time pixels

Last month I was asked to be one of the four keynote speakers along with Piotr Adamczyk, Sarah Barns and Nate Solas at the New Zealand National Digital Forum. New Zealand is a far away place for most people but the quality of NDF and the loveliness of everyone involved (not to mention New Zealand itself) means that if the opportunity ever present itself, even remotely, you should absolutely-no-questions-asked go! The conference was held in Wellington and I stayed a few extra days to attend THAT Camp and meet with folks before catching up with Nate in Australia. From there we rocketed through Hobart for a quick visit to the Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) before spending a couple of days with the good folks at Museum Victoria, in Melbourne, and the Powerhouse Museum, in Sydney.

There are so many people to thank that I am hesitant to start for fear of forgetting someone but the short list will always include: Matthew and Chris and Andy and Courtney and Adrian in Wellington; the Richter City Roller Girls for trying their best to get me a t-shirt even though I was too stupid to notice that hotel rooms still have phones in them; the receptionist at the hotel in Hobart for telling us about the Tasmanian International Beer Festival when we arrived and asked where to grab a drink; Tim and Ely and Ely and Kate and Ajay in Melbourne; Paula and Dan and Nico and Luke and Matthew and Kier in Sydney. Also, Slowpoke in Melbourne and the courtyard at the Powerhouse for being little oases of free wifi in cities with otherwise dubious network availability. I commented to someone, during our stay, that although it was actually fine to go an entire day without checking email or doing other business on the network it only reinforced the feeling that I want to live in that other world, the one where the internet is always present.

And Nate for being a righteous tour

buddy on top of his already normally clever and awesome self.

This is what I said. Mostly. What follows is a product of the talk I gave in Montreal, in October; what I said in Wellington and what I said later when I delivered the same talk in both Melbourne and Sydney; and countless conversations I had before, during and after. Thanks to everyone involved, especially everyone who sat through the talks and took the leap of faith even though the drop was probably a little further down than I let on at the start.

Some of you may notice that the talk isn't marked up with links like so many others posted here. They will come. It's been a whirlwind couple of weeks (months, really) and now I am settling in for some quiet time. I will update things when I put the public face on again but, until then, it's just words. Lots and lots of words. So many words...

The author Kurt Vonnegut once wrote that the first rule of public speaking to never apologize. So I am not going to apologize. I would, however, like to take a moment to thank the organizers of the National Digital Forum for inviting me here to present this keynote. I have had many opportunities to speak publicly over the years but I still think that keynotes are special.

Maybe there are people who have become blasé at the opportunity to come and speak about, sort of, whatever's on their mind but I hope to never be one of those people. I think it is a great compliment and kindless for you to have extended that hand to me, today. Thank you.

So, hello everyone. My name is Aaron. I am from the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum. For those of you who don't know much about the Cooper-Hewitt the short version is that: It's the place Seb Chan went to, when he left Australia.

The longer version is that we are part of the Smithsonian. We are not in Washington like the other Smithsonian museums. Instead we are located on the Upper East Side of Manhattan in Andrew Carnegie's old mansion. The Cooper-Hewitt became part of the Smithsonian in the late 1960s and our history is of a collection with a strong emphasis on the decorative arts put together over the years by the Hewitt sisters. In the 1990s we took on the mantle of being the captial-N national design museum and we've been working through everything that means, since then.

We are closed until 2014 and are renovating the physical space as well as the digital infrastructure that increasingly holds it all together. My title at the Cooper-Hewitt is Senior Engineering in the Digital and Emerging Media department so part of my time is spent helping to imagine what it means for the Cooper-Hewitt to be native to the internet and the rest is spent figuring out how to build it.

This is not a nuts and bolts talk and I am not going to talk very much about the specifics of the work we're doing at the Cooper-Hewitt. I want to talk, instead, about the larger context in which the work we're doing is situated and to try and see through some of the dazzle paint of our daily burdens to imagine the future.

Earlier this fall I was invited to participate in a design workshop in Detroit, called To Be Designed. The goal was to produce, from scratch, a printed catalog of "near future" consumer items. In the early briefs it was often discussed as a kind of near future SkyMall which in retrospect was maybe not the most useful of ways to talk about things.

We very quickly got stuck in a kind of quicksand about whether and why we were promoting a questionable form of low-brow and generally crap consumerism. Were we simply doing a classic client-services design exercise or were we trying to perform a political act? Personally I didn't have a problem with the SkyMall trope because I took it to mean as Julian Bleecker, the workshop's organizer, said those technologies and processes that used to be considered magic but that have become so cheap and so readily available that they make possible something like Sky Mall to exist.

So the exercise was to think about what a future SkyMall might look like from today's eyes; to think about the kinds of things that might have plausible manufacturability in the next five years or so.

For example, it's now possible to buy little USB thumb drive cufflinks from the real life SkyMall. I think they only have about 2 gigabytes of storage which is already pretty amazing but it's equally easy to imagine that inside of 24 months they could have 2 terabytes of storage. Which means most of us could walk around with our entire collections on our wrists.

I'd like to approach some of the issues we're all wading through, in the cultural heritage world, with a similar kind of sideways glance.

So, it is with great pleasure that today I am able to announce that the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum has acquired the War on Terror for its outstanding achievements in the field of service design. Really.

Wikipedia defines "service design" as:

...the activity of planning and organizing people, infrastructure, communication and material components of a service in order to improve its quality and the interaction between service provider and customers. The purpose of service design methodologies is to design according to the needs of customers or participants, so that the service is user-friendly, competitive and relevant to the customers. The backbone of this process is to understand the behavior of the customers, their needs and motivations. Service designers draw on the methodologies of fields such as ethnography and journalism to gather customer insights through interviews and by shadowing service users.

We think the War of Terror has not only reshaped our very notion of service design methodologies but also pioneered new and challenging experience design paradigms. We have been in extensive negotiations with the United States government to secure the necessary rights to create rich and engaging user experiences in the museum to support this most important of contemporary design interventions.

Okay, not really. But as design fictions go it's a great way to explain to people why I chose to come at work at a design museum.

It is a good time to be a design museum. It's a good time because while acquiring the War on Terror is one of those things that seems like an elaborate joke at first (because it is... sort of) the funny-ha-ha gradually settles in and starts to seem like something plausible and almost inevitable. Someone probably should acquire the War on Terror. Someone probably will. It might as well be the Smithsonian, given our mandate.

We traffic in things that, whether they are meant to exist in the real world as mass-produced objects or as conceptual ephemera, have a diversity of histories attached to them. We traffic in things that we don't necessary know how to collect yet, in part because of their nature as things devoid of a single narrative motive.

I used to tell people that Flickr's great unfair advantage was that we trafficked in pictures. That our base unit, the thing that we used as a jumping off point for all those other things the site does, from groups to geo to tagging and beyond, is a still image. A thing that if 10, 000 years of recorded and anecdotal history are to be believed we are hard-wired to respond to.

