objects in the mirror are closer than they appear

This was a talk I delivered at the Technology experiments in art: Conserving software-based art symposium, at the Smithsonian's American Art Museum, in January. It's also a talk that Seb and I did together earlier that same week at the NY Cultural Tech Meetup and a re-telling and a continued poking-at of a talk on the same subject that we did for the Australian Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Material National Conference, in October 2013.

Also, the photo in the title slide is by a New York street artist named Jilly Ballistic who is awesome. There's a whole other talk to do about her work and the idea of artists spelunking through databases and archives and the part where I really only know her work by way of the Internet even though she shows

all her stuff in the subway. But this was not that talk.

Hi, my name is Aaron. I am the Head of Internet Typing at the Smithsonian Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum.

Most of the talks today have been about art and art museums. The Cooper-Hewitt is a design museum so the issues, the motivations and the approaches we bring to software preservation are often quite different than those confronting an art museum. We were invited to participate in this event for our acquisition of Planetary, an iPad application for visualizing your music collection, last year. The acquisition was made on the merits of its acheivement both as a work graphic or visual design as well as its interaction design. I will talk about those things more later in the talk but we also made this particular acquisition for a third reason which is what I want to start by talking about: That the issues and the opportunities raised by this particular acquisition can act as a lens and a testing ground for future acquisitions.

Increasingly the objects that all design museums collect will look more like like Planetary than not and they will face many of the same issues. Issues that no one is entirely sure how deal with. This may seem a little discouraging at first but that is cost of living in the present and we're certainly not going to figure anything out by standing around doing nothing.

I want to mention the Cooper-Hewitt itself, briefly. We are captial-D design museum, now housed in Andrew Carnegie's mansion in New York's Upper East Side. We did not begin life as a design museum, though, but rather as a decorative arts museum founded by Sarah and Eleanor Hewitt and conceived as a working collection

, a catalog motivated as much by its thoroughness and depth and open access to both amateurs and craftspeople alike as by its emphasis on quality and excellence. The Hewitt sisters' grandfather was Peter Cooper who had by then founded the Cooper Union which was created to, and until recently operated under the principle of, providing full-tuition scholarships regardless of background to all its qualifying students and to ensure them an education equal to the best technology schools established

. I choose to believe that both institutions have always shared common aspirations and I choose to believe that these sensibilities continue to serve us well as a design museum in 2014.

With that, I'd like to begin with a few quotes meant to act as a kind of soundtrack music for the rest of this talk.

This is a passage from China Mieville's last novel, Railsea.

This is a quote by Lady Gaga who has said she will spend two million dollars of her own money to create a museum for Michael Jackson's clothes, specifically the clothes he performed in. No, really.

This is a quote from Robert Litt, the NSA's lawyer, trying to explain why his boss, James Clapper the Director of National Intelligence, didn't actually lie to Congress when offering the least un-truthful answer

when asked about the collection of bulk telephony metadata.

I also considered adding a slide with Bill Clinton's famous quote questioning the meaning of the word is

when asked whether he had had an affair with Monica Lewinsky but the common thread in all these passages is the idea of motive and how we recognize it. That's an important question for all museums, but especially for a design museum since by-and-large we all have the same things in our collections. By their nature design objects

come in multiples, often to the point of being mass-produced or in some cases not even being considered design objects unless they are mass-produced.

For example, this is an AK-47 from the collection of the Kalashnikov Museum in Izhevsk. It is from the first pilot batch of assault rifles produced in 1948 that would go on to be adopted for use by the Soviet Army in 1949.

This is a Chinese-made AK-47 from the collection of the National Museum of American History. Which is to say: The Smithsonian has a Chinese-made Russian assault rifle in its collection. Is it just a talisman of the Cold War period or might we imagine that it was a gift from Mao Zedong to Richard Nixon during his famous 1972 visit to China? It is currently not on display.

This is an AK-47 from the collection of the CIA Museum. It was acquired

sometime in 2012. It is said to have belonged to Osama bin Laden. The museum remains closed to the public and I get the sense that it was never really meant to be known to anyone outside the family

in the first place.

By now you've probably figured out that these are all the same image and it's not any of the actual machine guns that I've been describing. By now you've probably all figured out that this is the same picture of the same AK-47 from Wikipedia, so here is a picture of a plush AK-47 by Mindy Sue Myers.

