Always be talking about the Pen...

Since doing a first Big Talk about the Pen, in Denver last March, I've done three subsequent talks

on the subject. The middle-bits and the

end are all more or less the same but each have

started a little differently. There are common themes

in all of these talks but each is different in its own

way. They are presented here not as a cohesive narrative

but because, as usual, it is the story I want to

remember.

In the time it's taken me to assemble this blog

post a colleague asked whether the Cooper Hewitt had a

digital strategy document we could share. If we had

one Seb never bothered to share it with me which is

just as well since I am mostly allergic to them or at

least choose to act as though I am. This is what I said instead and

I am including it here because it nicely synthethizes a

lot of what I was trying to get at in the talks below.

Make digital part of the executive. This is all

still so new (at least in the museum sector) that it

needs the love and care and the shit-umbrella of the

director lest the whole thing get swallowed up by

the internal politics of the organization.

Build internal capacity. Read: Hire warm bodies and treat them as your

own. This doesn't preclude third-party contracts but none of this stuff is

self-assembling. The sector has a bad habit of believing that the place to

standardize things is in the mortar, so to speak, rather than the bricks. The

results not surprisingly have ranged from hilarious to a galactic waste of time

and everything in between. Bricks are totally worth standardizing on. Mortar

itself may be something to standardize on but its application is worth paying

someone to do on a case-by-case basis.

Adopt the gov.uk motto that the

strategy is delivery.

Which is a friendlier way of saying "just fucking do it" which really means that

the people _in_ digital do not have the luxury of faffing around for six months

(or longer) because the most important thing for an organization to see in the

early stages is proof of an idea. Everything we did at CH was really hard for

people to wrap their head around in the beginning because it was so

new.

Aspirational PowerPoint slides do little to help with that dynamic after a

certain point. It was hard enough to demonstrate what we were trying to do with

the infrastructure we had (or were building) and it would have been impossible I

think without it.

Make the cost of failure as important as the cost of success which is to say

as low as possible. That is the reason for all the points above. Even if it's

just internal failures in the service of a larger project figure out how to make

them so "cheap" that everyone understands them to be the acceptable cost of

determine what success is. Then figure out how to do that in public.

...

I suppose in that regard the collections website

is/was/remains the "strategy document" you speak of.

It was the proof, the reminder and the opportunity of everything we were trying

to do. The details will be different from museum to museum but to the extent

that we all have collections and most of us think affording access to them is

important the digital manifestation of those collections is a tangible way for

an organization to demonstrate the arc of its intentions.

I guess that's why I was saying "figure out a way to do it in public" which

really means finding a way to let people work

through an idea (about the meaning and purpose of

the institution they are part of) without having

to always worry about saving or losing face.

And this is what I said before that...

press and hold to save (RFID World)

The second of the three talks was in San Diego at

RFID World, an industry conference, in mid-April. It

was a quick trip and I spoke on the weird first-but-not-really-part-of-the-conference day that so many

events suffer from. Basically it was

supply-chain and inventory management people, the

Army, the NFL (think the

Superball Twitter account pitch that Stamen did

way back in 2010) ... and

me.

I also opted to go

watch the first game of the hockey playoffs,

surrounded by what I assume were ex-pat Canadians in the employ

of the military-industrial complex, instead of

attending the opening keynote by an Army general

which is presumably why I will never be granted any

kind of security clearance. As I write this, a month

later, I see that Army-guy was replaced

by someone from something called US

Transportation Command

so... yeah.

I'd like to start with a quote by the Taiwanese author Wu Ming-Yi: Her voice infused people with the essence of a

song. It would turn into a windblown seed: you never

knew in your heart where the seed would fall, nor when

it would sprout.

This may seem like an odd

quotation for an industry conference about location

tracking, pervasive identity and generally solving for

who's on first. I like this quote because it nicely

describes some of what — and why — we are

trying to do with the Pen.

I grew up in Canada.

Canada does not have the kind

of creation myth, or foundational purpose for being, that a country

like the United States does. No one has trumped the US

when it comes to creation stories but Canada

was birthed, at nearly the same time, entirely in the

service of economics and geopolitics. Canada was created first in the service of

the merchant classes and second to ensure that a

British railroad reached the West Coast before the

Americans thus preventing them from going North. Or

maybe the other way around, but you get the idea.

