small physical footprint, by museum standards, and there simply wasn't anywhere to plug in as many pens as we thought we'd need. In the end the Pen is powered by three triple-A batteries and doesn't even have an on-board clock since that represented a prohibitive power drain.

So at the end of all this you've got a visitor with a pen and a ticket which are paired

by way of a unique visit ID, printed on their ticket.

In addition to the NFC tags in the object labels there are also a series of large interactive tables and transfer

stations located throughout the museum, all of which also communicate with the Pen.

The interactive tables allow visitors to see what they've collected during their visit so far as well to see and collected other related objects that that have been loaded on to the tables. There are also a variety of creation

tools where visitors can make their own designs and save them to their visits.

The interactive tables both read data from pens and then sends it on to the museum's databases; the bits that actually store and display your visit. This is a required step because as I mentioned earlier the pens themselves don't have any smarts and definitely don't have any network magic. In addition to the tables there are what we refer to as transfer

stations. These haven't been widely deployed in the museum and it's not clear that they are either useful or necessary.

The thinking behind them was that if you needed to leave the museum in a hurry but didn't want to wait for a space at an interactive table or for the front of house staff to transfer your pen data after your departure you could simply tap your pen and have access to your visit items immediately. That was the idea, anyway, but in practice most people don't check their visits until they get home giving museum staff plenty of time to process pens after they are returned.

What both of these systems share in common, though, is that they are clients of the museum's API. The same API from way back in 2012. The Pen doesn't actually know anything about the API and similarly the API doesn't know anything about the Pen. The only thing either knows is, each in their own way, about lists of objects.

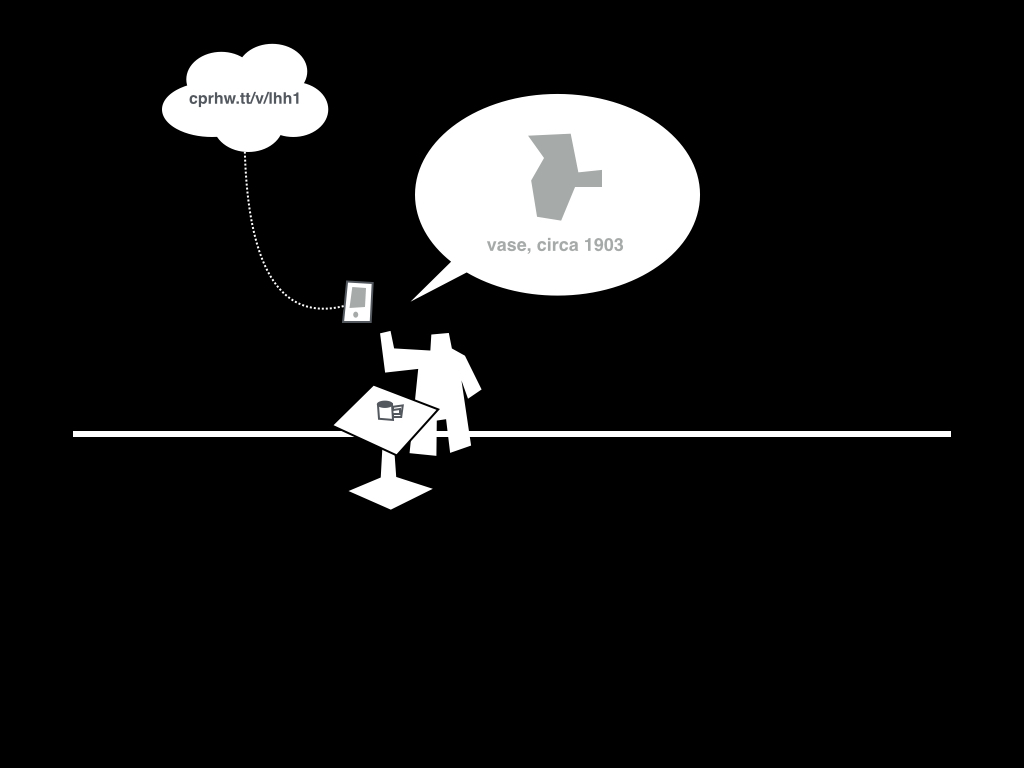

And what all of this means is that your visit lives on the web, ready for you re-visit at a time and place of your choosing. That might be during a coffee break at the museum, or later that night at home, or next week for a school project or a year from now when you're out with a friend and remember something germane to the conversation. Really, that's your business.

The point is that you can. That a museum is capable of making that sort of thing possible strikes me as both exciting and a responsibility. As museums all we do is keep things safe. We are never going to afford your visit the same time and attention that the collection itself gets but there's a lot of room between that level of care and doing nothing.

It's a little more complicated than this in practice but conceptually all the museum did was say We will give anything we consider to be a first-class actor in our universe — objects, people, exhibitions, visits, visit items and so on — a stable permanent URL on the web... and then make them all hold hands.

We will make the museum part of the web.

The NFC tags in the wall labels are also updated using a third API application called the label writer. This was really important because it means that the exhibitions team can have a dedicated application tailored to their workflow and, like the front of house (Pen registration) software, can be maintained and updated separate from all the other infrastructure.

So, the Pen has been on the floor for almost four months now. The numbers have been pretty rewarding for any museum, really, but especially a small museum like the Cooper Hewitt. There are two numbers I want to focus on. The first is that people have used the Pen to collect objects a million times, already.

The second is that people have collected over four thousand individual objects. There is no question that most of the objects collected are those on display and collected using the Pen but there is also a very real and very meaning long tail

of museum objects that are being seen and collected by way of the interactive tables. This is a big deal since there's really only room for about 700 objects on display in the the museum at any one time. This is a big deal since the Cooper Hewitt has over two hundred thousand objects in its collection, most of which will never leave the storage facility.