I might also have also told you that any one of those AK-47s belonged to a child soldier in Sierra Leone. That is was from a museum devoted to telling the history of child soldiers and the mineral wars that have plagued Africa for the last fifty year. So why does this matter?

It's difficult look at the CIA Museum's AK-47 and not also see Napoleon's Vendôme Column. For anyone not familiar with the Vendôme Column it's a big-ass sculpture in the center of Paris in a square originally built the celebrate the conquests of the French Empire. It was claimed to have made from the melted canons belonging to all the armies that Napoleon defeated at the Battle of Austerlitz. Napoleon was not lent to subtlety and the Vendôme Column is essentially the 19th century version of what many people today now associate with the fictional Conan the Barbarian's answer to the question What is best in life?

He replied: To crush your enemies. To see them driven before you. To hear the lamentation of their women.

If you think I am just being provocative stop for a moment and imagine what the reaction in the United States would have been if the Kalashnikov Museum had acquired Osama bin Laden's AK-47.

This on the other hand is a proper work of art by Peter Kennard and Cat Phillipps. It was on display at the Imperial War Museum in Manchester, in 2013, as part of an exhibition about contemportary art and war.

The late painter Francis Bacon gave an interview, somewhere around the mid-point of his career, in which he said that he aspired to create paintings that defied narrative. Whether or not he succeeded or whether or not he even still believed that idea by the time of his death is sort of irrelevant. We have always celebrated works of exceptional execution and in contemporary times we increasingly afford artists the luxury to pursue a singular itch to that end.

It is interesting to consider that as the art world and the discourse that surrounds it continues to get wordier and more theory-driven we are also seeing both museums and artists create works that can only be described as spectacles. That's a whole other talk but just keep this idea in the back of your mind: That people are starting to use spectacle itself as a kind of medium in part, I think, because it remains bigger than words.

I want to mention craft and the timeless arts-and-crafts debate only long enough to describe a scenario guaranteed to upset everyone involved. That capital-A art is the Abel to capital-C craft's Cain, but with a twist. If art will knowingly murder his brother the problem he faces is that his brother is also a zombie who can never die and wants to eat his brain.

It's not a very flattering picture for anyone but the reason I enjoy this fiction is because it's a useful way to consider design. That is, design is the shadow of the unresolvable struggle between an outstanding, over-achieving sociopath and a his seen-to-be lesser too who refuses to give up no matter what anyone says.

This is the world's first operational 3D printed hand gun. It was acquired by the Victoria and Albert Museum last year. It is worth mentioning that in writing about the acquisition Dezeen (.com) made a point of noting that the original prototypes did not arrive at the museum in time for London Design Festival, so the museum printed out a copy in London based on (the) blueprints.

Right?

Because, you know... it's a 3D printed object. The whole point of 3D printing is to make anything Walter Benjamin ever said seem quaint by comparison. That does not make it any less difficult to resist the allure of a thing imbued with aura, whether it's real or imagined. Is the very first 3D printed hand gun any more or less special than the very first AK-47?

I mentioned that the Cooper-Hewitt began life as a decorative arts museum. One way to consider the decorative arts is that they are exceptional forms of traditional craft. But more importantly, that excellence is also reliability reproduceable. Without that guarantee there is often only the argument about whether something is art or craft.

There's a reason that many design museums began life as decorative arts museums. Long before capital-D design existed the decorative arts existed to provide beautiful yet functional objects to those with the means to pay for them. In the last hundred or so years we've seen the decorative arts transforming in to something that we now better understand as design

. As the fruit of those labours began to reach, and were ultimately influenced by, a larger body politic you begin to see the practice of creating elegant and serviceable products being applied to more than just decorative objects.

So we might consider contemporary design practice as akin to the decorative arts but with motive or deliberation. It is not the singular exceptional itch of the indivudual artist but rather the art and craft (sorry) of an elegant solution to a problem that can be articulated, in the service of a plurality.

Here’s the rub, though. No matter how impressive or elegant a solution they are not meant to be contemplative endeavours. They can't be. Imagine any thing you consider to be an elegant design solution or object and then try to imagine having a PHILOSOPHICAL MOMENT every time you used it.