Despite all the Canadian Heritage Minutes that have

been produced in the intervening years it's not really

an inspiring start. What is interesting about

Canada though is that it's managed to do pretty well

despite its generally crass beginnings. Canada is not

without problems but, at least in modern times, has

managed to create a social body that mostly

works most of the time for most of

the people.

It sometimes seems that the most critical

thing people can say about this arrangement is that it

is boring

but we'll save a discussion about

people being adrenaline junkies for another day.

It is important to mention that in Canada most

anything has historically mostly always been to the exclusion of the First

Nations for mostly everything. Canada's relationship with the First Nations,

until recent years (and still now in some cases) can

only be described as appalling and shameful. Since I started

writing this blog post the Truth and

Reconciliation Commission of Canada mandated to

tell Canadians what happened ... and to create a

permanent record of what happened in the Indian

Residential Schools

has been published. I have

not read the

findings yet but I will and so should you.

Note: This is the official Smithsonian logo but just in

case there is any confusion this is not the

official Smithsonian motto. Anecdotally, though, this

would be the most popular staff t-shirt ever printed.

I started with a story about Canada because I see

parallels in the origins of the Smithsonian. The

Smithsonian was not an American

creation but

rather the unwanted dream of an English businessman named

James Smithson. Sasha Archibald's The

Difficult Bequest: A History of the Smithsonian"

in the LA Review of Books sums it up nicely:

The Americans didn’t ask for Smithson’s charity,

and neither were they glad to receive it. Congress

had more pride than greed, and the unexpected gift

rankled: not only was it that of a reviled Brit, but

a Brit who dared demand he be acknowledged in

perpetuity. Moreover, it was earmarked for a purpose

Americans never would have chosen

themselves. Smithson’s patronage was condescending —

nothing more, one Congressman surmised, than a rich

man’s bid for immortality. Even John Quincy Adams,

the bequest’s most passionate advocate, refused to

venerate Smithson as a magnanimous patron. It was

Adams who kicked up a fuss when investors were

allowed to squander the funds (later replenished by

the US Treasury) and Adams who protested that a

national farm didn’t meet Smithson’s

stipulations. In private, however, he concurred that

James Smithson was probably insane.

But you know 169 years later the Smithsonian has

evolved in to something pretty awesome. We

have all the stuff or, more precisely, 137

million objects and counting. The

Smithsonian is a public instution with a mandate to

act as a public good and there aren't many

other cultural heritage organizations that operate at

the scale or with the breadth of the Smithsonian.

I also like to joke that the Smithsonian has the

world's largest conceptual art collection. The good

news is that there really are 137 million objects and

they are actively being cared for. The bad news is the

only real proof of this that you, as a citizen, have is a leap of

faith when I, as an employee of the Smithsonian, tell

you these things are true.

That's the larger context that the work we've been

doing around the Cooper Hewitt's much smaller collection website operates in. We

have 217, 000 objects and have been using the collection

website, and the idea the every thing of importance to

us has a stable and permanent URL, as a

device for people to have common referent

— something they can share — for

the real-life objects they may not ever be able to see.