Look around you. See all of this stuff? It's all designed

. That's what we, as a design museum, get to start with. And it's not just the things themselves but increasingly we are understanding that the process by which these things are brought in to our lives is just as important. As a design museum we are being forced to consider what, and how, it means to collect more than the just the shiny physical thing.

At some point in the not too distant future I imagine that we'll start collecting all these museum "experiences" we spend so much time creating. If those aren't design – a deliberate and manufactured product that exists to service more than the whim and folly and intellectual curiousity of an individual – then maybe we need to jettison the whole notion of design altogether.

Or start asking some serious questions about what we're trying to do in museums.

On some levels, you could reduce this entire talk down to a very simple question: Why are keeping any of this stuff? Or rather: If we as public institutions, or even private ones that wish to bask in the warm fuzzy glow of the public "trust", can't figure out how to provide access to all of this stuff we're collecting then what exactly are we doing?

We tend to justify these enourmous and fabulous buildings we create to showcase our collections on the grounds that they will, sooner or later, be the spotlight that embraces the totality of the things we keep. Yet that doesn't really happen, does it? Every museum has these vast and cavernous archives of stuff hidden from view which starts to make me wonder why we're keeping it all and, more grimly, makes me question the function of the museum buildings themselves.

I happen to believe that what we do is a luxury afforded to us by our peers. Not our professional peers but everyone else, out there. The rest of the community; society at large; the people we struggle to share life with and with whom we celebrate when we figure it out. We are afforded the responsibility of keeping safe our cultural heritage because all those other people who don't live inside the hula hoop think it's important.

I am fine with people who want to establish and fund their own private collections. That's their business and good for them if that's how they want to spend their money. I also think that it's in everyone's interest to invest in time keepers

(because that's what we are) whose baseline is the public good and not the folly of shareholder profit or the whims of private donors and collectors.

But I also believe that with that position of trust comes a responsibility to provide genuine and meaningful access to our collections. Or at least to get up every day and make a good faith effort towards that goal.

This is an argument that I've made before and I will get in to some of the specifics shortly but today I'm going take a bit of windy road to get there. It's very much the scenic view with a few nerdy cliffs along the way. Don't worry about getting hung up on the specifics. The important parts are the changes, so to speak, in the air pressure outside and the soundtrack music of the wind around us.

I am going to start by talking about artisanal integers. It's a leap. It's probably going to seem, to some, like another elaborate joke. Because they are.

But, like the idea of acquiring the War on Terror, they're a very useful kind of intellectual bungee jumping: They are a device to see how far down the rabbit hole you can go with some degree of confidence that there is always going to be a trap door back out again.

One of my favourite quotes ever is from Jack Schulze, a principal at the London design studio BERG (and great, tall and lovely, swear-y man). He said: No one cares what you do unless you think about it and no one cares what you think unless you do it.

Which mean there's a backstory to tell in order for any of this to make sense. It's a bit involved because the story has been telling itself through a variety of projects I've been building to prove (or disprove some) of these ideas, with working code.

The first stop along the story is the building=yes project. This is something I did in 2010 when I began to wonder how many building there were in the OpenStreetMap project. At the time I thought there were about 27 million. It turns out there are, as of last month, closer to 67 million buildings.

For those of you unfamiliar with OpenStreetMap what 67 million buildings means is that each one of those buildings was added to the OSM database by first creating four or more points (or "nodes") and then grouping them in to a set called a "way". Each one of the nodes and the way are assigned a unique ID and the way is tagged, literally, "building=yes". There's often not much of the way of metadata – a building name or the architect who designed it – but they do all have accurate geographic tprints.

I built myself a website to catalog each one of these buildings, isolated from all the other things in OSM, because while 27 million (nevermind 67 million) is an impressive number I still couldn't really imagine what that meant. It was so big that there wasn't anything to hold in my hand.

I mentioned that each one of the buildings – the ways – had already been assigned a numeric ID by the OSM database. I went ahead and generated new IDs for each building, starting at 32 bits plus one. I did this because I wanted to parent each one of these buildings with an existing gazetteer of place names called Where on Earth, which already uses 32 bit IDs and I wanted to ensure that there weren't collisions between the two datasets.

I wanted them to hold hands.

Sort of like a baby monkey holding a baby tiger.

Fast forward a bit to about a year ago when I started working on a project called Parallel Flickr.

Parallel Flickr is an exercise to create a living breathing archive of my Flickr photos. Not a replacement but something other than the usual cold storage backup systems we've all grown used to. It was also an exercise to work through the idea of what it means for an individual to take a more active responsibility in archiving the digital bits that are left all over the internet.

The model behind Parallel Flickr is pretty simple: Individual photos belonging to one or more users, are backed up, along with the photos they've faved. Raw API responses used to retrieve metadata, which are also stored as text files. Those files are used to create a local database that runs the site.

Each user's contact list is also archived. This means that by using Flickr itself as a single sign on service – kind of like the way Facebook Connect works – there's a way to honour the privacy settings for each photo. It's certainly not a future proof way to archive something like Flickr (it assumes that the service is still around to act as a validation service) but it's at least a step towards imagining how we might preserve some of the social interactions around the services that have been burrowed so deeply in to our lives.

Parallel Flickr is meant to run alongside the site itself and be a ready alternative if ever the worst happened and Flickr shut down. The really important piece of this setup is that it mirrors are the URL structures of Flickr itself. The domain name might change but otherwise all the URLs should just keep working.

One day I was talking with my friend Mike about all of this. He asked me: Does it make more sense for me to run a single instance of parallel-flickr for my five friends or should they all run their own copy?

The beauty of Parallel Flickr is that you can do either, or both. If you and I merge our copies of Parallel Flickr and we encounter collisions across numeric identifiers it just means that we each have a copy of the same photo.

What that means is that it provides an avenue to start to rebuild the network (the larger mess of a thing we know as Flickr) organically one instance of Parallel Flickr at a time. It means that not only can one copy of Parallel Flickr hold hands with Flickr, the service, but that multiple, disparate copies of Parallel Flickr can hold hands with each other.

This slide used to just say "Flickr Commons" but since I am in Australia now I changed it a little because George Oates, a friend and former colleague at Flickr, is not only the woman who started the Flickr Commons project but also one of your own. You should be proud of her. For most of the people who've worked at Flickr the Commons represents the single best, most important thing we accomplished while we were there.

Occasionally, I get asked how you might go about archiving – preserving – all of Flickr itself. The answer is pretty simple: You buy the site and you run it. It's the only way to preserve the privacy settings. The alternatives are to expose a lot of stuff that was added to the site outside of public view, on trust, or to capture a tiny subset of what the site is.