We celebrate design that ultimately can be taken for granted. We celebrate a practice whose products afford us the plausible illusion of fading in to the background, of not always demanding center stage, and of not asking us to spend our already too-busy lives in a state of near-constant intellectual Rapture.

Which is hard for museums because we are all about the Rapture.

Remember, that is the luxury that we have always afforded high art. It's okay. The problem for a design museum is that we are all collecting the same mass-produced objects whose surface elegance is often doing battle to actively hide from its users the complexities of its motive or production. We are left to unpack things that exist to dissolve in to the normalcy of our lives.

We’re still not very good at that. We have a bad habit of falling back on how pretty

a thing is or the mastery of its manufacturing prowess or a designer's access to production facilities as proxies for the merit and value of a design solution. The problem that design museums are facing, though, is that we’re increasingly collecting things which have no thing-ness about them so the rhetoric we've always used to talk about our collections make less and less sense.

Things like interaction design or service design or user-centered design or experience design. Given the challenge we already face collecting physical objects what are we supposed to do with practices that are as real as they are intangible?

Do you know who spends a lot of time trafficking in experience design, possibly more than anyone else in the aggregate? Museums.

What else are dioramas except early stage attempts at experience design? Because dioramas are basically fancy display cases for delicate or senstive objects we don't usually allow people to wander around in them. But when you consider that the film maker Peter Jackson, and his production company Weta, are creating a life-size trench experience

from the Gallipoli Campaign inside Te Papa, the national museum of New Zealand, it doesn't seem like it will be long before museums can finally indulge their almost Captain Ahab like fantasy of a truly immersive experience. Personally I am waiting to see whether the trench installation offers a night at the museum

style package where you can sleep in a pool of standing water, swatting away rats all while dodging ear-shattering explosions. When you stop to consider the many inevitable retrospectives that New Zealand museums will mount to celebrate the career of Peter Jackson, a native son, the crossover possibilities are endless.

For the time being we're left with stuff like this. This is a diorama from the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Punk: Chaos to Couture exhibition last year. It is a recreation of the men's bathroom at the now defunct music venue CBGB's where many of the bands that would shape the musical genre got their start. If you're wondering: It's not a functioning bathroom or, if it is, there's no way to find out because there's a short glass barrier preventing you from entering the space.

The exhibition's curators made a point of saying that the exhibition was about the influence of punk rock on the world of fashion and that they very deliberately stayed away from the politics of those involved. Which if we take them at their words makes the inclusion of an installation like this all the more problematic because it's the kind of thing where malice is almost more comforting than simple negligence.

I am going to leave the interpretation and meaning of using a tarted-up version of a gritty

bathroom as a proxy object for... something as an excercise for the audience and only say that this installation was very deliberate and entirely with motive. It was designed.

Fiona Romeo’s essay Can An Exhibition Be A Story? is an excellent discussion of some of these larger questions surrounding exhibition design and I'd encourage you to read what she has to say.

I’ve been joking for about a year now that the Cooper-Hewitt has acquired the Global War on Terror as an outstanding example of contemporary service design. This is a deliberate provocation meant as a way to force people to consider something which undoubtedly will be collected eventually but for which we lack any good conceptual guidelines to suggest how or what to collect. Do institutions collect the security theater that has plagued American airports for over a decade now? Do they collect the empty rooms with the angry dogs in them? Do we simply preserve those rooms or do we operate them as an interactive element of the museum that visitors can experience?

And then this happened.

This is a photograph of a group called Witness Torture protesting the continued operation of the US detention facilities at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. This photo was taken yesterday at the National Museum of American History in front of, as you can see, an exhibition called The Price of Freedom: Americans at War. You might not know that, though, unless I'd told you. You might reasonably enough look at this photo and think these were mannequins and that they were a bold and challenging position taken by the curators and exhibition designers on the cost of war in the 21st century.

Tangentially related, at this point during the talk the mystery guy who'd been sitting by himself at the back of the room all day suddenly got up and left...

Or how about this? This is an actual water-boarding device from an actual museum. This is on display at The Tuol Sleng Museum of Genocide in Phnom Penh. The genocide refers to the Khmer Rouge regime and the museum itself is housed in the former Security Prison 21, itself a former high school, where up to twenty thousand people were tortured and killed. You're not supposed to talk about water-boarding as experience design

in polite company but it is about as designed an experience as you can get.