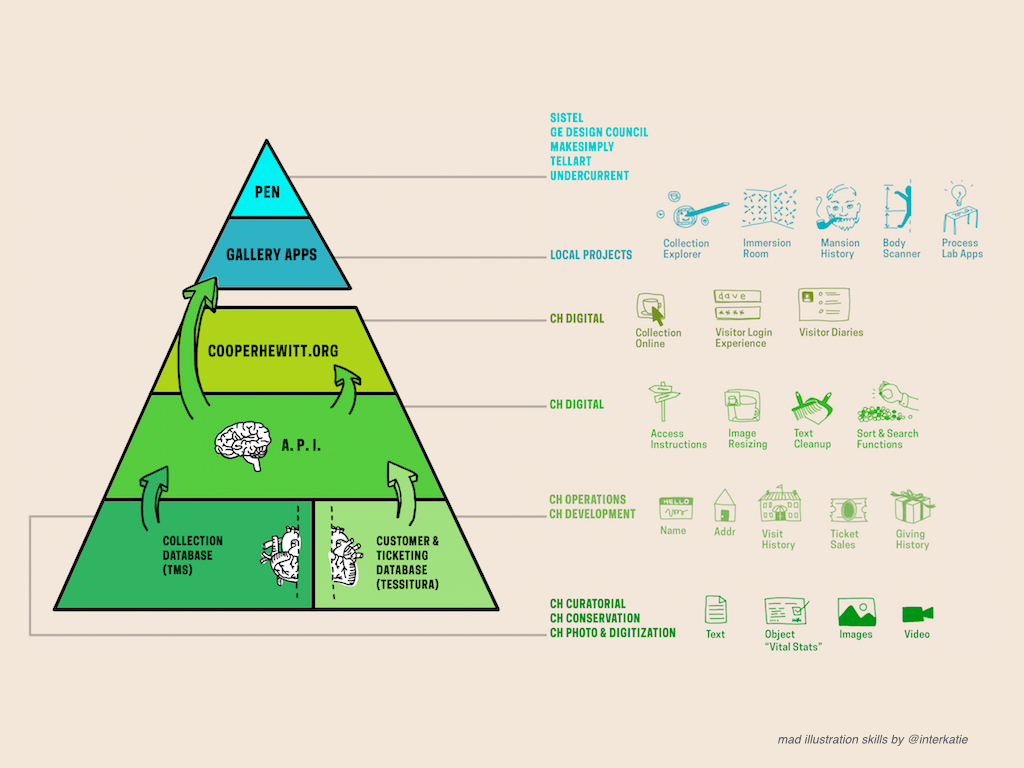

The collection website is also the scaffolding on

top of which all the work that we've done for the

museum's re-opening sits. If the macro-question is how

do you provide access to the entirety of a collection

the micro-question is: How do you provide recall for those

parts of a collection that are actually on display?

What if you could come to the museum and remember

your visit without having to spend half your time

futzing around with devices to cobble together a

half-assed and short-lived memory?

Think: Taking pictures of wall labels or taking

pictures of objects without necessarily knowing what

they are or who did them or how you figure those

things out once you've left the building.

Which is why we built the Pen.

JFDI, a love story (Museums and the Web)

The first of the three talks was done jointly

with Seb Chan, at Museums and the Web

in Chicago in early April. This was the talk to

accompany the thirteen-thousand word

paper we co-authored about the Pen and all its

related infrastucture. Seb set up the talk as follows:

- Seb talks

- Aaron and Seb argue

- Aaron talks

- Aaron and Seb argue

- Questions and answers (in the form of Aaron and Seb arguing some more)

Which is pretty much what happened. This is what I said:

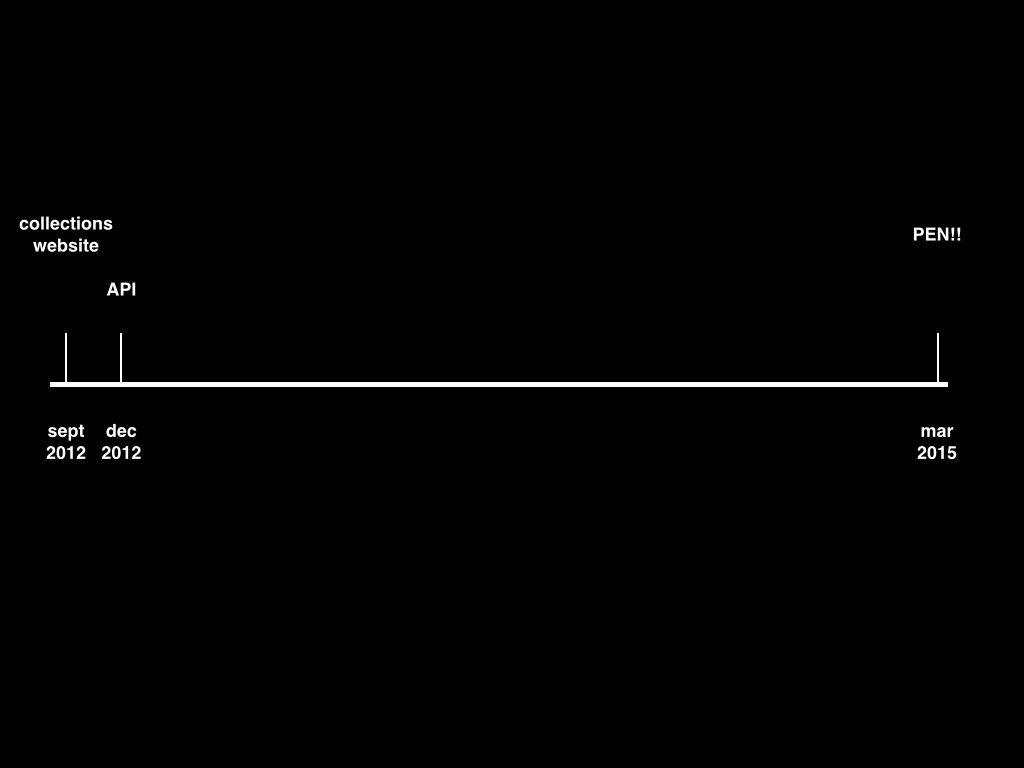

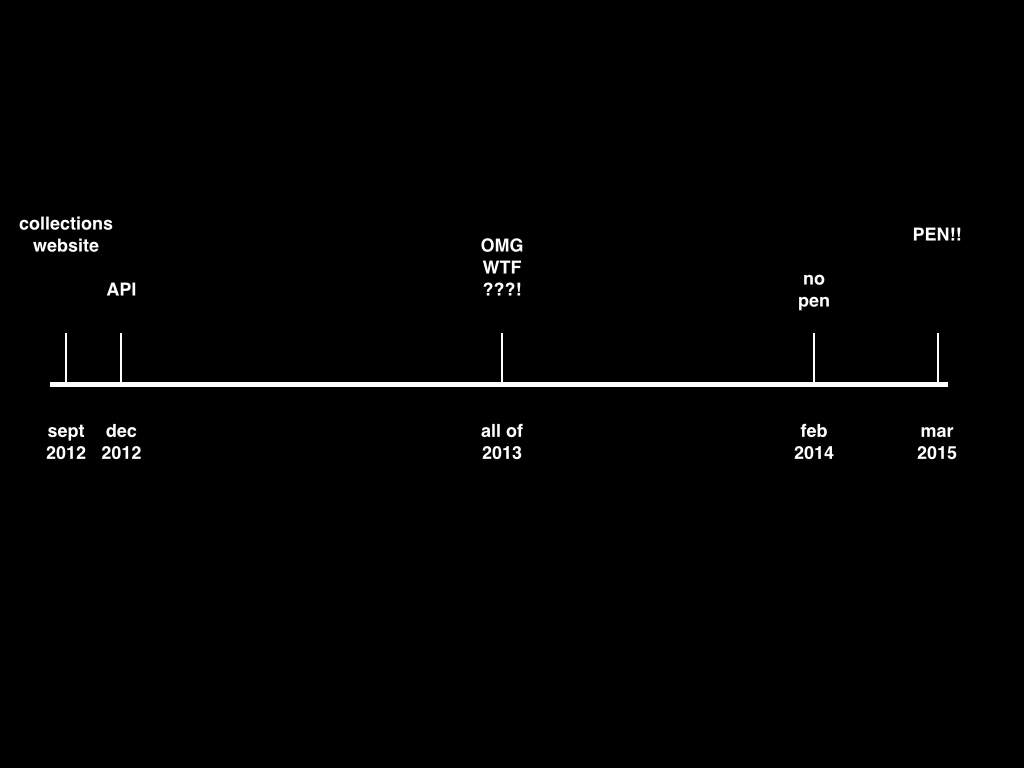

In about Decemer of 2012 we launched a public API

for the collections website. It didn't actually take

us three months to build the API. It took us three

months to decide that it should be at the top of the

TO-DO list.

At the beginning of February 2014 there was, for all intents and

purposes, no pen. If you had asked us to

demonstrate the Pen we would have only been able to

show a whiteboard marker with an RFID tag taped to it

and a Raspberry Pi with an RFID antenna and a single

hard-coded object. There were other efforts in play that

ultimately came to pass but at the beginning of the

month there wasn't much tangible to demonstrate.

This is a exagerated but not inaccurate

description of what all of 2013

looked like.

By the end of February 2014 we would have not one but two

different functional prototypes for the Pen and less

than a year later we managed to design, produce and

manufacture custom electronic hardware from scratch. (The finished pens arrived at the

museum a few weeks before they went out on the

floor.)

There are two lessons to take away from this.

The

first lesson is: It turns out that it's possible

to do this kind of thing in 2015. It turns out you can

do capital-P captial-D product design and manufacture

something in a meaningful volume — say more than

20 or even 100 and less than 500, 000 — for

a reasonable cost.

It's still really hard, requires a

stupid amount of work, no small amount of shouting at people and

a not insignificant capital investment. It was more than

lunch money but it was not an irresponsible amount of

money and if you imagine that the work we've done

might some day be deployed to every other

Smithsonian museum on the Mall then

the costs start to seem laughable.