Earlier in the year I co-authored a paper about some of these problems with Ryan Donahue, now at the Met. One day I was talking to George about both the paper and Parallel Flickr and she offered a novel suggestion: What if you started to archive Flickr by first capturing all the photos in the Commons but then extending the embrace by archiving the photos of all those people who had participated in the Commons; all those people who had left tags, or comments or simply just favourited a photo.

I don't know whether it's an approach that would finish in creating a meaningful representation of the site but it's a start and I think it's intriguing for a couple of reasons.

First, it would be a better reflection of the diversity of photographs and motivations on the site by wrapping the Commons is the big fluffy sweater of all those crazy beautiful and wonderfully stupid photos that people chose to share with one another.

Secondly, it suggests a whole new way for cultural heritage institutions to think about preserving services as big and as complicated as Flickr. Let's start by imagining a library or an archive choosing to tackle the problem, or even a subset of it: Only those users that have taken photos geotagged in Australia or New Zealand, for example. If that were to include me – since I've taken photos in both places now – not only would that institution have the photos specific to their area of interest they would start to also collect the context in which my photos exist, namely all those other photos from New York and San Francisco and Montreal.

We've never been able to do that before.

Further, imagine that institution also offered to honour the privacy settings of those photos with the caveat that as soon as Flickr wasn't around to act as a single-sign-on service then private photos would go dark in exchange for being able to release them back in to the public domain after, say, 70 years.

I'm willing to bet that if those were the rules you'd see a rate of participation approaching 90% or higher.

It's not just the Commons either.

This is a photo of Penelope Umbrico's 1000 Suns project which takes as its raw material other people's photos from Flickr. I actually have a number of issues with this project but I'm not going to talk about them here. Come find me in the bar, afterwards, if you're interested and I will dazzle you with some epic table pounding about it all.

Also, there are still moments when I'm not certain that my criticism is internally consistent with some of the things I'm going to mention during the rest of this talk.

Instead I mention it because since the artist keeps copies of all the original photos complete with their Flickr photo ID it means that there's a way (in most cases) to track down the original photographer, so it becomes interesting to imagine using those 1000 suns photos instead of the Commons as the vehicle for seeding an archive of Flickr.

And the really interesting part for me is that if two institutions (or individuals) were to undertake their own partial archiving of Flickr separate of one another they could – assuming they're using a functional equivalent of Parallel Flickr – easily merge them in a single archive.

They can each tackle a piece of the problem without assuming the burden of the whole. They could hold hands with each other in a way to points in a maybe-sorta-kinda direction for how we tackle the very real mechanics of how we preserve these enormous digital and very social enterprises that define contemporary life without forcing any single actor to try swallowing the ocean.

It also forces institutions in to actively accepting contributions from the users of those services themselves – of me being able to merge my instance of Parallel Flickr with yours. Or of articulating a reason why they shouldn't at least not in the context of a social service. I am genuinely curious to hear someone make that argument successfully since I've never able to myself; not without imagining a scenario where an institution loses all credibility in the process.

In addition to creating a shadow copy of my Flickr photos I've also been doing the same for my Foursquare checkins. It's a project called "Privatesquare".

There's an important difference between the two projects. Parallel Flickr sits patiently in the background and archives photos after they've been uploaded to Flickr. Privatesquare, in addition to being able to pull things down from Foursquare, also has the ability to act as a checkin client but a checkin client that records the event locally before telling Foursquare about it.

What that means is that, as often as not, I only tell Privatesquare where I am. Those signals are never actually broadcast back out to the Foursquare servers.

I've taken to calling this a "looking glass archive". One of the downsides to this approach is that there's no easy way to merge two separate instances of Privatesquare (as you might with Parallel Flickr) because there's no guarantee that every checkin will have its own unique Foursquare ID.

Instead you and I will each have our own databases of locally created IDs which share the very real of chance of colliding. This is, I want to point out, not very high on the list of pressing problems we face but it is a puzzle and it's one I found myself thinking about in bed one morning.

As I lay there, trying to wake up, I thought to myself: Oh, I know.

Instead of creating IDs locally what if, as a user checked in (to Privatesquare) I created a little static map of that location and uploaded it to Flickr and used the freshly created photo ID as the checkin ID.

Once you've gone down that road it doesn't take long before you start thinking that you could simply upload 1x1 pixel images, deleting them right afterwards, and treat Flickr as a de facto ticket server. In the cloud, as all the cool kids say these days.

Everyone who still works at Flickr thinks I am evil for loosing this idea on the world.

A few days later I was sitting with my friend Mike in a coffee shop in San Francisco's Mission District telling him the story I've just told you. It was mostly just a funny story betwee friends but it seemed then – and still does – like a problem on the horizon that we may actually need to sort out sooner than we think.

As people are bumping up against some of the concerns around centralized services (basically anything and everything that Facebook touches) there are more and more efforts being made towards decentralized services. Things like Privatesquare which generate identifiers – pointers – that will increasingly work their way in to the rest of lives.

Things like Privatesquare that we may well, one day, want to use to create something new by mixing and matching the parts but that will be hobbled by their inability to make sense of which pointer points to what. By their inability to hold hands.

Mike looked at me for a minute and then said: So, are you suggesting that we need something like a centralized "integer as a service" platform? The short answer was, and remains, "no" because that would kind of silly. The longer answer is "maybe, yeah" for the reasons I've outlined above.

It's how Mission Integers was born. If you don't know anything about the Mission District in San Francisco it's everything you've heard about hip and gentrifying bespoke trendiness given form so mostly as a gag Mike suggested that rather than any old unique integers there would probably be a demand for hand-crafted artisanal integers.

So yes, we were absolutely taking the piss and at this point the whole project was nothing more than hot air. It's also worth pointing out that there are a number of existing schemes for creating unique identifiers already. The UUID scheme, for example, is actually pretty great but it has a few problems that I'd like to avoid is possible:

- They're very long strings (a mix of alphanumeric characters and dashes) which makes them both ugly and less efficient than numbers to index at the database layer

- Although just about every database and programming language implements the code necessary to create and store UUIDs it introduces yet another loop in the dependency chain required to use them. Numbers have the very real advantage of being the base unit in all computers.

- There are a variety of techniques for encoding and decoding large numbers in to short strings, without the need for a separate lookup table. Short codes for unique IDs are really a kind of user experience icing on the cake but there is something to be said for sweating those details.

You could use UUIDs, easily enough, to accomplish much of what I'm describing now but I wanted to spend some time trying to overcome the problems I've just outlined.

That's pretty much where we left it – the subject of coffee breaks and late-night drinks – until I decided to join the Cooper-Hewitt and move from San Francisco to New York and more specifically Brooklyn which has an even higher density of hand-crafted, artisanal bespoke-ness than the Mission.

So I decided to create a sister site for Mission Integers called, not surprisingly, Brooklyn Integers.

A couple days before I left San Francisco Mike and I sketched out a plan for how our respective foundries might each issue new integers without any overlap but it's important to remember that we hadn't actually built anything yet. That came about three weeks in to my new job when I sent Mike a text message over lunch saying that he needed to actually get Mission Integers off the ground and answering requests or that I needed to get Brooklyn Integers working. Or both.