Meanwhile, about a week ago I started hearing the phrase hardware is the new software

a lot. I think this is partly because we've just come out of the hype cycle around CES, the big annual consumer electronics exhibition in Las Vegas and partly because of all the excitement around 3D printing and DIY-hardware and, of course, partly because if you're Nest you just made 3 billion dollars selling your hardware company to Google.

I don't think that hardware is the new software, though. I think one thing that might be happening is that we are starting to see the end days of a twenty or thirty year stretch of relatively agnostic hardware and that will usher in a whole new set of changes. As the hardware that is produced becomes more and more like gated communities we are starting to see some of the same dynamics around access to the means of production and distribution that existed (that still exists in many cases) in traditional product design before the advent of fast and cheap manufacturing.

But make no mistake, whether you or I continue to have access to that hardware it's all still full of software.

The agency of all that hardware still lives in the software.

Consider these trash bins in London. It was discovered in the summer of 2013 that many of these bins had been fitted with wireless tracking devices, from a company called Presence Orb, that would record and log the unique addresses of the wifi chips in passing cellphones. The idea of the company behind the scheme was to sell the information it collected and analyzed to advertisers although the program was quickly shut down when the general public became aware of it.

This is a photo by James Bridle who walked around London drawing a variety of icons in chalk on these trash bins to try and make visible the presence of intent in these objects.

Here's a slightly less creepy version of the same sort of thing that we've lived with for years now. Does anyone really feel like they understand how their smoke detector works or how it chooses when it will lose its tiny robot mind and start screaming at them? We know how a smoke detector is supposed to work but almost everyone will tell you their smoke detector might as well have a mind, and a motive, of its own for all that anyone understands its behaviour. Here's the marketing copy for Nest's take on the smoke detector, simply called Protect

:

Before turning on a loud, howling alarm, Nest Protect gives you an early warning we call Heads-Up. Nest Protect lights up yellow and speaks with a human voice. It tells you where smoke is or when carbon monoxide levels are rising. This gives you an earlier warning if there’s an emergency, or allows you to silence Nest Protect if it’s just a nuisance alarm, like an overly enthusiastic toaster.

I have not taken one of Nest's smoke detectors apart to investigate what's going on inside and maybe there are some sophisticated sensors in there but it's basically just a smoke detector like all other smoke detectors ever made. It's nice that it can tell you some of the details of what it thinks is going on but the important part is that it chooses to tell you anything at all before freaking out.

We don't have sensors for choosing

yet. We still have software for that.

That distinction between sensors and decisions is important to keep in mind. Once upon a time there was a website where you could share your travel itinerary with friends and relations. It was called Dopplr and has since gone out of business but during its brief life it would calculate your carbon tprint based on your travel plans. I remember hearing one of the founders, Matt Jones, describing their motivation for adding this functionality as wanting to be the scale, not the diet

. Dopplr did not want to be in the business of telling you what to do, it wanted instead simply to show you what you were doing.

Museums, I think, liken themselves to the diet and so we've spent quite a lot of time collecting scales. This is a practice that is becoming increasingly problematic not because there's anything inherently wrong with it but because the world around that practice is changing.

This is another product from Nest, it's a networked thermostat that adapts itself and its settings as it monitors how and when you heat your home. It's pretty clever. We have a pair of them in our collection. They are elegant pieces of industrial design. We did not, however, acquire any of the software that powers them.

So you might be forgiven for asking if we haven't just acquired this year's knock-off of Henry Dreyfuss' classic T86 Round thermostat. Remember, the Cooper-Hewitt was founded as a working collection so there is a solid argument to be made for collecting the Nest thermostat on precisely those grounds.

But to consider the Nest thermostat solely as a work of industrial design — of manufacturing prowess — seems like a missed opportunity at best and completely missing the point at worst. To make matters worse we don't know how to collect all that other mysterious stuff that makes the Nest thermostat remarkable. We have neither the conceptual nor the technical infrastructure to house and preserve the software systems that power the Nest nor do we have the legal infrastructure to make a still-active company in the marketplace comfortable giving us that source code with the trust and confidence that we won't share it with the rest of the world.