There is no plan

to deploy the Pen on the Mall yet but we should. The

implementation details are non-trivial but

it's totally do-able (really) and would be a good way for the

Smithsonian to exercise and exorcise some of its

institutional demons and generally just be

awesome for everyone else.

The second lesson is: Don't do what we

did. Don't try to do this in a year. It's

possible but there is no valour in the

burden we took on. It's a stupid way to work but we

(the museum) had painted ourselves in to a corner from

which the only escape was to walk back out again, painting

over our footsteps as we went.

I choose to see our decision to

suffer that indignity as proof that the Pen was worth

doing but that's also the point: The Pen was worth doing on

first principles not because we have War Stories to

tell after the fact.

The reason I mention all of this is that the

constant throughout this entire process was the

collections website and the API which are really the

same thing. I sometimes hear people saying that

APIs are hard

and I am pretty sure I don't

agree with that. We launched our API three months

after the collections website and a full two-years

befor the musuem re-opened.

This is important. An API is not a finished

anything. That's the point. An API is

access to data in the service of an idea that does

something. I think there is a popular myth

that when an organization publishes an API it will

somehow magically self-assemble in to a finished

product adored and embraced by the masses.

I think that a more useful way to understand APIs

is that they exist to allow other people to build tangible

proofs without needing to badger you all the time for

the details.

Okay, this is where it gets a bit murky. I did

not have prepared notes for this talk so as I look

back, two months later, I know what I was getting at

but I don't remember any of the exact phrasing.

It was also the shout-y and rant-y and potentially

impolitic part of the talk. Impolitic because I was

trying to highlight some of the problems we

encountered working with third-party

(client-services) vendors on the project.

The problem with doing that is that, of course,

people might think I am talking specifically about the people we

worked with. Which I wasn't then and I am not now. Every single person who

was involved in the museum's re-opening has their

own set of gripes and grievances and War Stories but that's not what this is about.

I have no idea... I mean I know exactly what this

slide is about but I don't remember how it fits with

this talk...

Uh... It's a good pull-quote, at least.

Here's what happened: The Pen began life as a

concept slide.

This happens all the time. Design firms take

their clients to the far edge of the near-future as

a kind of brain-storming exercise. The point is not so much

that these concepts will see fruition but that they

will act as devices to help people articulate the

motivations and desires around a project. They help

define the narrative and the meta-project.

The problem with the Pen was that it

pointed to something that the museum wanted to be

not the meta-narrative but the narrative itself:

Recall and license. The problem with the Pen was

that the only way to genuinely achieve those things

was... with the Pen.

The problem with the Pen was that, in

2012, it seemed like something that ought to be

do-able with enough money and enough smart people

and enough hard work. The problem with the Pen was

that the realities of producing it (and producing it

for use in a museum with a heterogenous audience and

open 363 days a year) were really really complicated.

The problem with the Pen is that it was such a

good idea that we (the client) wouldn't let it

go. Eventually this made for some awkward

meetings when we would not stop asking how and when the Pen

would transition from a two-dimensional rendering in a

presentation to something we could hold in our hands

— a tangible proof. This was a complicating

factor because the idea and the aspriation was meant

to be the proof

while its execution was

always tomorrow's problem.

Eventually this disconnect reached a point where

the realities of the re-opening schedule meant that

every day the Pen was still the sum of all

possibility spaces it became harder still to imagine

completing. That's what I mean when I say: Don't do

what we did.

Or rather: Instead, foster the

institutional capacity (both for yourself and your

contractors) to minimize the wait-time between a

concept and something that works, no matter how

clunky it is. If the goal is to short-circuit the

institutional inertia that accumulates around a big

and terrifying and risky project then the goal is

really to minimize the cost of failure.

Also it helps to be able to call bullshit in

meetings. It's not fun but it saves a lot of hassle

down the road. Ask me about this slide, some day. This actually

happened and it was a profoundly

depressing moment but I am not going to get in to

the details in print. Let's just say that I was always ready to believe

that the Pen was too hard to do. I just never

believed any of the reasons I was given.

This is not about the client-services model

itself. There is nothing wrong with the

client-services model and lots of good work has

been produced under its umbrella. It is about the roles and responsibilities,

and their consequences, that museums have forged with

client-services companies.