Because I needed them for work.

And this. This is the neighbourhood I moved to, in Brooklyn. It's called Gowanus Heights and it's a neighbourhood that didn't exist before we got there. About a month after we arrived I spent close to 20 minutes, one afternoon, trying to figure out what neighbourhood the various location-based web services thought my street corner was part of. I still don't know.

There aren't that many neighbourhoods to choose from so eventually I just created one. This is just an anecdote so don't worry too much about how the social geographies of New York City fit together but if real estate agents can do this then why can't I? This is how culture is made, right?

I didn't just name the neighbourhood. Along with friends we defined its boundaries and created all the necessary metadata files so that other people could reference Gowanus Heights.

And we gave it a Brooklyn Integer, of course.

Remember how I started by talking about the desire for buildings in OpenStreetMap to be able to co-exist peacefully with the Where On Earth gazetteer? Gowanus Heights does the same thing.

Technically, it's all still hand-waving since WOE doesn't use artisanal integers but if they did then assigning my neighbourhood a unique Brooklyn Integer would offer the ability to reliably say that it's ID is a child of the WOE ID for Brooklyn itself, without worrying that its ID was also an historic town in Outer Mongolia.

I mentioned that Mike and I had talked about how we'd both be able to run an artisanal integer foundries without stepping on one another's toes. It's pretty simple really. Our respective databases increment numbers by 2, and we respect our initial offsets.

Mike is a partner at Stamen Design which is located at the corner of 16th and Mission, sort of ground zero for the Mission District. Because Stamen is located on the right hand side of the street – at 2017 – I get the odd numbers (since Brooklyn is on the right hand

coast) and he gets the even ones (as San Francisco occupies the left hand

coast).

Which prompted a few people to ask: Were we trying to corner the market on integers?

The answer is absolutely not. I always assumed that we could keep going by calculating the amount each foundry increments by as the total number of foundries times two. If we all honoured the offsets we'd be fine. The goal wasn't to issue every number, just unique ones.

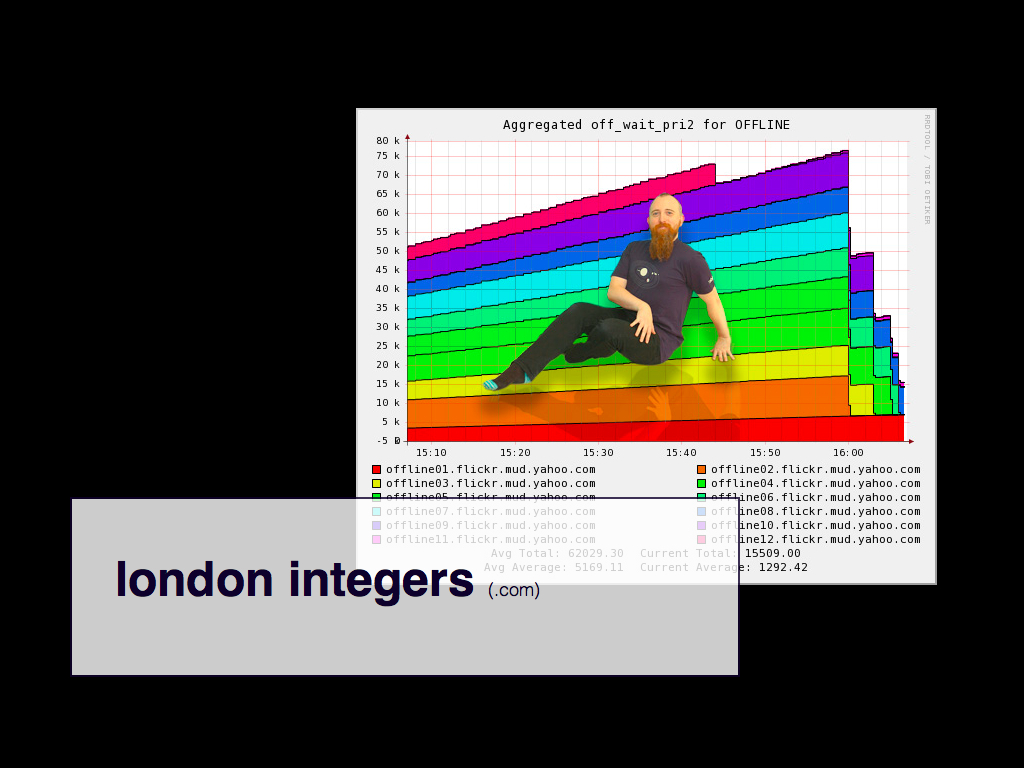

For example, Dan Catt came along and created London Integers.

Dan decided that his first integer was going to be the largest number that either Mike or I had minted, plus one. Dan reasoned this would give us enough time to update our code because rather than incrementing by (n) times two he was simply going to claim every number, after his starting point, that is divisible by nine.

So where people had inferred a set of consequences in mine and Mike's actions (that we were trying to corner the market on numbers) Dan had actually done it. Or at least done a tenth of it.

In the midst of all this my friend Nelson Minar decided to try and solve two of the very real problems with artisanal integers as they'd been implemented thus far:

- That all parties producing integers needed to be aware of one another and to honour their respective offsets.

- That there was no way to infer from a given artisanal integer what it's provenance is, or where it came from.