There was a time, though, when it wasn't clear that any of this would work as we'd imagined. For a lot of reasons — some good and some bad and some of which I've mentioned already — getting from the idea of a museum being a genuinely polite, robust and well-behaved part of the web to the reality was really really hard. This was entirely new territory for almost every part of the museum and required not just a leap of faith but also setting aside long-standing practices and in many cases biases.

That is hard. For any organization. It's hard precisely because no one person or group is at fault. It's hard because a leap of faith is exactly that. A standing leap rarely succeeds. It happens, from time to time but the rest of us still live in a world where leaping still requires some amount of momentum. Absent that, inertia takes over.

The trick became trying to find as many ways as we could to short circuit that intertia. The trick became trying to find a way to make the project not perfect but more real even if that progress was only measure in fractions. The trick became to force the debate and the decision-making process to deal in tangible material facts rather than aspirational doubt.

The museum had two things going for it, two things that allowed it to crawl out of its own anxiety. The first was friends who we could lean on for help and advice and general sanity-checking. Pro-top: Always have friends around. The second was the API.

The API

is sometimes spoken of as a single monolithic thing, something you can just buy off the shelf or license from a services company. It's not really. This is a diagram of the API

done by Katie Shelly. For most of this talk I've been talking about the blue bits at top of this pyramid.

The green bits represent all the work the museum has and had done prior to the Pen. Most importantly, it was work we had done in-house; it was work that we controlled. The green bits represent the work that we knew needed to be done in order for something like the Pen to work. Ultimately they represent the work that allowed us mock up and prototype something that looked enough like the Pen — evidence — that we could work up enough momentum to work up enough confidence to close our eyes and jump...

The reason I mentioned mine and Seb's departure at the very beginning was because a big part of the project, for me at least, was making sure we built something that could be handed off. The Pen, and everything about the re-opening, involved so many more people than just me or Seb. We both had senior roles and exerted a great deal of influence on the project and those are dynamics that, both internally and externally, lend people to believe (incorrectly) that a project lives and dies on the shoulders of one or two people.

No one is without ego and I am proud of the work

that I contributed to the re-opening but a project

that falls apart the minute any one individual walks

out the door is pretty much the definition

of shit work

.

So on top of everything else there was a larger meta-goal of using the re-opening itself to create a larger belief in and around the institution itself, beyond the reopening. Given the history and financial and staffing realities of contemporary museum practice I think we did pretty well. More specifically I think we succeeded in two areas and stumbled in a third.

- We have started to create belief inside the institution that the project is sustainable within the organization itself and not just one the shoulders of one or two people. It's early days and the real measure will not be in the first hand-off but in the third or the fourth.

- We have started to create belief inside the institution that not only is the project sustainable but that it can accomodate and adapt to the museum's ambitions. It is more than the very expensive one-offs that the sector has grown accustomed to.

- We did a pretty bad job of making our contractors believe in the scale and breadth and ambition of the project. We got there, in the end, but it was really hard. And I think as much, or even most, of the responsibility for that pain lies with the museum. Client-services companies can be forgiven for not believing a word their clients say. They'd go out of business if they weren't ruthless about the stuff they hear coming from the other side of the table.

The museum forced each of its contractors to forego the carefully controlled schedules and processes that they had developed and whether or not that was the museum's prerogative I think it is important to recognize that we could have done a better job of it.

Epilogue

In Novemeber of 2015 I attended the Museum Computer Network (MCN) conference in Minneapolis. On my return home I sent the following email to the folks at the Cooper Hewitt:

I was at MCN last week and more than a few people asked me what my (and Seb's) departure "meant" for the museum. Having I answered the question so many times I thought I would share with you what I said:

I am both pleased with and proud of the work that I did. I would like to think that I contributed something unique to the project but it was always the product of more than just me and Seb, even if we were often the loudest people in the room.

The timing of my departure was not ideal but I would never have left before I felt confident that the thing we built actually worked. Also if one the goals (and it was one of mine) was to build something robust enough to hand off to another person(s) then... well, you have to hand it off eventually.

But really the thing I am most pleased with is what's happened since my departure. Specifically two major and significant overhauls to both the front-of-house ticketing and the user-facing post-visit systems.

Given the scale and complexity and novelty of the Pen project it was inevitable that this work (or something like it) would have to be done. The Digital team have done it twice, in six months and all on staff time. That includes the conceptual work and all the research, the design work and the actual implementation.

At the time I forgot to mention that, in addition to the things listed above, the team also rebuilt the staff-facing admin tools for getting collection objects on to the digital tables, and turned around a major exhibition. There was also a third thing which I'm not sure is meant to be spoken of or even acknowledged but it's a big (and important) deal.

That is how it is *supposed* to be but the reality in the museum sector is that it has never been this way.

Normally it would cost at least another six figures in contractor fees with results that everyone will have had to wait another 6-18 months to decide are underwhelming all the while having to live with and suffer the original problem.

That the Cooper Hewitt was able to route around this dynamic, because it has the staff and the infrastructure and the institutional wherewithal, is awesome. That the Digital team was able to do all of that without either me or Seb around is even better.

Since leaving I have said to people that when it comes to "digital" the Cooper Hewitt can do more, better, faster - not to mention cheaper - than anyone else in the sector. Period. Those are meant to be fighting words because I would like to see someone take up the challenge. The sector would benefit from it. In the meantime the Cooper Hewitt should just be asking itself what it wants to do *next*.

Those goofy kids on the third floor are a good lot and with a little bit of guidance and little bit of indulgence they will take the museum further still.

So, you know, more like this...

This blog post is full of links.

#design-eagle