It is about the reality that museums don't know how

to do the things they want to do and are entirely

dependent on client-services companies. It is about

the reality that museums don't even know how to

talk practically about the things they want to do

outside of magical unicorn deliverables or wishful

thinking or simply burning a problem away with

unsustainable amounts of money.

It is about

the reality that those same client-services companies can be

forgiven for not believing anything their clients say

(goals, funding, tolerance for risk) and for

ruthlessly pushing the work through a meat-grinder

tailored to their own schedules and capacities. That's

just business.

It is about the reality that if any one of those

dynamics changes there are outsized ripple effects on

all the remaining dynamics. If we're going to assign

blame or responsibility though I think we would do

well to start with ourselves: The sector has allowed

this to happen to itself.

For those of you who don't already know in a past

life I worked at Flickr for about a

million years. This is a slide I made to describe to way I

understood things to work at Flickr, circa 2009. One of the disconnects

between the way we worked at the way a lot of other

parts of Yahoo (who acquired Flickr in 2005) worked

was this idea of products

versus

features

. Most of Yahoo was instrumented to

treat features as stand-alone products and not just an

on-going extension or faceting of the original

product, in our case Flickr.

This is what most feature launches looked

like. If you were an engineer the two-to-four weeks

prior to launch were Pure Suck because everything kept

changing with less and less time to actually implement

those changes. Almost every part of the engineering

culture and infrastructure was designed to accomodate

this reality and it was a big part of our success but,

in the moment, it totally sucked.

This slide is incomplete, though.

So I think the lesson in all of this is as much

about lowering the cost of failure as it is lowering

the cost for success. The Pen was not as many, including the museum,

believed simply a question of snapping together a

suite of off-the-shelf hardware and software pieces

like a kind of cultural heritage Lego model. It was a

lot of trial and error shoehorned in to a brutal

schedule which meant a ridiculous amount of energy and

attention was spent worrying about getting something

right the first (and only) time. It's pretty great

that we pulled it off but the number of places the

whole project could have gone completely wrong and

failed were so numerous it is sort of a wonder that we

chose to do it at all.

Hail Mary passes are

exciting but they are a bad way to run a project.

The reason I started with a timeline of the API is

that in building out our own infrastructure, fast and

early, and likewise

maintaining it ourselves we have had a practical way

to build working prototypes as a means to address

unknowns and, more importantly, debate. Put another

way, we had a way to make the time and the effort

to disprove an idea or a concern or an outright

argument so low that any questions about testing it in the

first place were rendered moot.

Another way to see any discussion about the cost

of failure or success is to understand it as measuring

the cost of liability and the practice of

outsourcing risk

by delegating all

responsibility for anything that looks or feels like a

failture to third-party contractors. As a

practical matter though the cost of minimizing the

wait-time between a concept and something that

works

is very different for an organization than

it is for a contractor.

Those costs become even more pronounced when you

are dealing with something as complex, and as novel,

as the Pen was and continues to be. The following

passage is from the paper Seb and I wrote for MW and

tries to address the issue of those costs:

It is important to recognize the problems with

this model (a one-off innovation to a commodity –

ideally one which can be bought cheaper from a third

party supplier and supplimented with a support

contract that outsources liability and risk) when it comes to services-based projects

like The Pen and its ‘museum-wide’ system:

Support contracts are typically for projects

whose value diminishes over time (because on-going

development of a project stops at launch) and so

the cost of that contract, in effect, increases

year over year with fewer and fewer returns.

With support contracts very often no

institutional knowledge about the project or how

it might serve as a platform for future projects

is gained. Sometimes the only tangible skill an

institution learns, or passes on, is how to manage

contracts for service providers.

A support contract is only valid for past

work. Any additional changes or improvements incur

additional non-trivial costs because third-party

contractors not only need to complete the work but

require time to familiarize themselves with a

pre-existing code base.

Support contracts represent money that

leaves the institution and never comes

back.

These overall costs are likely to be much more

than it would cost to hire and maintain permanent

creative technical staff in a museum when

intangibles like institutional knowledge and the

ability to build on the value – technologies,

learnings, especially created by past work – are

factored in.

As a sector we have spent a couple of decades making excuses for why “digital”

can’t be made core to staffing requirements and the results have ranged from

unsatisfying to dismal.