This is really important. It would be unfair and unrealistic of us to ask Nest for their source code at this point. That software rather than the fancy plastic molds which house that software (and that will change next season anyway to accomodate the demands of fashion) is Nest's business and so it suggests the need for cultural heritage institutions to begin imagining something akin to an escrow system for intellectual property. Because without that all we will be left with in a hundred years is some off-gassing plastic shells and the breathless rhetoric of printed marketing materials to help us understand the past.

For example we have one of the millions and millions of iPhones that have been sold since 2007. We even have a first generation iPhone but to the best of my knowledge there is no hero-story behind it. It was not acquired, or donated, by anyone who stood for hours in line at Apple's flagship store in San Francisco on the day it was first released. It was purchased, most likely and like so many other iPhones, online and delivered a few weeks later via UPS. It is just like the iPhone you probably have sitting at the bottom of a box and which you are keeping for sentimental reasons and because it represents a moment when the promise of the future seemed like it had been realized, however briefly.

These are pretty good reasons for collecting a thing and it's why we'll do more than you will to make sure that our iPhone suffers fewer of the ravages of time. That is why institutions like the Smithsonian exist. And even more than the Nest thermostat the iPhone is a King Hell example of manufacturing and production. Like the Nest, though, we did not acquire the software that runs the iPhone. Given the state of acrimony and competition in the mobile industry it is unlikely that Apple will ever let that source code see the daylight outside of their soon-to-be giant donut-shaped fortress in California.

Again, it suggests that if there was an institution of trust on the scale of the Smithsonian or the Library of Congress, an institution with both legal and moral backing then maybe we could imagine a scenario where those materials would be placed in a trust that would safe-guard them from ever being seen in our lifetime but would also prevent them from being lost to future generations. This is not as far-fetched as it sounds. This is basically what museums look like in a world where the Internet exists. Who among you has seen all the objects in the Smithsonian's collection? Who among you has ever seen, or even knows about, all 213 thousand objects in the Cooper-Hewitt's collection? In a world where people take networked databases for granted museums increasingly start to look more and more like the world's biggest conceptual art project; preservation without access starts to look more and more like blind faith.

Even if we take a punt on the very real challenges of trying to create a preservation framework for still-living intellectual property, the more immediate problem we face is one where museums often won't even turn on the electronic equipment in their collections. That iPhone we've got with its version of iOS 1.0 (or maybe it was upgraded before we acquired it?) will remain forever powered-off because we risk damaging the circuit boards or simply because we've removed the battery to prevent the risk of it leaking and damaging the other objects in our collection. It all seems like a theater of the absurb, sometimes. The worst part is that in the absence of working solutions for genuinely hard problems we do these things for good reasons. But can we meaningfully talk about the iPhone without talking about the touchable interfaces, about the interaction design that was afforded by all that swiping? In short, about the software.

Aside from all its qualities as a stand-alone design object this is why we acquired Planetary. Planetary does not answer all of these questions but it does force us to address them.

Planetary was the first product by Bloom, a San Francisco startup founded in 2010 by Ben Cerveny, Tom Carden, and Jesper Andersen, to explore new forms of data visualization and interactive products. It visualizes a user's music library as a series of celestial bodies. Songs are moons, albums are planets, artists are suns—and the orbits of each are determined by the length of albums and tracks. Their brightness represents their frequency of playback; songs and artists played less frequently than others drift further and further away, over time, from the planets or suns they orbit. Planetary is also a working music player and the time it takes for a moon to orbit a planet is governed by the length of the track that moon represents.

Bloom was fond of telling people that it was creating a suite of "pop culture instruments" and that Planetary was just the first of many. At the time the company was launched Ben Cerveny, one of the founders, wrote:

We’re building a series of bite-sized applications (instruments) that bring the richness of game interactions and the design values of motion graphics to the depth and breadth of social network activity, locative tools, and streaming media services. . . . These Bloom Instruments aren’t merely games or graphics. They're new ways of seeing what's important.

What I like about the idea of these small bite-sized tools to visualize discrete problems, or sets of information, is that you see this idea popping up all over the place these days. Just think about the number of charts and graphs and other visualizations that are available to you every time you view your bank account online.