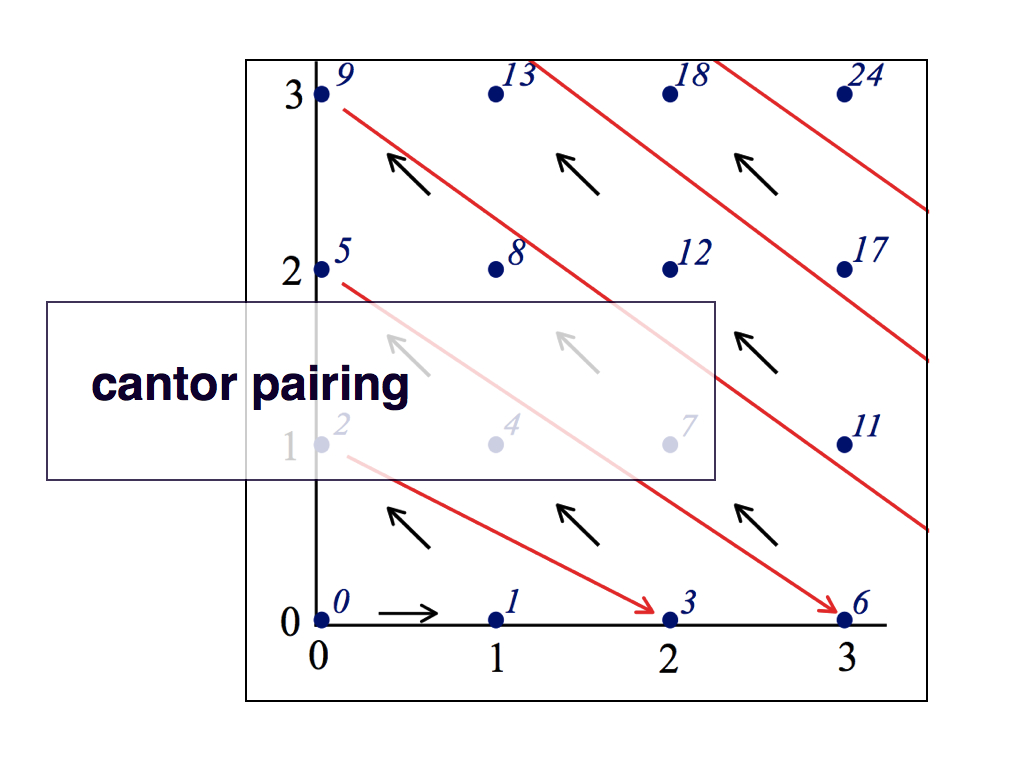

Nelson did this using secret magical powers better known as "maths", specifically a technique known as Cantor pairing which is a way to generate a number based on a fixed number for a foundry (or artisanal integer provider) and the most recent, largest integer it has produced.

It's pretty elegant but it does have a serious flaw. Because of the way the offsets work when calculating integers you effectively collapse the enormous number space we enjoy today (the 64 bit number space) back down to what we had to work with in the early 90s (the 32 bit number space).

That's not awesome for a service that claims, as Brooklyn Integers does, to have infinity on its side.

Nelson has since proposed resolving this problem by saying:

With the current simple even/odd split for two foundries, we can generate 2^63 integers before running out of room, so many it’s hard to call them artisinal really. But with the Cantor numbering we hit 2^64 much sooner: it will be site #3,327,948,883 generating its 2,746,052,116th number that is 2^64. Or to put it in plain English, every foundry gets to generate about two billion integers before hitting the limit. ... I submit the practical solution is to pick a large fixed number of integer foundries, say 1000, and simply have each foundry agree to generate numbers in the sequence (eg) 1003, 2003, 3003, 4003. It lacks elegance but is probably sufficient to meet demand.

So, a thousand foundries. Which is over three times the number of countries on the planet, right now. In theory we could just petition the United Nations, or maybe someone like International Civil Aviation Organization, to operate the Ministry of Numbers on a per-country basis. It would probably work, too.

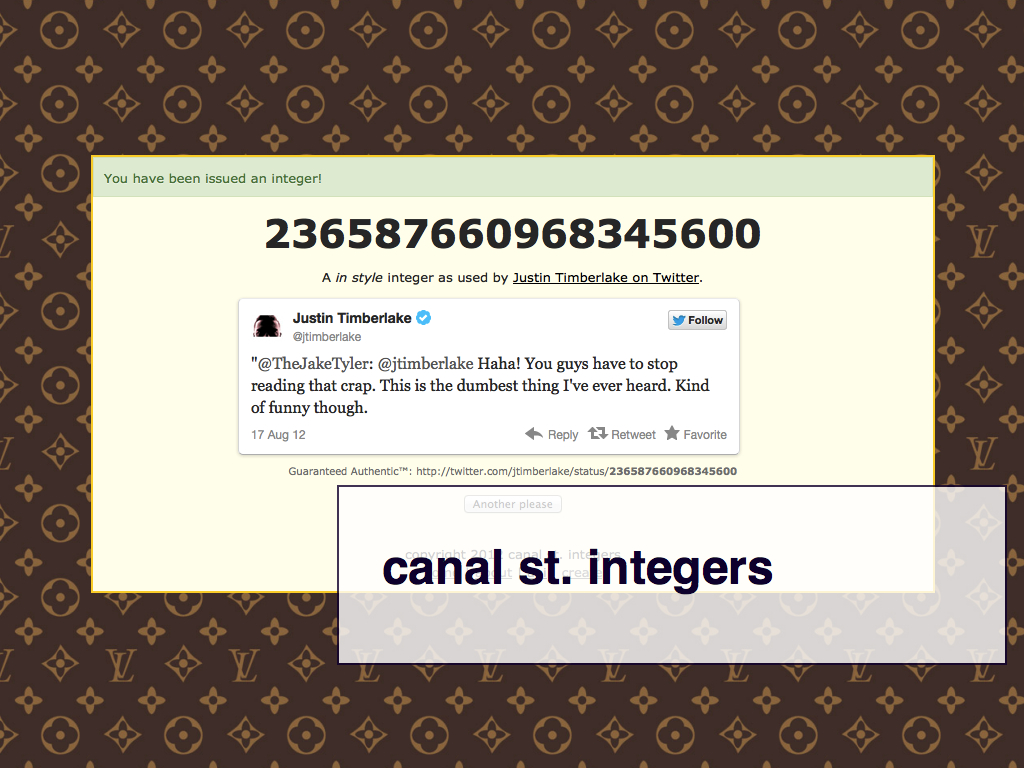

Or we could simply adopt my friend Matthew Rothenberg's solution which is to issue cheap knock-off integers harvested from the Twitter message IDs of famous people.

There's one last swallow of deep water before we come up for air: Spacetime IDs.

Spacetime IDs are just a fancy name for points along a Hilbert curve. Hilbert curves are sometimes called a "continuous fractal space-fitting curve" which is confusing math talk for a very efficient way of storing points, and of finding their neighbours, in a two or three (or more) dimensional space.

People who make maps and have to deal with spatial queries love Hilbert curves because it makes an otherwise complicated query simple and elegant.

I like them because they allow you to compute a unique ID, given x, y and z variables, that can also be decoded at a later date to see the values that were used to compute it.

I first learned about Hilbert curves when I still worked at Flickr and spent most of my time thinking about geotagged photos.

There were never any serious plans to use Hilbert curves at Flickr but it was definitely an intriguing way to think about encoding the semantics of a photo – specifically a latitude, longitude and a timestamp – in its identifier.

Careful readers will have noticed that everything I've just described also exposes a glaring and irresponsible security hole so it's always remained more of a thought exercise than anything you might mistake for a practical solution.

But, consider this: What if we replace the timestamp with the object ID of a thing in our collection?

This is still a bit of a work in progress, and the paint is still wet, but I think this could prove incredibly useful for institutions that collect things which are produced in multiples. Institutions like design museums, say.

What if we could issue unique identifiers for every instance of a design object. A coffee maker for instance or, if we want to side-step the privacy question altogether, fire hydrants. Each fire hydrant would be able to exist as an atomic, addressable entity but still be able to point back to their heritage, so to speak, both as physical (geographic) and cultural objects.

Or what if we replace object IDs with person IDs for graffiti artists and played the same trick with the many tags they leave around the city? That could be interesting.