The shift to a ‘post-digital’ museum where “digital [is] being naturalized

within museums’ visions and articulations of themselves” (Parry, 2013) will

require a significant realignment of priorities and an investment in people. The

museum sector is not alone in this – private media organisations and tech

companies face exactly the same challenge. Despite ‘digital people’ and

‘engineers’ being in high demand, they should not be considered an ‘overpriced

indulgence’ but rather as an integral part of the already multidisciplinary

teams required to run a museum, or any other cultural institution.

The flow of digital talent from private companies to new types of public service

organizations such as the Government Digital Service (UK), 18F (inside GSA) and

US Digital Service, proves that there are ways, beyond salaries, to attract and

retain the specialist staff required to build the types of products and services

required to transform museums. In fact, we argue that museums (and other

cultural institutions) offer significant intrinsic benefits and social capital

that are natural talent attractors that other types of non-profits and public

sector agencies lack. The barriers to changing the museum workforce in this way

are not primarily financial but internal, structural and kept in place by a

strong institutional inertia.

Good times.

The panopticon of taste — a cultural heritage

of plausible deniability (Data and Society)

The third and final talk was for the Databites

lecture series at the Data and Society

think tank. This one was different than the others

because I wanted to use the Pen to talk about the

weird overlap between the cultural heritage sector and

the security or surveillance state that modern life,

and its motivations,

forces in to question. The pull quote for the talk was

Why the cultural heritage community is jealous of

the NSA

so in that way it was more like

the

talk I did at the MoMA R&D Salon back in February.

I did not have narrative

slides for this talk. The series organizers encourage a short

introduction with the bulk of the event spent having

an active conversation with the audience so I put

together a set of drawings (that I made on the subways

going to and from work) to run on an automated loop

in the background as a kind of soundtrack music. I don't know how succesful it was but it's what I

did. I have included my introductory remarks scattered

throughout.

There will be video of the talk and the Q&A posted soon enough The video of the talk is online so you'll be

able to compare what I actually said with my

remembering of what I meant to say below. As is my habit, I started with a pair of non-sequiturs.

Years ago, I read an interview with the director

Hal Hartley. If you've never seen any of his films

they are punctuated by a noticeably weird and unnatural style of

speaking employed by all the actors.

Hartley talked about how, following an argument,

many people spend days and days, thinking of the

perfect come-back or rejoinder to something that was

said to them. I try to write my dialog,

he said

as if each character had that perfect come-back on

the tip of their tongue everytime they spoke.

One of the things I've been trying wrap my arms

around is the belief, in almost all large

organizations, that a project once launched will never be

revisited. This is especially true in politics or at

least perceived to be true, which might be worse.

Despite all the arguments someone else might make

in its favour there persists an institutional cynicism

that version two

of a project will never

happen.

As a consequence everyone tries to shoehorn their

part of a project in to version one

with all

the corresponding complexity and bloat and politics

you might imagine that entailing.

You can see a parallel to these phenomenom in the

way that museums think about visitation and, in turn,

visitors think about museums. In short: The belief

that everything needs to be crammed in to a too-short

90-minute visit and it all needs to be meticulously

documented as a consequence since the whole experience

ends up being like a cultural heritage version of shock and awe.

There is a spectrum (of both museums and visitors)

of course but what underlines both activities

is a belief that the museum and the museum

visit will never be returned to in any capacity once someone walks out

the door.

There is ample evidence to back up this

observation but what if you could come to the museum

and then leave with a record of your visit that didn't

demand you spend half your time futzing around with

your phone or some other device

?

How would that change the ways that you observed

and interacted with the objects on display and how

would that changes the ways that the museum interacted

with you?

What if you could go to the museum and have the

confidence of memory or recall? What does it mean for

a museum to say to its visitors We'll keep a record of your

visit and make it available for you to re-visit at

some later date

? We won't preserve it the way that

we do the objects that have been accessioned in to our

collection but otherwise it's no trouble.

Maybe that is what part of what being a museum in

2015 means. Certainly for a public institution like

the Smithsonian I think there is reason to think

that's what it should mean. Our entire purpose is to

keep things safe, after all. What if we extended that

courtesy to your visit?

So that's why we made the Pen.

Which is in many ways just a very elaborate

physical bookmarking system. People, it turns out,

like to bookmark things.

In a world where everything is measured against the

benchmark of Facebook's or Google's scale and success

our numbers are pretty humble. On the other hand if

you compare the those numbers to the numbers we used

to enjoy — attendance, dwell-time, repeat

visitation or any indication that a visitor didn't

immediately turn to dust the moment they walked out

the door — it's been a raging success.

