Stories from the New Aesthetic

So, last night James Bridle and Joanne McNeil and I got together again and did a(nother) panel about the New Aesthetic at the New Museum, as part of Rhizome's New Silent lecture series. I think the event was sold out or nearly so and that was really lovely. Thanks, everyone who came! Given all that's been written and said since the first panel in Austin this spring it would be a lie to say that there wasn't some trepidation about what a second panel and audience might end up looking like. In the end it was all good, I think, and we each managed to just focus on the things we've been thinking about since March. We told stories.

Joanne has posted her notes as has James. Also, Paul Soulellis published his raw notes about the panel. This is what I said.

I've been thinking a lot about motive and intent for the last few years. How we recognize motive and, more specifically, how we measure its consequence.

This is hardly uncharted territory. You can argue easily enough that it remains the core issue that all religion, philosophy and politics struggle with. Motive or trust within a community of individuals.

The security expert Bruce Schneier recently published a book about trust titled Liars and Outliers in which he writes:

In today's complex society, we often trust systems more than people. It's not so much that I trusted the plumber at my door as that I trusted the systems that produced him and protect me.

I often find myself thinking about motive and consequence in the form of a very specific question: Who is allowed to speak on behalf of an organization?

To whom do we give not simply the latitude of interpretation, but the luxury of association, with the thing they are talking about?

I have some fairly selfish reasons for thinking about this after having spent a number of years inside a big company and arguing about the value, or more often the relative risks, of releasing experimental or nascent features that may not square with an organization's singular narrative.

But the consequences of someone in government, for example, speaking in a way that exposes them or their department to a lawsuit is very real, whether or not it's actually warranted. We have instrumented a legal system in this country that allows people to enforce penalties on other people's actions not unlike the way patent trolls file pointless suits because there's real money to be made doing it. Motive works both ways.

Some of the resistance is also an historical function of the cost of production - in both time and money - and immutability of how we've built things in the past. Institutionalizing or formalizing consequence is often a way to guarantee an investment but that often plows head-first in to the subtleties of real-life.

Consider Jonathan Wallace's An Auschwitz Alphabet which is a website described as twenty-six slices ... to illustrate the entire human landscape of the concentration camp.

I first heard about this during the debates in the 1990s about whether or not website creators should be rating their own work. At the time, Wallace wrote:

Assigning an R rating to the file on human experimentation ... would place it in exactly the same R-rated category as sexual material with no SLAP value whatever, and would prevent minors with a perfectly legitimate interest from seeing it. Under a rating system which paralleled what we do for movies, I would either have to assign An Auschwitz Alphabet a G rating or refuse to rate it entirely.

I have memories but can find no actual evidence that Yahoo! banned the Auschwitz Alphabet, from its directory listings, on the grounds that it was inappropriate content and not suitable for a family brand. So, consider that possibility as a kind of more-than-likely design fiction.

I am newly arrived at the Cooper-Hewitt, here in New York. My job is to help figure out what it means, and how, to make the museum native to the internet.

If the pressure on museums was once only to remain internally consistent we are now confronted with the prospect of trying to enforce brand guidelines across the entire network.