None of these are bullet proof solutions nor are they trying to be. They are each, in their own way, efforts to work through the very issues that make them not bullet proof.

Artisinal integers and spacetime IDs are MacGuffins. They are a MacGuffin's MacGuffin.

They are each an effort to work through the actual mechanics of what it means for things to be present – to be reliably present – on the network. To be present and accountable in a way that gives them gravity and mass around which the rest of life can orbit, in confidence.

We talk big about playing the long game but we don't, or haven't, really followed through on that rhetoric when it comes to our collections and the network.

I always try to think about this in terms of the network and not the "web". It's hard to imagine the web going away these days but stranger things have happened, I guess. The network – the internet – is forever. Assuming that, like me, you think the network is here to stay. If you don't then none of this is really a big deal. It's a baseline.

The whole point of putting our collections online is so that they will be there in 50 years. In 100 years. They will still call back when addressed because that's, I thought, the business we were all in keeping this stuff.

Ours should not be to pre-vett every possible scenario or use case or association of our collections along a fixed linear history or if it is, it shouldn't be at the expense of the future. If that's what we're doing I will be the bad man and say that we have reduced our cultural heritage to little more than a monoculture.

Deep breaths.

Before we go any further I just want to quickly mention that I am not suggesting that we build a Borgesian 1:1 mirror world map. That pursuit has its moments but they are not what I am talking about today.

If anything what I am suggesting is more like Benoit Mandelbrot's map of England which keeps getting bigger as you measure it. I am also not suggesting that this is what we should be doing but I do think that fostering an expectation that we could imagine doing something like it, when necessary, is important.

This is why.

This is a photograph of a warehouse equipped with robots from Kiva Systems. Kiva was purchased by Amazon last year. A year or two before that Amazon purchased the online shoe retailer Zappos as much for their expertise in warehousing as for their customer base.

These warehousing systems, and the robots that work in them, are amazing pieces of technology. They are terrifying in their own way because by virtue of their robot-ness they allow for an efficiency of storage and retrieval in ways that aren't possible for humans and our puny meat-y limbs.

It is a system that humans, unaided by robots and sensors and algorithms, simply don't understand. I have friends who've visited some of the warehouses and they report that there are lasers on the ceilings whose purpose is simply to direct humans to move items from one shelf to another.

Which seems sort of grim and, well, in-human on the face of it. That is the conventional thinking until you actually buy something from Amazon and have that thing show up the next day.

There are some very real costs associated with that piece of future magic that may dictate its longterm viability but, all things being equal, I have never met anyone who wants to go back.

Short of promoting a particularly noxious brand of lifestyle porn around the idea of artisanal warehousing

this is the future because it makes possible a kind of expectation around access and delivery.

It's access and delivery to things like books and cat litter today but if we can make it work for those sorts of generally trivial things I am pretty sure we're going to start expecting it for the important stuff.

Because you know, or should know, that this is what people are going to imagine the basements and archives of museums will look like soon. That's going to be very difficult for us but the reality is that people's expectations of what is possible are changing and we would do better to acknowledge that fact and not get stuck being grumpy old men yelling at the sky.

And this is the important bit. The first thing to understand is that this is not, absolutely not, about establishing the primacy of the digital over the analog or vice versa. I happen to believe very strongly that, at the end of the day, our goal is to get people in the building. I say that because I believe that there is something valuable in rubbing up against the the things we collect, in the flesh.

Because if we don't believe that then we have a pretty serious question to answer which is: What's up the building? Really. Is it just a very expensive business perk that we indulge ourselves in, at the expense of everyone else?

The second is that whether it's unwillingness or inability (or both) that prevents us from doing for our collections what Amazon and others have done for retrieval and delivery all we have left are the digital proxies.

More deep breaths.

The good news is that this is okay. This is better than okay. This is presents an opportunity that we've never had before and we have proven, by the work that precedes us, that we are not complete morons so I believe we can make something of this.

The bad news is that we are competing with Tumblr. Not Tumblr the company but the ability to, more easily than ever before, collect and catalog and investigate a subject and to share – to publish and to distribute – that knowledge among a community of peers.

Which sounds an awful lot like classical scholarship to my ears. Even if the subject happens to be exercise treadmills. Or tyre swans.

Call me naive but I thought that we had decided that what was important was measuring people on the rigour and merit of their study and not so much on the subject themselves. We've been bitten by those blinders so many times already that maybe we could just get past them this time?

Because people are going to do this. They are going to build catalogs and registries and pointers to the things in their life and they are going to put them online so that they have... a center of mass around with the rest of their lives can orbit.

But most important of all is that people are going to do this because they have the means at their disposal. We no longer operate in a world where we have any kind of special access to the means of production and no one is ever going to go back to that world, at least not willingly.

Ask yourselves this: Why didn't David Walsh give his collection to one of our museums? I am less concerned with the answer than with the question, in this case. MONA is the far end of the spectrum when we talk about what's possible. David Walsh has, I'm told, more money than the sky but squint your eyes a bit and you see not money but means and desire.

Now look back at the internet.

Because this is what 2012 looks like for museums.

It is most definitely not about Twitter but about the fact that some random person out there on the Internet is building a record of understanding about Roombas that may well rival anything we will ever do ourselves.

Beyond that, we are being forced to accept the fact that our collections are becoming "alive". Or at least they are assuming the plausible illusion of being alive.

We are having to deal with the fact that someone else might be breathing life in to our collections for us or, frankly, despite us. We are having to deal with the fact that it might not even be a person doing it.

And it's going to look weird. A lot weirder than this, probably. But stop, for a moment, and just let this this example settle in.

Imagining the possibilities and the consequences of a robot vacuum cleaner self-powered by an on-board anaerobic digester and set loose on the streets of our major cities to clean up after dogs (or horses or cows) might be a genuinely useful conversation to have. It’s an interesting discussion, either way. It’s what designers do. Why wouldn’t the Cooper-Hewitt want to be the place where that discussion happens?

But we need to have confidence that people are not merely capable but are actively making sense of things, for themselves. And maybe not on our terms. We need to have confidence that our collections can bear the weight.

It's also going to be silly.

Recently we were able to have the Cooper Hewitt collection webpages white-listed for Twitter's new "cards" functionality. "Cards" allow you to include a little bit of extra metadata – a photo or a description – in your webpages which is then displayed, on Twitter, if someone links to that page in a tweet.

This is great. It reinforces the idea that the objects in our collections have a center of gravity around which other stories can orbit. It also means I can say, and do, things like this.

Does everyone know who Purple and Brown are? This is not Purple and Brown. It's tasteful modern ceramic tableware by Eva Zeisel. A classic, by many people's standards.

This is Purple and Brown.

I'm pretty sure you'll never be able to look at those salt and pepper shakers the same way again. Sorry about that. That you'll never be able to not make this association again ought to tell us something, though.