Consider the amount of effort that goes in to trying to help you make sense of just your spending habits and then multiply that by the volume of information we are creating and leaving behind us like a shadow of the past keen to fill the vacuum of the present. Consider the work of Nicolas Felton whose obsessive and beautiful annual reports detailing the various facets of his life everyone gushes over and which Facebook eventually operationalized in their Timeline feature. Consider the NSA.

They do this too and they do it really well, arguably better than anyone else right now. If you see past the graphic horror of their PowerPoint slides and look carefully at the scale of their endeavour and the ways that they claim to tackle the challenge and you start to see tools like Planetary.

Honestly it's hard to get passed the names for the Planetary-like tools and projects that the NSA builds for itself. On top of everything else our burden will be to live through the next fifty years worth of critical etymologies and hand-wringing surrounding the hidden meaning of names like DROPOUTJEEP and SOUFFLETROUGH.

But every time someone talks to you about personal informatics

understand that the NSA is trying to solve the same basic set of problems and replace the number of miles you ran or the colour of your baby's poo with the question of Original Sin. In seeing the meaning of past actions as a way to make sense of present intent. Of judgement.

Since this is a symposium on software preservation I am going to suggest that if there is any one industry the cultural heritage sector should look to for tips and tricks on how to navigate a world gone increasingly digital it is the surveillance industry. It is, perhaps, not an association we would like to make but when you remove the agonies of interpretation our respective practices share more in common than not. It is worth remembering the Smithsonian's own Reginald Creighton, who was the manager of Information Storage and Retrieval Projects and would help shape the Selgem collection management system, did so after having spent over a decade doing systems programming and methods analysis... at the National Security Agency.

Because, here's the thing: Planetary doesn’t work anymore.

Or rather, it no longer works on the latest versions of the iPad's operating system. It stopped working about six months after we acquired it, with the release of iOS 7. Remember that three million people installed this application on their iPads. For many of them Planetary simply vanished one day. We knew, or were reasonably confident, that this would happen when we chose to acquire Planetary.

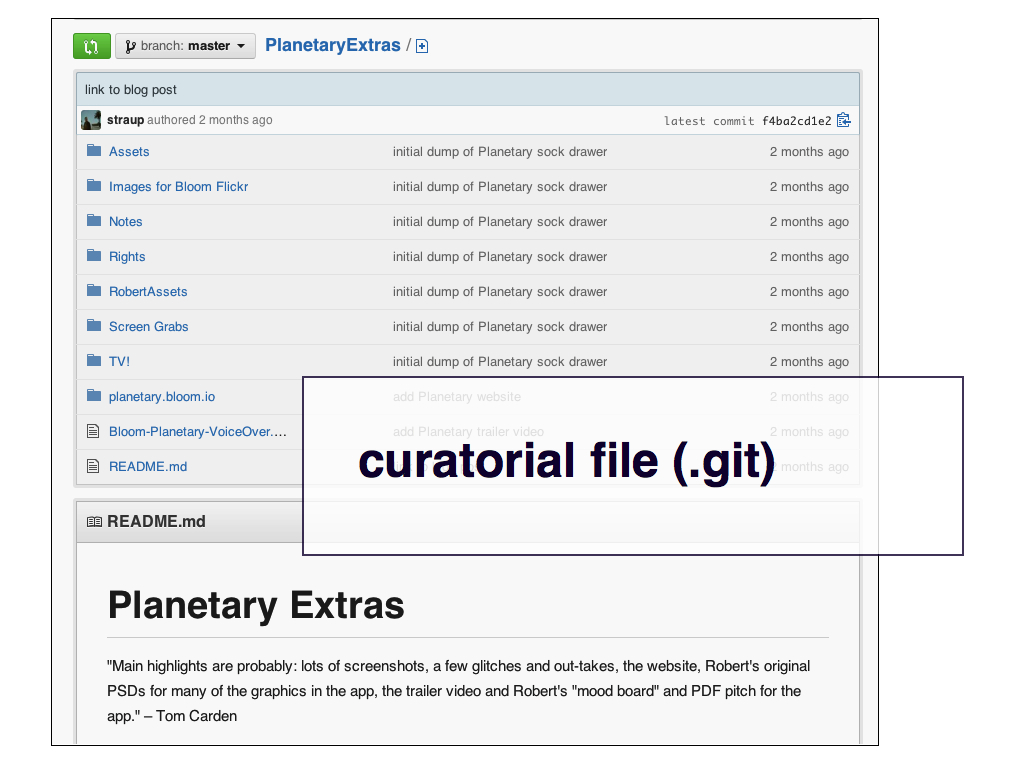

So the first thing we did was to open source all of the software, under a BSD license, and as many of the visual assets as were ours to do so with. We open sourced the code as a preservation strategy. We open sourced the code because we want people to port it to other systems. We want Planetary to live on beyond any one device or operating system.