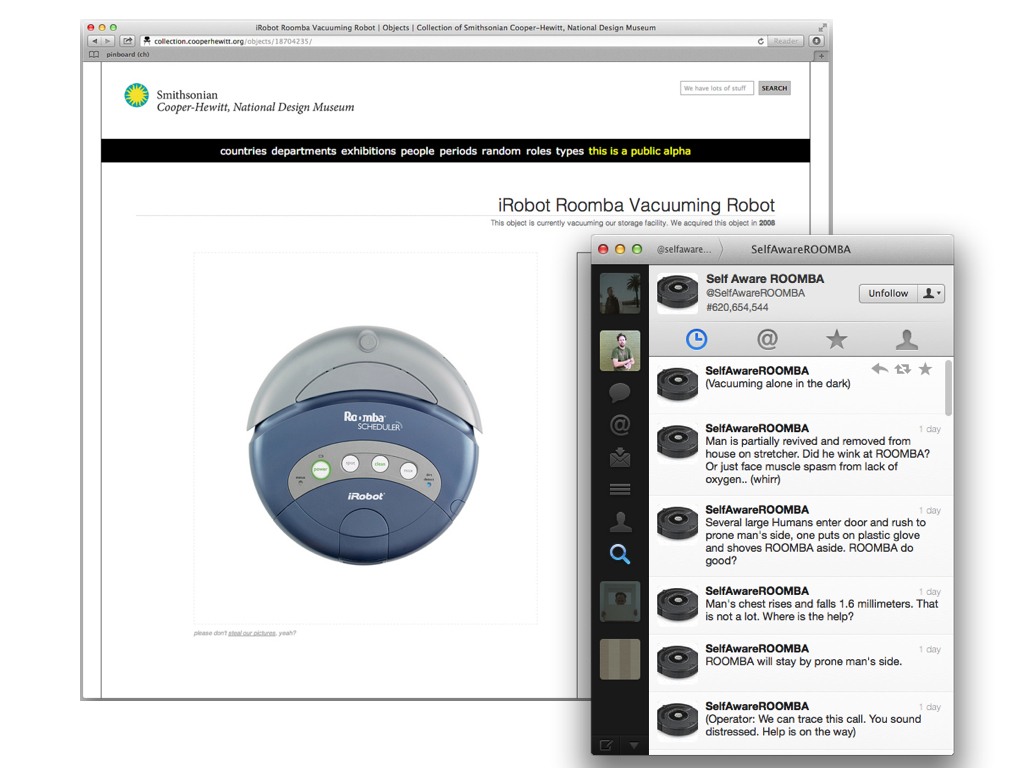

Because this is what 2012 looks like for museums.

It is most definitely not about Twitter but about the fact that some random person out there on the Internet is building a record of understanding about Roombas that may well rival anything we will ever do ourselves.

Beyond that, we are being forced to accept the fact that our collections are becoming "alive". Or at least they are assuming the plausible illusion of being alive.

We are having to deal with the fact that someone else might be breathing life in to our collections for us or, frankly, despite us. We are having to deal with the fact that it might not even be a person doing it.

That there's a person out there pretending to be a Roomba just means that we are beginning to believe that a Roomba might actually do this itself one day.

And never mind the robots that we can see. We are instrumenting everything around us with sensors. We don't typically think of the whale songs that elevators make every day as story-telling but it's not a stretch. Certainly not if we're even going to talk about whale songs for which we have absolutely assigned motive in the absence of any understanding.

Either way, it's happening out there on the network.

Personally, I'm okay with all of this.

I have always argued that as museums our goal should always be to get people inside the building, to see the actual things we collect. There is value in rubbing up against them in the flesh.

At the same time, a museum's digital presence is the first, and sometimes only, avenue that people have to get to know a collection – be they scholars, casual visitors or increasingly the network itself.

This is especially true for the holdings that, for one reason or another, never actually see the light of an exhibition room and we need to get comfortable with the idea that a single narrative motive is often doing our collections more harm than good.

Even if we're not entirely sure how to measure the ways in which those stories might blow back or get confused with our own.

If museums are going to spend all their time worrying about whether or not we are being "brandjacked" then we also have to be able to answer the uncomfortable question of: What is it that makes us different from any other shareholder-driven business hawking a stable of character franchises? —I left this part out of the talk proper, in the end, but it's still true.

I had the opportunity to visit Dia:Beacon last month and some of my favourite pieces were Gerhard Richter's plate-glass Rothko paintings

.

They reminded me of Lisbon or rather of a Lisbon that I only just caught a glimpse of, once.

If you've never been to Lisbon the city is defined by its hills and by the omnipresence of heavy wooden doors and shutters painted forest green. And yet behind so many of those wooden doors you'll find the same floor to ceiling plate-glass doors you find in every other city in the world.