If it makes you feel any better Purple and Brown are produced by Aardman whose credits also include Wallace and Gromit, so these must be "art" and not just silly claymation shorts.

Right?

Meanwhile, it's not as if our own house is in order. Our databases are full of incomplete data and half-told stories that might benefit from some help, or even a little horsing around.

This is probably the most famous chair in the world and we call it "chair #670". I choose to believe that there are more interesting stories about this chair out there. If there aren't this is not the most compelling way to argue for why it's in a museum collection in the first place.

Giving people the means to relate their stories to ours is really just fancy-talk for giving people something to link to. Giving them something that they can use as a reference point for what might be a whole other interpretation than ours, or even just a passing allusion costs us nothing.

It does not undermine our work or our viewpoint and ultimately offers the potential for a richer and more fertile ground to roll around in, if and when we're ready to do that. Other people pointing to our stuff does not somehow mean we confer notability or relevance on their work. We don't have to link back. We do however need to let them link to us.

If nothing else it says to people: We walk among you. We walk with you.

The important part here is giving people not just a way but a thing – out there on the internet – to connect with. Loan items in exhibitions are a good example of one place we actively don't do this.

One of the tiny victories in the alpha version of the new Cooper-Hewitt collections website is calling out that although there might have been 400 objects in an exhibition we will only show six of them. But that's only going to buy a very limited amount of grace time. How long before someone out there, who has nothing to do with museums, starts building websites that pull in data from all the participating museum websites to create an exhibitions site that reflects, well, reality?

I understand that talking about loan items out loud is like the third rail of the museum world but here's another way to think about it: Our sausage making is no one else's problem.

Our inability or unwillingness to acknowledge publicly that a loan object ever existed in our collections past the date that an exhibition closed is insane. Flat. Out. Insane. It doesn't make any sense. Not even a little bit.

How exactly do we rationalize telling the same people who we've asked to come and see these damn things that past a certain date there is no way prove they were ever a part of our history? Especially when we publish books that demonstrate that they were. And if the argument is somehow that books provide museums with a kind of gated access that the web does not, or can not, then we've got some much bigger issues to work through.

I have heard all the reasons why we can't do this. Some of them range from genuinely difficult like the toxic soup of image and reproduction rights to simply stupid like not doing anything at all. Either way, why are we asking visitors to have to think about this stuff at all?

If all we did was make public, on the network, items in an exhibition as an accession number (or artisanal integer) along with some minimal viable metadata like its title and creator(s) then we do not claim that thing as our own but we do claim its transit through our history as our own. If we can't even do that then we not only create a giant vacuum but we invite someone else to fill it.

It happens, too. If you talk to anyone who has worked at Flickr in the past, or present, they can give you reasons a mile long and a mile wide why there are still no decent mobile clients for Flickr. And there are lots of reasons. Most of them legitimate. Many of them are honestly outside of Flickr's control.

That is also no one else's problem. There is, by now, nothing that can justify asking users to make accommodations for Flickr's inability to make sense of mobile. There is also no reason why Instagram should either. Instagram simply walked in to the vacuum that circumstances had created and saw an opportunity and made a billion dollars while Flickr looked on wondering why no one could , or would, feel their pain.

I take no joy in saying that but I think it's a lesson we all ignore at our peril. If we're going to keep telling people that we have all this nice stuff and that its in their interest that we keep it we need to be able to at least prove that it exists.

This, by the way, is the "inflatable chair" from the title of this talk. It's an inflatable Eames pool chair and we dreamt it up in the design workshop I mentioned at the top of the talk. It's also a nice visual device for suggesting that even beyond loan objects maybe we, and especially we the Cooper-Hewitt, should start to include the things that we sell in our shops in our collections.

Consider the following quote:

It relies on the assumption that physical possession of an object as a requirement for an acquisition is no longer necessary, and therefore it sets curators free to tag the world and acknowledge things that “cannot be had”—because they are too big (buildings, Boeing 747’s, satellites), or because they are in the air and belong to everybody and to no one, like the @ [symbol] ...

That's Paola Antonelli talking about MoMA acquiring the "@" symbol in to their collection. That's one of our own talking, essentially, about the museum engaging in a kind of fan fiction at a level of entire cultures.

I had a very hard time with this when it was first announced and while I might still quibble with some of rhetoric that she uses to discuss the acquisition on measure I've mostly come around to it. I think.

If nothing else I think it forces us to take a cold hard look at the relationship between the motive and the mechanics of how we collect, of how we measure, things. If we accept that the measure of a thing is the merits of our argument and of reaching people with the craft of our story-telling rather than the pomp and ceremony surrounding its production then things are about to get very interesting.

This image is from a presentation I did earlier in the year about a project of mine called the "wanderdrone". I'm not going to talk about the project very much except to say that it involved a drone and a map and a lot of wandering around.

The wandering is just a trick of the eye because the drone itself always remains at a fixed point in the center of the screen while the map underneath it pans from side to side and up and down with the drone rotating to complete the illusion. Occasionally the map will change zoom levels.

Like I said, it doesn't do much but I love this piece. I love it because although I've been making maps for a long time now it had never occurred to me to use the idea of a dumber than dumb application that literally just wanders around the entire planet as a better way to showcase the art and craft of cartography and the beauty of the landscape.

Around the same time that I was working on the wanderdrone Google released version two of the Google Art Project with even more of their magic zoom-y zoom gigapixel images. The panel on the right, there, is actually one of those zoomed-in views. It's a painting by Manet not, as you might think from looking at it, an aerial view of the Australian outback.

But here's the thing: This is not a work by Manet. It doesn't exist. This never existed, at least not until Google came along. This is new work. It's beautiful in its own way but it's important to recognize that before these canvases were gigapixel-ed no one had ever seen this, not even the painter himself. Our little meat-y eyeballs just don't work that well.

If all the technology and effort behind the projects and tools like gigapixel cameras is just to look at cracked paint then maybe we need to ask ourselves whether or not it's a bit of an indulgence. On the other hand, it's also suggests a pretty fabulous opportunity to offer an entire novel way to spend time with our collections. A kind of robot fan fiction, if you'll excuse the further abuse of an already abused phrase.

On bad days, museums are exceptionally greedy of people's time and assume that the only measure of success is to gobble up an entire afternoon of someone's time hoping they will leave in a daze of cultural shock and awe.