We open sourced the code but we also released the complete revision history of that code, including all the bug reports, so that people could see both how and why the decisions were made and to understand the trade-offs that created Planetary. As a design museum those trade-offs are paramount to the things we collect. For all the stories of Steve Jobs' perfectionism the history and success of Apple is based on what they've been able to accomplish in the moment and not the magic happy pony world any of its employees wishes were possible.

We also released as many of the draft sketches and notes as we could get our hands on. In a way we open sourced the curatorial file that all museums keep for their objects. I hope we, and other museums, do more of this. This is where the velocity of an object’s history within an institution is encoded and that institution or curator specific understanding of an object, cut across time, is what distinguishes one museum from another.

We are trying to imagine how we might collect an object that looks something like this. When we announced the acquisition Seb wrote:

We liken this situation to that of a specimen in a zoo. In fact, given that the Smithsonian also runs the National Zoo, consider Planetary as akin to a panda. Planetary and other software like it are living objects. Their acquisition by the museum, does not and should not seal them in carbonite like Han Solo. Instead, their acquisition simply transfers them to a new home environment where they can be cared for out of the wild, and where their continued genetic preservation requires an active breeding program and community engagement and interest. Open sourcing the code is akin to a panda breeding program. If there is enough interest then we believe that Planetary's DNA will live on in other skin on other platforms. Of course we will preserve the original, but it will be 'experienced' through its offspring.

We are fortunate that Bloom's CTO Tom Carden has agreed to make himself available, for a couple of years at least, and if anyone ever does port Planetary to another system — maybe as an Android application, or a WebGL application so that Planetary will work in a web browser — he will look over those changes and be the final arbiter of whether or not those changes reflect the intent that Bloom was working towards. This kind of collaboration is really important both for Planetary and, I think, for other software preservation projects. We are not interested in preserving particular bits of Objective C source code but rather the thing which that code birthed.

Don’t worry, though, we also printed everything out on archival paper using the approved OCR-compliant typographic conventions. Maybe one day someone will recite the source code for Planetary the way people perform Homer's Iliad or Joyce's Ullyses?

But, I want to emphasize that we did not acquire an iPad. We already had one of those.

We acquired source code that happens to have been written for an iOS device. This fact tells us something about the circumstances under which Planetary was created but I don't think that it defines what Planetary is or was trying to be. The iPad was simply the then-best representation of what Planetary was trying to be.

Had Bloom survived longer as a company they would have almost certainly released an Android version of Planetary and then what? Which one would we have acquired? Both of them? Only the iOS version because it is not so much the genesis of the project but the first manifestation of it? What if the Android version, by virtue of whatever hardware or operating system level optimizations it enjoyed, better embodied the spirit of the project?

So yeah, we acquired code because to my never-ending dismay it's just Sol Lewitt all the way down but we acquired that code as a way create an environment that will hopefully foster the preservation of the interaction design that was at the root of Planetary. Have we succeed yet? Probably not. Have we created the circumstances that will afford that preservation? I hope so.

Since the acquisition, this a thing that's also happened. TinySpeck, a small software company based in Vancouver and San Francisco, released all the artwork and eventually most of the software for their failed mutli-player online game called Glitch, in to the public domain. Writing about the decision to place all the Glitch artwork in the public domain CEO and co-founder Stewart Butterfield said:

[B]ecause when you come down to it, as a species, culture is all we’ve got. The more of it we make, the better. The freer the materials the easier it is for people to make new things. Glitch was not a significant cultural milestone in its own right, but we hope that it has an outsize impact in its ability to foster the creation of more art and the expression of more creativity.