The figure that I often mention is that, in the

less than three months since the Pen has been

available to visitors, there have been just shy of one

million act of collecting

. Which is pretty cool

considering that there are only about 700 objects on

display in the museum itself.

And of those million acts of collecting visitors

have collected 3, 900 different objects. When you look

at the numbers it is absolutely clear that most of the

things that people collect are collected from the wall

labels, rather than the interactive tables, in the

galleries. I can't be bothered to do the math to

establish whether it's really an orders of magnitude

difference simply because the numbers are so extreme.

But think about it:

Most things are collected from wall labels but there

are only 700 objects on display but 3, 900 distinct

objects have been collected.

Part of the workflow for any new exhibition

involves the curators choosing, for every object on

display whether its a loan object or one of own, up to

ten related objects from the collection. What

related means is left up to the curators and the only

criteria is that an object on the floor exists within

a larger context or institutional velocity.

In addition the curators were asked to tag each one

of those objects (on display and related) using a taxonomy

of their own choosing. And this is not meant to be

a one-off either. We do this now for every new

exhibition going forward which means we are

always supplementing and improving past work.

That people are collecting 3, 200 objects not even

on display in the galleries points to the larger

opportunity in doing something like the Pen.

Every act of collecting an object (or of creating

your own on one of the interactive tables) has a

permanent and stable URL. What that offers both the

museum and its visitors is a tangible and practical

scaffolding that affords each of those permalinks

the same possibility to serve as a resource the way

the interactive tables do in the galleries.

This is not work we've done yet nor it necessarily

obvious, easy or inevitable. We have been a little

busy just making the basics work but we have always

done that work with an eye towards what it makes

possible next.

During the question and answer for this talk

someone asked me what we thought our visitors would do

with all of the stuff they collected. My answer to

that question has always been: We have confidence that

our visitors will figure out what to do with it on

their own terms and for their own reasons.

The list of things that you might hang off any one

permalink for an object collected is mostly limited

only by the time and typing required to implement it

so I don't get hung up on any one specific thing. We

should do all of it.

The bedrock of cultural heritage is debate and

nuance. Neither of those things square well with the

demands of architecture nowhere better seen than in

the practice of asking people with decades worth of

theory and practice to reduce their knowledge to a

scant paragraph taped to a wall next to an object.

Rather than trying to usher in a paradigm shift in

the realities of physical space the Pen, and all those

permalinks, offers a middle ground. There is still a

primacy in the object itself (even if that object is a

device for a larger social gathering or event but now

it shares that space with recall) with the safety of

staying present in the moment confident that it might

be revisited later, with the luxury and the

convenience of being able to choose what later

means.

Maybe later

also includes the ability for

museum visitors to contribute to the meaning of an

object or an event. As a design museum we increasingly

traffic in things that are literally hollow shells

without the software or the data that runs

them. Privacy details aside, what

if you could donate the data your Nest thermostat

collected to sit alongside the same hunk of metal and

plastic (and concept sketches) that we have sitting in our collection? What if

there was a way for you to participate in the meaning

of that object?

Which is all fine and good for museum objects,

right? I like to think so. This is what the fruits of 2015, all of this

amazing technological capacity to suspend time, make

possible. The batteries not included

part of that

equation though is the social contract around that

kind of recall.

Pretty much everything I've just

described, done to foster learning and understanding

in and of the arts, is also being done by big

companies and intelligence agencies alike. If Edward

Snowden is to be believed then it is being done by the

latter at a scale and with a reach that sometimes

exceeds imagination.

Let's assume for the sake of argument that the

stories told about the NSA's ability to record and

recall history are true. Let's assume that their

ability to weave tapestries of meaning out of nuance

and innuendo is unparalleled. When all of that attention is directed

at any one individual they might be forgiven for

thinking the whole project is a little sinister.

When you remove the sting of present consequences

the ability of these organizations to record your

visit

so to speak starts to look not just

attractive but beneficial in the long run. In some

distant future where our present is just a shadow of

its current concerns they will thank us for our ability

to preserve ancillary materials associated with a

subject and of instrumenting the cost of following

hunches and generally spelunking

through the mass of data to the point of seeming negligible.

These are not the issues that governed the Pen, or

the museum's re-opening, but

they are the places where the Pen overlaps with the

present. These are not tomorrow's problem.