We were walking past the train station one day where two businesses facing each other on opposite sides of the street had each opened their heavy wooden doors. Their interior glass doors were left to start parroting the city and sky and everything that they could also see including the doors across the street. It was beautiful and disorienting and it felt, just for a moment, like an entirely new Lisbon.

The chances of convincing the Portuguese to throw off a thousand years of history and big green doors, in the service of a million new hypothetical vantage points, are probably zero but I was reminded of that moment looking at Richter's work.

The idea of the city exploding in to a feedback loop with itself – of bursting through, as James likes to say – feels like a useful way to think about how we're teaching digital things to dance in the world and what we see in the the funny ways they react to it.

We're really good at pattern matching. By which I mean we're really good at seeing patterns and of making them out of whole cloth.

And we are starting to ask the network – the machines and cameras and sensors and cables and all the pipes, visible and invisible, that connect them and surround us – to look for patterns too. We're trying to teach pattern matching and we're not sure what to do with what's coming back

I am not here to argue that the robots are really seeing anything yet - at least not on our terms.

What interests me is that we - not the robots - are the ones seeing the patterns coming back and we know from experience the kind of crazy-talk narratives that could be shaped out of them. We can see both motive and consequence birthed in those patterns.

There is a larger question of whether our willingness to allow the robots to act *of their own accord* on those constitutes de-facto seeing but, by and large, we continue to actively side-step that question.

For a while now drones have been the current best manifestation of the idea that we are living in a world of consequences without warning. Of patterns recognized where none may yet exist.

At the moment we haven't completely abdicated the responsibility for drones so we tell ourselves that there is still a warm body, that we could appeal to, watching at the end of every decision to fire a missile.

But we all know that work is underway to develop systems that automate – that pattern match – those decisions.

In that way I actually think that self-driving cars are the new drones.

I've been having a running debate with the artist John Powers about the inevitability of self-driving cars and their necessity in order to ensure that urban spaces may not only survive but to thrive.

Self-driving cars may well happen but they remain profoundly weird and creepy to me in ways that other automated systems don't. It is, as systems, their complete and deliberate lack of imagination that I find unnerving.

Which brings us to the Fifth Law of Robotics as defined by me and John: That your insurance rates will always go up.

Short of divorcing all interactions between people and cars, save for air-locks in which to enter and exit a vehicle, they will be programmed within an inch of their lives to limit what they're allowed to do. Out of necessity.

Things like cars, that have mass and velocity and the ability to cause serious and permanent damage, are for good reason not given a lot of latitude.

For the same reason that I absolutely do not want to find out what the equivalent of cars spontaneously smart-mobbing to hold whatever they think a pillow fight

is, it is not difficult to imagine what it would take to launch a denial-of-service attack against a fleet of self-driving cars.

And maybe that's part of the problem.

Contrast self-driving cars with Siri which has proven itself to be a never-ending source of surprise to people. Siri seems fun because it feels like there is room to tease out new interactions; that you could make Siri in to something new and unexpected. The illusion of being able to trick Siri is real enough.

I think part of the reason we feel that way is that we rely on the notion that people are very much irrational. Not for everything, but for quite a lot of what we do it is profoundly important.

It means that there are strategies (both benign and creepy) for navigating a world of other people by being able to account for and manipulate that irrationality. It also means we preserve the ability to hide from one another.

To quote Bruce Schneier, again:

If we were designing a life form, as we might do in a computer game, we would try to figure out what sort of security it needed and give it abilities accordingly. Real-world species don't have that luxury. Instead, they try new attributes randomly. So instead of an external designer optimizing a species' abilities based on its needs, evolution randomly walks through the solution space and stops at the first solution that works—even if just barely. Then it climbs upwards in the fitness landscape until it reaches a local optimum. You get a lot of weird security that way.