One of the things that made Glitch interesting is that at its core the game was a really just series of triggers. The game itself did not have any single narrative arc. Instead every object was programmed to operate inside of certain constraints and then the world of the game was left to form itself based on how the players interacted with each other and their environment. So I like to understand what TinySpeck did in giving away all their stuff

as another example of using open source as a preservation strategy for an endeavour that is very real but which lacks, by design, the known and quatifiable territory of a single work of art

.

To give you some idea of what I mean when I say all their stuff

this is an exploded view of the pieces that made up any given scene in Glitch. Every one of those trees or flowers or background elements, along with the metadata indicating where to place those objects in a given scene, were made freely available for anyone to play with or to use as the building blocks for future projects.

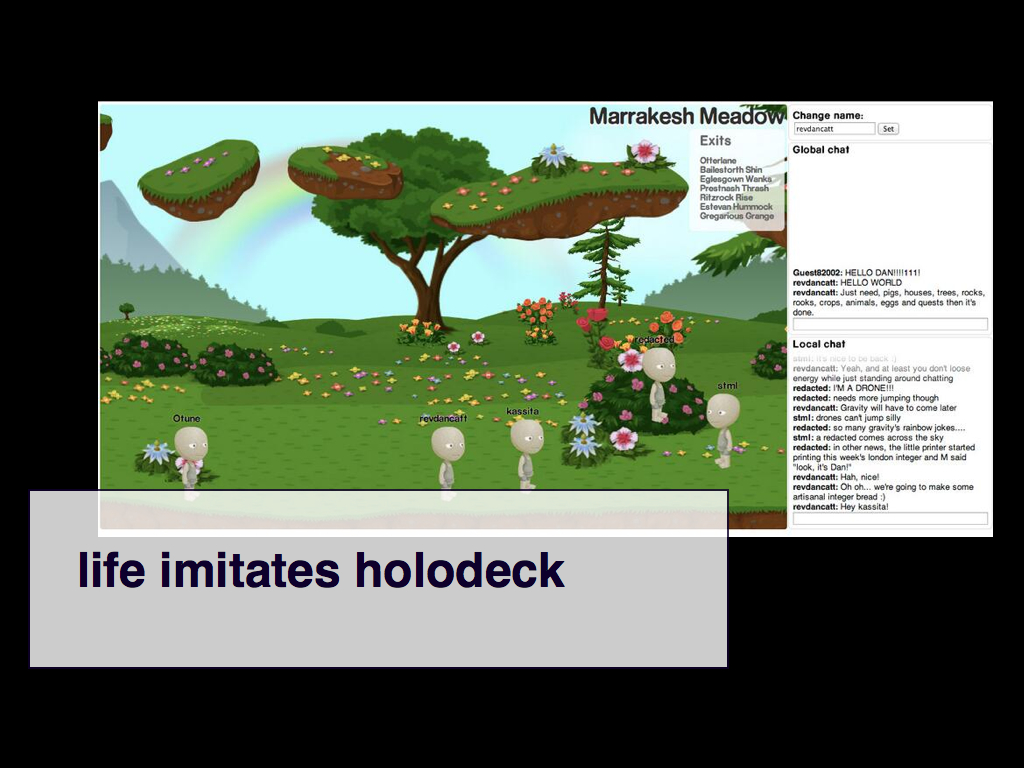

That screen shot is from a blog post by Dan Catt. Dan's project, and there are other more ambitious projects like his, is to try to rebuild a kind of minimal viable version of not so much the game itself but the parts of the game that he used; the parts that he now misses.

This is what the project looks like today. You could say that it's little more than a glorified chat-room but I think that does a disservice both to the intensely social nature of games like Glitch and the role that that the graphic design and constraints of the interaction design played in foster that social environment. Also, it works. It is the proverbial diorama that allows entry to visitors.

I think this is important work to watch. I don't think it will solve all of our problems but I think that it suggests what the path we will follow in the years to come will look and feel like. I think that as we are forced to find ways to collect and preserve things that are simply too big and too complex for any one institution to grapple with we might instead focus on the many smaller variations-on-a-theme that spring up in the wake of an endeavour as a way to hold on to the original.

Dan's project is not necessarily Glitch as its creators imagined but is it Glitch enough that perhaps we might look to the theater, with its multiple and on-going performaces of a single text, as our inspriration? Perhaps it allows us to imagine software preservation the way one imagines a working collection.

This blog post is full of links.

#objects