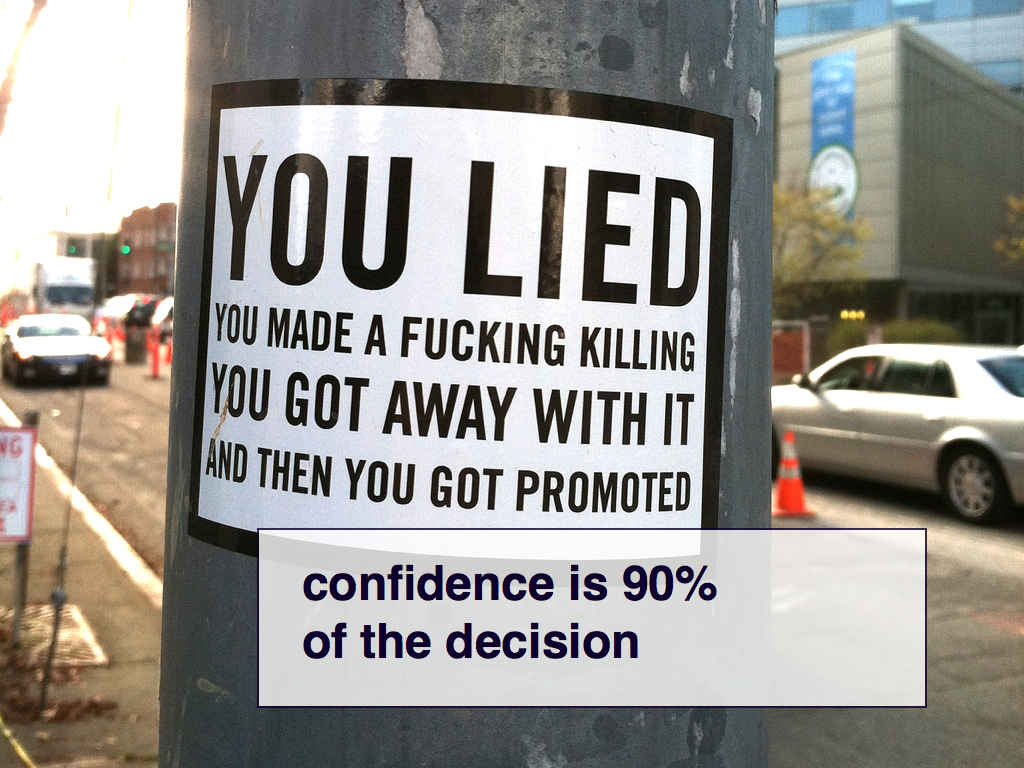

We still think of everything in units of publication whether it's an exhibition or an event or a book. Ever since the Art Project launched the museum community has held regular therapy sessions (disguised as panels) at one conference or another and I hang my head a little lower each time I hear people discuss the Art Project as though it were just another publishing platform.

Because we all know that world is over and gone and never coming back, right? We can no longer hide behind the means of production as any useful measure of notability or critical relevance. All publishing a book means, these days, is that you know print-on-demand services exist and that you're probably thinking about the economics of book publishing a little more critically.

I realize that it may sound like I am calling for yet another Year Zero; that we smash the clocks and restart everything anew, Paris Commune style. I'm not. I find that sort of rhetoric a bit tiresome, honestly. But I do want to know why there aren't more wanderdrones for our collections, yet. Not necessarily always on but always politely present, always willing to answer out there on the network, acting like old skool snakes and ladders in and out of all this amazing stuff we've been charged with keeping safe.

Also, that bit over there on the right: Not an abstract expressionist painting. It's the Aral Sea as seen from a satellite.

What follows is a last minute addition. It first appeared when I did this talk in Melbourne. It's a bit wooly and open-ended because I'm not sure what I think about it all but it feels like there's something here...

For those of you who don't automatically recognize this photo it's not just a stuffed Koala but "Sam" the Koala from the 2009 bushfires in the (Australian) state of Victoria. Sam, when he was discovered, was quite badly burned and eventually nursed back to health under the loving gaze of the media and the public. Still Sam died about a year of chlamydia which is not uncommon among Koalas.

Sam now lives in the Melbourne Museum, complete with a replica of his bandages that its worth noting it no longer needed by the time he died. Quite a lot of people were seriously wigged out by seeing Sam stuffed and put on display. Because, you know, it's actually Sam. As opposed to all the other stuffed animals on display in the Wild

exhibition, next door. And if that weren't weird enough he also lives downstairs from one of at least three separate representations of the famous race horse Phar Lap.

I confess I knew nothing about Phar Lap, or his cultural significance, before coming to Australia and New Zealand.

The first time I saw him was in Wellington where the skeleton lives. At the time I also learned that the heart is the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra. Which is kind of weird but hardly uncharted territory for museum collections. Ely Wallis told me about the ongoing debate wherein the natural history scholars routinely drive the humanities scholars to distraction by labeling Phar Lap as nothing more than a common horse. That was sort of funny.

I was not, however, quite ready to meet Phar Lap again in Melbourne. Or rather the hide of Phar Lap stretched over a wire frame instead of a replica of the skeleton. Apparently both the skeleton and the hide have been shown side by side which is ... a bit unsettling, really.

Is the real skeleton just a glorified wire frame? Is the hide a very elaborate halloween costume or it is simply a hoodie? Were they, as I've been urging for the last hour, holding hands? One of the other products to be included in the near future product catalog, we made in Detroit, is an at-home kit for making old-fashioned death masks of your pets which no longers seems like much of a stretch anymore.

So, while it's still too soon for me to know what I think about Sam and Phar Lap, or to know what I think I am looking at when confronted with their many, very literal, representations I think they are worth keeping in mind as we work through what it means for the things we collect to exist on the network.

Note: I had not yet read either James Bridle's essay on trap streets or Dan Catt's blog post on flip-flopping digital and analog artifacts when I gave this talk but if I had I almost certainly would have mentioned them. Both are absolutely worth reading. I would also have mentioned Joanne McNeil's blog post on the junk ships of Alibaba, if she hadn't written it two days after I finished writing up this talk.

In closing, I want to touch on and leave you with the question of baselines. I want to leave you with a tangent that isn't really.

I live in New York City now. I was there during hurricane Sandy but we live the part of Brooklyn that weathered the storm without any troubles. Lots of people had it very very bad and we were very very lucky. This is pretty much what my experience of the storm was like: Sitting at home watching it all unfold on the internet, more or less in real-time, until the cable company went dark. Even then, though, the cellular networks stayed open all night in our part of town.

I also grew up in Quebec and I have lived through my share of province-wide power outages, in the dead of winter, so I am keenly aware that electricity is the weak link in everything I've been talking about.

There is a general sense that, in 2012, nothing will work as we know and expect it to if the power goes out. I tend to agree with that sentiment and maybe it's okay to feel that way. And by okay I mean that there have always existed baselines that we as a community and a society have pledged to preserve; that it we ever stop fulfilling that mandate it will mean everything's gone well and truly wrong.

Plumbing, for instance. Try to imagine how long life as normal

would last if the bad stuff didn't go away when you flushed the toilet. That's a scenario that sharpens the mind. Perhaps electricity – keeping the lights and the servers on – has already crossed the Rubicon but I just don't remember that conversation being had in the public eye.

It's a conversation we should have if only so that we can know and recognize the consequence of what embracing the network entails.

Thank you.

This blog post is full of links.

#timepixels