There is little or no room to "play" with a thing like a self-driving car that's been built for lawsuits.

And this all points to a kind of writing on the wall that I think makes everyone very uncomfortable, whether or not we've found a good way to talk about it yet. It points to a world where we're stuck trying to make peace with the irrational pattern matching of sensors paired with the decision trees that only know a uniformity of motive.

Like the unknown high-speed trading algorithm that popped up last week and accounted for 4% of all trades. One article I've read about the event sums it up nicely:

The problem is, every exchange sees things from their own little world. They don’t see how things react outside of that world, and they have no incentive to. So when you have these complex systems interacting with each other and nobody’s really paying attention to the aggregate, you set yourself up for times ... when you’re only going to find out how the new systems all work together when you’ve got this really bad news event that nobody was expecting.

Good times.

It's not as though this is the first time we've felt overwhelmed by the consequence of the technologies we've developed. At this point we have all heard too many times about how people's minds were blown by riding the first train as it traveled a whopping six miles per hour.

It is also not the first time that we have worried that we are building a future devoid of narrative. The Industrial Revolution, and pretty much every critique of capitalism, is full of that story up to and including Francis Fukiyama's claim that history ended with the fall of the Berlin Wall.

But that doesn't mean that there isn't something new happening.

Which brings me to Instagram. Like drones and self-driving cars Instagram is just a "current best" short-hand for a lot of interrelated issues: That we have always been at war with a suspect past.

There is a lot to criticize about Instragram but I want to take issue with what is seemingly the most common of grievances: Those goofy filters.

The reason that I have such a problem with all the talk about how awful and retrograde people filtering their photos is that if we did anything wrong, at Flickr, it was letting people believe that their photos weren't good enough to be worth uploading to the site.

For a photo-sharing website I'm not sure I can think of a bigger failure. For a community website built around a medium as broad and as deep as photography to allow its members to think that there is nothing more interesting than, say, HDR sunsets is pretty grim.

And yet all it took to get all those people excited about the art and the craft of photography again – in ways of seeing the world as something more than a mirror – were those stupid filters.

Those stupid filters are really important because they re-opened a space in which people could maneuver. These are new things not least because I'm guessing that a sizable chunk of Instagram's user base was born after the 1970's and so there is no nostalgia to be asserted. The past is just a medium.

Sometimes the past is not a rejection of the present but a good and useful screen through which to look for patterns, to look for things we'd never have been able to see in the past.

We are in the process of lining the walls of the Schrodinger's box we all live in with mirrors and it may well be the first time we've gotten truly close to removing the idea of plausible deniability from our lives.

We assume that there are some very smart people at places like Google or, if you're feeling lucky, Facebook who are hard at work unravelling the mystery and meaning of all those overlapping patterns. It's worth remembering, though, that these are all companies whose purpose is to service what are basically singular and selfish motives. They are building better tools to automate already learned behaviours. Patterns.

Not too far from the center all that learning and future magic starts to get warped and abused in some very weird ways.

Pity the librarians of the future who will have to decide how to catalog the books that were programmatically written by harvesting the content farms that were themselves machine-generated to game Google's ranking algorithms.

That's the world we are all living in. The details vary from person to person but we are all trying to make sense of the feedback loop of reflective surfaces that a world gone digital is producing.

We are trying to glean the consequence of its velocity.

So, I am going to continue the tradition of ending these talks with a deliberately wooly and rhetorical question:

We have barely learned to trust one another, outside of tiny little Dunbar Tribes, let alone trust ourselves to teach computers how to interpret the motive of a stranger. We are also being forced to figure out for robots quite a lot of stuff we've never really figured out for ourselves.

What if we are pouncing on the seemingly weird stuff that the network appears to be doing not in order to correct it but as a way to dig for stories – for patterns – and to tunnel for loopholes as a way to always stay one step ahead of our intentions, of our motives.

Thank you.

And yes, we brought Roger.

This blog post is full of links.

#stories